Creatine: The bodybuilding supplement that boosts brainpower

Alamy

AlamyCreatine is often taken by people looking to build muscle. Now scientists are investigating the effects this chemical has on our cognition and mood.

If you've heard of creatine, it's likely because it's one of the most well-researched supplements. It has long been associated with improved endurance and performance during exercise, and is commonly taken in the form of creatine monohydrate by bodybuilders. But the compound isn't just potentially useful to those looking to expand their muscles.

Creatine is a vital chemical ingredient in our bodies, where it is produced naturally within the liver, kidneys and pancreas and stored in our muscles and brains. The creatine we produce typically isn't enough for our total requirements on its own, so most people also rely on sources in their diet – certain foods, such as meat and oily fish, are rich in this nutrient.

Creatine helps to manage the energy available to our cells and tissues, and there's emerging evidence that some people might benefit from creatine supplementation.

From reducing post-viral fatigue to improving cognitive function in people who are stressed, and even boosting memory, creatine supplements may provide some people with a significant cognitive boost. It's also been speculated that creatine might help to alleviate symptoms in patients with Alzheimer's disease and improve mood. So, are you getting enough creatine? And when is it a good idea to take a supplement?

The birth of creatine research

The benefits of creatine supplementation were first discovered in the 1970s by the late Roger Harris, a professor from Aberystwyth University in Wales. Creatine has since become well established in the sporting world, with a wealth of research behind it linking it to improvements in our physical function.

But over the last two decades, studies have been starting to reveal other potential health benefits of creatine supplements. One of the biggest areas of research is cognitive function, given that creatine plays a role in neogenesis – the formation of new neurons in the brain.

When Ali Gordjinejad started to notice studies linking creatine supplementation to working and short-term memory in sleep-deprived people, he saw that they were suggesting that a person had to take creatine for weeks or months to see any benefits.

"It was assumed that the body's uptake of creatine cells is marginal, therefore it wouldn't work for only one night of sleep deprivation – until we did our study," says Gordjinejad, a research scientist at the Forschungszentrum Jülich research centre, in Germany.

Getty Images

Getty ImagesGordjinejad decided to test the effects of one dose of creatine on cognitive performance following only one night of sleep deprivation. He recruited 15 people, and gave them either a creatine supplement or a placebo at 6pm. He tested their cognitive performance – including reaction times and short-term memories – every two-and-a-half hours until 9am.

Gordjinejad found that processing speed was much faster in the creatine group compared with the placebo group. Gordjinejad doesn't know exactly why, but he suspects it's because the sleep deprivation and cognitive tasks put participants' neurons under stress, and this triggers the body to take in more creatine.

"If the energy demand is high from cells, then phosphocreatine (which provides energy for short bursts of effort) comes in and acts like an energy reservoir," says Gordjinejad, who explains that dietary creatine can help this reserve to fill up again.

If cells need a lot of energy for a short period of time, phosphocreatine can come in and act as an energy reserve, Gordjinejad explains.

Though Gordjinejad's study was small, he believes his findings show that creatine could potentially help to overcome the negative effects of sleep deprivation – but only in the short-term, until you sleep.

However, the participants in Gordjinejad's study took 10 times the recommended daily dose of creatine – they had 35g, which is around half a glass full of the powdered supplement. (Do not try this at home.) This dose, Gordjinejad says, would pose a risk to people with kidney problems, and in the general population it could cause stomach pains.

Gordjinejad plans to conduct a similar trial where he gives participants a smaller dose. He hopes that, in the future, creatine could be used in this way by people who have an unexpected prolonged period of being awake, such as emergency service workers, or students doing their exams.

However, Terry McMorris, professor emeritus at the University of Chichester, carried out a review of 15 studies in 2024, and found that research so far fails to support the theory that creatine supplements can improve cognitive function.

Getty Images

Getty ImagesHowever, McMorris says this may be because studies he looked at used various different creatine supplement regimens. Also, he explains that many studies relied on outdated cognition tests. "Some date back 1930s – they're too easy, we don't push people enough," he says.

