A border split my family's language. Now I'm bringing it back

Prashanti Aswani

Prashanti AswaniSanjana Bhambhani's ancestors fled their homeland during India's Partition – and her family gradually lost their mother tongue. Can she now reclaim it?

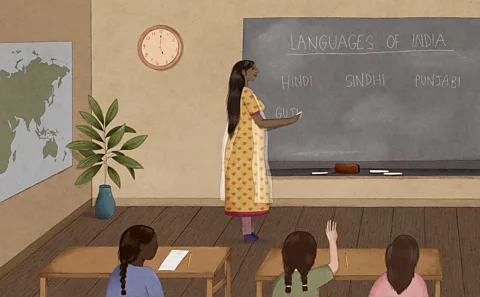

When I was around eight years old, a teacher at my elementary school in New Delhi, India, asked us which languages our families spoke at home. India is one of the most linguistically-diverse countries in the world, with estimates suggesting that we collectively speak between 122 and 456 languages. In New Delhi, as in several other big Indian cities, people tend to use at least two languages daily: the one commonly spoken at work, in school or in government offices (as Hindi is in Delhi), and a regional language which connects people to their ancestral culture and is spoken within the family.

Of the Indian languages, I grew up only speaking Hindi. I had no idea what my family's second, regional language was. When I asked my father, his answer puzzled me.

"Sindhi," he said.

I had never heard of this language. My father explained that the region where Sindhi is predominantly spoken – namely Sindh – is not in India but in Pakistan, our neighbouring country. How did my family come to lose our ancestral tongue? Why, unlike other Indian families, did we no longer speak our regional language?

The answer lies in an event that not only disrupted my family's history but reshaped South Asia: the Partition of British India.

In 1947, as the British left India after almost two centuries of colonial presence, they drew what's known as the "Radcliffe Line", splitting the country in two: India (with a Hindu majority) and Pakistan (with a Muslim majority). During this division, Sikhs, Muslims and Hindus fled their homes, triggering one of the largest forced migrations in history. Between 14.5 and 17.9 million people escaped for their lives in the midst of immense violence and turmoil. Among them was my grandmother.

My grandmother is from Sindh which, before Partition, was a more religiously and culturally mixed province where both Hindus and Muslims lived, with a Muslim majority. Sindhi was the most commonly spoken regional language. As the country was divided, Sindh ended up in Pakistan, and its Hindu minority – including my grandmother and her family – escaped to India, fearing the persecution of Hindus.

And so, Sindh lost a majority of its Hindu community, and Hindus from Sindh – many of whom had fought for India's freedom from colonial rule – lost their home, the place where their mother tongue, Sindhi, is spoken.

At the age of 14, my grandmother left everything behind: the neighbourhood she grew up in, the streets she walked, the relatives and friends she held dear.

"We didn't have so much as a teacup and saucer to our names," she told me – two important symbols of community and bonding in our tea-drinking culture.

Prashanti Aswani

Prashanti AswaniThere was one remnant of her childhood my grandmother could bring across the border: her language, Sindhi.

One of the most intriguing things about Sindhi is that it unites linguistic features of two countries that are not just divided, but politically hostile towards one another: India and Pakistan.

Sindhi is derived from a dialect of the Prakrit languages which are precursors to Hindi, India's most spoken language. But the majority of Sindhi literature is found in a modified Perso-Arabic script. In a different modification, the Perso-Arabic script is the script of Urdu, Pakistan's national language.

When my grandmother left her home region, she carried this language, symbolic of her culturally-mixed upbringing, with her. However, arriving in a new India, she had to master the dominant language of her new state, Delhi, which was Hindi. It's the language in which I refer to my grandmother today, calling her दादी (Dadi).

Other Sindhis generally adopted the language of the states where they found refuge as well, especially when conversing outside the family. And so Sindhi began to fade among younger generations. In my family, as in many others, once it was lost, it became hard to revive.

Sindhi is quite distinct even from some languages in neighbouring Pakistani and Indian states. For example, it uses implosive sounds, which are pronounced with an indrawn breath. Vimmi Sadarangani, an associate professor of Sindhi at Tolani College of Arts and Science in Gandhidham, India, mentions four in particular: ɓ, ɗ, ɠ and ʄ. Implosives are hard to get right, since they're uncommon in other languages. Sindhi also has five nasal sounds retained from Sanskrit that don't exist and are not used in modern Hindi; they are hard to learn if you didn't grow up using them. You can listen to this audio recording and try it yourself.

