'I realised I had autism when my children were diagnosed'

BBC

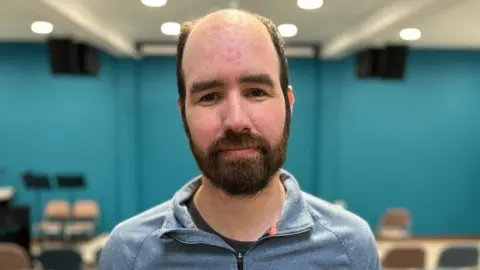

BBCAs a child, William Butchart enjoyed neatly lining up building blocks according to colour - something he now sees as a "stereotype" of autism.

The things he found to be challenging, and often distressing, about the condition were very different.

William felt unable to follow social "norms" - he struggled to make friendships or understand "banter".

He also experienced a number of sensory issues. Certain textures and foods were unbearable and sudden, loud noises could overwhelm him with fear.

But as he got older, William says he learned to "blend into the background", effectively masking his autistic behaviours.

That was, until both his children were diagnosed with the condition.

William's son, who is non-verbal, was two when he was diagnosed and his daughter was only identified as autistic after she had a mental health crisis at age 13.

Learning more about his children's condition, church minister William realised they all shared problems with noise and had very restricted diets. He and his son eat only "beige" foods.

The realisation led him to question struggles he had lived with for decades.

"I couldn't leave it to just how I feel – I needed somebody to actually assess it," he said.

"Once I started to learn what autism actually was, it began to chime more and more with me."

Autism is a lifelong developmental condition which affects how people communicate and interact with the world.

Some find it difficult to understand how others think or feel, while others experience sensory issues - meaning bright lights or loud noises can be overwhelming, stressful or uncomfortable.

There are at least 56,000 autistic people in Scotland, both children and adults, plus an estimated 225,000 family members and carers.

According to the Scottish government, there has been a "significant increase in referrals" - which is putting pressure on an already-stretched NHS.

Autism 'stereotypes'

Last September, William received his own diagnosis through a private clinic.

The 41-year-old from Ellon, Aberdeenshire, had initially pursued an investigation through the NHS but found the process difficult and knew the wait was long.

"You have to fight with your GP," he said. "You have to prove you might be autistic before you can even get on the pathway.

"I know people that have gone to their GP and been told you just have social anxiety disorder, but what's causing the social anxiety disorder?

"I decided, in the end, I had the opportunity to go private so I did."

William said his diagnosis came with a sense of relief.

It answered a lot of questions and helped him identify that outside factors, and not people, were often the source of his frustrations.

But working out what to do with the information was another hurdle. "You've kind of got to work it out for yourself," he said.

It took William two weeks before he felt able to tell people outside close family about his condition.

He was particularly worried about telling colleagues in his church - but found that people were very positive, and in some cases, unsurprised.

William then took part in a six-week support group called Embrace Autism - which is funded by the Scottish government and run by the think tank Autistic Knowledge Development.

Here, he was able to reflect on how all of his life experiences - including the most difficult - had shaped him into a more caring person.

"There's such a wide range of people that are autistic, from people who are in professions to people who are finding all that a real challenge," he said.

"There's a stereotype that autistic people don't feel empathy - that's a lot of nonsense. Some might not - others have the opposite problem, there's too much."

"I learned how to read people, I learned how to manage how I was presenting.

"But I also learned that I don't want to make people feel how I was made to feel."

In Scotland, more adults are seeking an autism diagnosis later in life because of better awareness of neurodiversity, according to the National Autistic Society Scotland.

The charity said people often report feeling "broken" before diagnosis, and that it is important for autistic people to understand both their challenges and strengths.

But it said some people wait years to be seen by the NHS - and in some parts of Scotland, people cannot get a diagnosis at all.

It wants the Scottish government to make more funding available to adult autism diagnosis.

But waiting lists are not publicly available in Scotland so it is not yet possible to understand the scale of the problem.

In England, where the statistics are published, the number of adults waiting for treatment has risen from 9,705 in 2019 to 78,638 last year.

Dr Chris Williams, vice chair of the Royal College of General Practitioners (RCGP) Scotland, said that GPs were not unwilling to refer patients who would benefit from support - but that the criteria for referrals was very strict.

He said it would be helpful if the public was better informed about this criteria - and how there is no treatment or 'cure' for autism, which is not an illness.

Lengthy waits, he says, has led to more people seeking a diagnosis in the private sector.

The Scottish government has said that people are waiting too long for a diagnosis through the NHS but that it is working to improve access.

Mental Wellbeing Minister Maree Todd told BBC Scotland News: "A combination of factors, including a significant increase in referrals, means that some people are waiting longer than they should for a diagnosis.

"We invest £1m a year to provide community and support to autistic adults, including the Embrace Autism programme.

"Formal diagnosis is not required to access the support provided and we know that 78% of autistic adults supported have reported improved wellbeing as a result."