But while McMorris says there's not enough evidence to draw any conclusions, he believes it's an area worth more research.

Cognitive performance aside

Studies are showing a range of other potential health benefits of creatine, including stopping the progress of tumours in some animal studies, and improving menopause symptoms. One reason for this may be that creatine could have a protective antioxidant effect that can help our bodies to weather the effects of stressors.

One recent study involving 25,000 people found that, among participants aged 52 and above, for those who had the highest levels of creatine in their diets, each additional 0.09g of creatine over a two-day average was linked to a 14% reduction in cancer risk.

Creatine may also have benefits to our mental health. In one study, people with depression were given creatine powder alongside a course of cognitive behavioural therapy (CBT). The researchers found that, over eight weeks, their symptoms improved more than those who had CBT without creatine.

"One reason creatine might help people with depression is that it's used to a significant degree for energy production and usage in the brain," says Douglas Kalman, adjunct professor of graduate sports nutrition at Florida International University. If creatine levels are low, this affects energy production in the brain, but also the levels of neurotransmitters – chemical signals that allow nerve cells to communicate with each other – he says. This, in turn, can affect a person's mood.

This finding may be especially important for vegans, says Sergej Ostojic, professor of nutrition at the University of Agder in Norway. According to some research, this group is at higher risk of depression. Creatine might be at play here, he adds, as vegans have been found to have less creatine in their muscles than those with omnivorous diets.

There is even some research suggesting that creatine could even help with chronic conditions. In 2023, Ostojic and colleagues from the University of Novi Sad, Serbia, tested the effects of creatine supplements in 19 patients with long Covid.

The researchers gave 4g of creatine to half the participants, and a placebo to the other half. Then they monitored their symptoms, and the levels of creatine in their brain and muscles. After six months, the team found that those who received extra creatine had improved symptoms, including less brain fog and concentration difficulties. The more severe the disease, the lower levels of creatine in their bodies had been at the beginning of the study.

"The hypothesis was that the brain, under the stress of long Covid, depletes levels of creatine, which is a critical energy-supplying substance," Ostojic says.

While creatine isn't a cure for long Covid, Ostojic concludes, it could provide some benefits. But there's more work to do; he wants to better understand potential gender differences at play when it comes to creatine and conditions such as long Covid.

Women are more likely to develop long Covid than men and have a different creatine metabolism. Due to fluctuations in hormones, it's thought that the transport, bioavailability and synthesis of creatine in the body can change throughout a woman's life.

Ostojic adds that women tend to lose more creatine through their urine and have lower levels of muscle mass compared to men. Since this is where most creatine is stored, it makes sense that women would have less creatine overall. "My preliminary feeling is that women with long Covid might respond better to creatine supplementation [than men]," he says.

The lifecycle

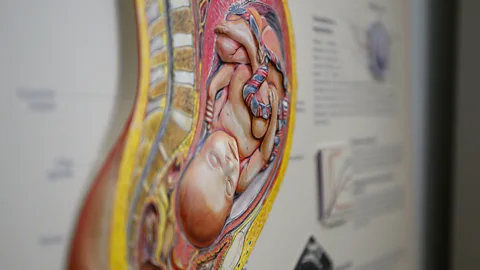

One shift in the way creatine has been researched recently is that its role is now being looked at through a person's entire lifecycle, says Kalman. For example, there's a growing body of research showing the important roles creatine may play from conception to a baby's first few years of life.

The cells and tissues in our bodies use creatine as an energy source at every stage of reproduction, says Stacey Ellery, an NHMRC Peter Doherty early career research fellow at Monash University Australia. This incudes sperm motility, uterine and placental development, as well as foetal growth and breastmilk.

Creatine may also have an important role in reducing the damage caused by a lack of oxygen, says Ellery, such as to foetuses during birth or in the womb. A lack of oxygen can restrict the ability of cells to generate sufficient energy in crucial tissues, such as the placenta and foetal brain, which can stunt their growth or impact their long-term health, she explains. But in the very short term, creatine can allow cells to release energy without needing oxygen.