Sadarangani explains that without pronouncing these sounds correctly, every other part of mastering Sindhi, including writing it, becomes difficult.

Indian-American entrepreneur Kiran Thadhani, whose grandparents fled Sindh for Ahmedabad, India during Partition, is among those trying to reconnect with the language. She was born in the US, now lives in London in the UK, and is taking classes in Sindhi. But she struggles with pronunciation.

"I always get corrected in my language classes where it's like, 'Say it again', and I'm like, 'Oh dear, I don't know, it's not coming out right!'" says Thadhani.

Some words feel right coming out of the mouth, she says. She knows how to pronounce the words for garlic and onion, for instance, partly because food is such a big part of her family discussions. But there are other words that are harder for her, and never sound quite native. For example, she pronounces the word "guɗi", meaning doll, with a softer, more Americanised "ɗ".

According to Thadhani's parents, though, she spoke her very first words in Sindhi.

"When I started school in the US, there were times when I accidentally blurted something out in Sindhi," says Thadhani. But in the white-majority suburb of Atlanta that she lived in, she felt pressure to tuck away her differences to fit in: one of them being her "Sindhyat" (Sindhi identity).

"Now I have this really mixed relationship with my first language," says Thadhani. To this day, though, she finds it easier to express her deepest feelings in Sindhi. "I don't even have all the words anymore but some of the earliest, youngest feelings that I have – I can't always get there in English but I could get there in Sindhi," she explains.

I've been introduced to a range of Sindhi words and expressions that I find endlessly fascinating through conversations for this article. The word "aɠopoi", which I learned from writer and oral historian Saaz Aggarwal, means "while you’re doing that, might as well get this done too". A handy term that's also representative of the resourceful reputation of the Sindhi community.

This begs the question: if Sindhi is so culturally important, why is it struggling to survive in India?

There were, in fact, early efforts by Sindhi speakers to ensure the language was taught and used in the new India. But one fundamental problem, according to scholars, was that people disagreed over the future of the script of this cross-border language.

In her 2022 article, Language without a Land, Uttara Shahani, a scholar of South Asian history at Oxford University's Refugee Studies Centre, explains that conflict. Among the literary class, some wanted to continue writing Sindhi in the Perso-Arabic script, so that new generations in India could read classic Sindhi literature and speakers in Pakistan could read Sindhi works written in India. This cohort wanted to maintain a connection with the region of Sindh, despite the division.

Others wanted to use the Devanagari script – the one that is used for writing Hindi – because it was understood by many in India. Further, the modified Perso-Arabic script was associated with Muslims, and this cohort wanted to assimilate into the new India as Hindus.

"This conflict is never really resolved," says Shahani.

Today, Sindhi in its spoken form on the Indian side of the border sounds increasingly different to that on the Pakistani side, with some sounds being influenced by Hindi and losing their Arabic pronunciations, Sadarangani says. In her view, truly mastering the language means learning both the Perso-Arabic and Devanagari scripts. "Perso-Arabic Sindhi is also needed to keep the relations with Sindh alive," she says.

It would be hard for me, as an Indian national, to visit the province of Sindh in Pakistan, see my family's ancestral home for myself, and learn more about how the language is faring there today, due to political animosity.

However, young Sindhis like me on both sides of the border are finding other ways to connect, including in countries like the US and the UK to which both Muslim and Hindu Sindhis migrated.

Faraz Ahmed Khokhar is from a Muslim Sindhi family in Pakistan. He lived in Hyderabad, a city in Sindh, till the age of nine and then moved to London with his family. There he co-founded the Sindhi Youth Club. In an ironic twist, he has connected with more Indian Sindhis on British soil than while he was in Pakistan just across the border from India.

"When I was in Pakistan… I didn't have any interaction with Indian Sindhis," he says. "In countries in the West, where it's a bit more diverse and open, you end up mingling, finding friends regardless of where they've come from." The Sindhi Youth Club has both Indian and Pakistani Sindhi members.

Though Sindhi is taught in Sindh's government schools, Khokhar says it is facing some challenges in Pakistan, too. He tells me that Sindhi families in Pakistan are beginning to less frequently speak their regional language at home, instead using the more widely spoken Urdu. The language is competing in urban centres with Urdu, and increasingly, English.

In an effort to preserve the language within his family, Khokhar's parents would tell him off if he spoke to his two younger siblings in English instead of Sindhi at home.

"And I'm glad they did that," he says, because it allows him to speak to people when he goes back to Pakistan, especially in towns and villages where Sindhi is still the main language. "If I didn't know Sindhi as well as I do now… when I travel back to Sindh… I would have been limited to the urban centres."

Prashanti Aswani

Prashanti AswaniOn the Indian side of the border, the decline of Sindhi occurred in part since post-Partition India was organised into states along linguistic borders – those living in Gujarat speak Gujarati and those in Punjab speak Punjabi – and in that system, Sindhi did not have a place of its own.

Hindu Sindhi speakers in states like Rajasthan and Gujarat faced another problem, says Indian author Rita Kothari in her book, The Burden of Refuge: Sindhi Hindus of Gujarat. Although they were Hindu, their Muslim-influenced heritage raised suspicions in the new India, where religious tensions were high. They were coming from a Muslim-majority province, wrote in a Perso-Arabic script and ate non-vegetarian food, which brought their "Hindu-ness" into question.

And then there is the stereotyping of Sindhis, who are known as a mercantile community. In her book, Kothari notes that Sindhis settling in Gujarat's urban centres and built businesses with low margins and no religious or other inhibitions, working odd hours to survive. This undercut local businesses. The resentment against Sindhis is evident in sayings like one that compares us with snakes; one both Thadani and I, living in different parts of the world, have heard this platitude.

A sense of alienation and lack of a home for the Sindhi language was felt when India adopted its constitution in 1950 and listed 14 official languages, of which Sindhi was not one.

Later, Sindhis in India did manage to successfully campaign for their language to be added to that list. But by then, the language had already started to fade.

Today, Sindh is named in the Indian national anthem, which I sang every morning in school without recognising its significance to my identity.

When I think back to the day I was asked to bring the name of my family's mother tongue to school, I remember being allowed to add Sindhi to a list titled Languages of India. A relief, given I was anxious about asking my teacher for permission to add a language from a region now in Pakistan. My anxiety, unbeknownst to me at the time, echoed decades of political debate around the language, its speakers, and their rightful place in India.

Sindhi speakers have also found a new community online, including those who, like me, never learned the language, but would like to as adults. Khokhar says he watches Sindhi videos online and enjoys social media posts and music produced by Pakistani and Indian Sindhis alike.

"You'll often find comments from Sindhis across the border in Sindh commenting very positively and loving the songs [released by Indian Sindhi singers]," says Shahani.

Photo courtesy of Savitri Chadha

Photo courtesy of Savitri ChadhaSindhi cuisine is also one way our community retains a connection with the language.

A popular dish, Sindhi writer Saaz Aggarwal says, is saee bhaji: a combination of dal, spinach, other greens and vegetables, cooked together with tomatoes and spices that are blended into a broth, to be eaten with rice and papad.

"It's awfully healthy and I hated it when I was a kid," she says. She was surprised to find that her kids loved when she cooked it for them growing up. "Saee bhaji is an icon of Sindhi culture!"

She also mentioned Sindhi kadhi which I recall as the dish my grandmother was known for cooking. It's a tangy chickpea flour curry made of vegetables and tamarind juice, that is different from curries found in other communities. Just the thought takes me back to my grandparents' dining room, eating the dish as they chatted with my father in their mother tongue.

At the time, the only Sindhi phrase I recall learning was gute vaaree bhaakee. It means tight hug; a phrase I would use as I threw my arms around my parents and grandparents. While I was researching this article, my father told me I've been saying it incorrectly for the last 10 years, so working on my pronunciation might be my first step in reconnecting with my language. I recently enrolled in a Sindhi language learning course. If I practice enough, who knows, maybe one day I'll be able to re-ignite the use of Sindhi in our family.

Six days after I enrolled in Sindhi classes, my grandmother passed away. I dedicate this article to Prema Bhambhani. who carried an entire language across a border and preserved enough of its memory for me to reconnect with it today.

--

If you liked this story, sign up for The Essential List newsletter – a handpicked selection of features, videos and can't-miss news, delivered to your inbox twice a week.