"A creatine supplement can boost the creatine available to cells for energy production during oxygen deprivation," says Ellery. "Consider it like charging a spare battery for a power outage. Keeping the cells energised lowers the risk of serious harm to the developing baby."

Getty Images

Getty ImagesAnd creatine may be critical in complicated pregnancies. Ellery has seen in her research how, in pregnant women with the potentially life-threatening condition pre-eclampsia, for example, the placenta can adapt to increase creatine levels in the mother's body. However, the safety of supplementing with creatine during pregnancy has not been studied directly yet in humans and it’s important to discuss any supplements with your doctor first.

More creatine seems to be sent from the mother to the baby during long and difficult labours, says Ellery, and lower levels of creatine in mothers' blood during the final months of pregnancy have been linked to a higher incidence of stillbirth, preterm birth, smaller babies and admission to intensive care. However, it is unclear why this is the case, or whether supplementing with creatine would be helpful.

While research in this area is in the early stages, Ostojic recently published the first calculations of recommended daily creatine intake for infants up to 12 months old. He estimated that exclusively breastfed infants require 7 mg per day up to six months old, then 8.4 mg per day for infants aged 7-12 months. He says more data is needed.

And at the other end of the lifecycle, creatine may also help with our muscle health as people develop sarcopenia, an age-related condition that reduces muscle strength and mass. "As people get older, they have less muscle tone," Kalman says. "And studies have shown that creatine could help reduce the amount of sarcopenia."

The risks of taking creatine

Though some people might benefit from supplementing with creatine, it can come with some side-effects, including water retention, muscle cramping and nausea. Creatine also isn't suitable for some people, including those with kidney or liver problems or who are taking certain medications. While creatine is thought to be broadly safe and well-tolerated, there have been rare cases of major adverse events associated with the supplement, such as liver failure.

Are we getting enough creatine?

There is emerging evidence that most women eating a Western diet don't eat enough creatine-rich foods, says Ellery. A recent study found that six out of 10 women didn't consume the daily creatine intake recommended by researchers (13mg per kg body mass per day) and nearly one fifth of pregnant women consumed no creatine at all.

Preliminary studies suggest adults require around 1g of creatine per day. Early data from population studies suggests that depression, cardiometabolic disorders and cancer are more prevalent in people who consume less than 1g of creatine per day. However, there are no official public health recommendations regarding daily creatine intake.

Most people are able to get creatine from their diets, Ostojic says, but vegans may be at risk of not getting enough.

Creatine is a naturally occurring compound in the body, which means it isn't defined as "essential". Essential nutrients can't be synthesised by the body and, therefore, must be supplied from foods. However, some researchers, including Ostojic, argue that creatine should be categorised as semi-essential, as it appears we can't synthesise enough.

"A couple of studies suggest people who don't get any creatine from food have lower levels of creatine in their muscles, suggesting they're not able get it to the optimum point," says Ostojic.

Creatine is not a silver bullet, he says, but argues it should be evaluated properly and evidence-based guidance should given to the population.

Despite being the focus of many studies – and lacking in many people's diets – research on creatine's health benefits throughout our lives is still in its early stages.

Researchers including Ellery are hopeful, though, that the rising academic interest in creatine will eventually translate into public health interest, so that we know which population groups would benefit from creatine supplements.

* All content within this column is provided for general information only and should not be treated as a substitute for the medical advice of your own doctor or any other health care professional. The BBC is not responsible or liable for any diagnosis made by a user based on the content of this site. The BBC is not liable for the contents of any external internet sites listed, nor does it endorse any commercial product or service mentioned or advised on any of the sites. Always consult your own GP if you're in any way concerned about your health.

--

For trusted insights into better health and wellbeing rooted in science, sign up to the Health Fix newsletter, while The Essential List delivers a handpicked selection of features and insights.