The lost ancient practice of communal sleep

Getty Images

Getty ImagesUntil the mid-19th Century, it was completely normal to share a bed with friends, colleagues and even total strangers. How did people cope? And why did we stop?

In 1187, a medieval prince slipped into his grand wooden bed, accompanied by a new companion. With a thick mane of auburn hair and strapping frame, Richard the Lionheart was the ultimate macho warrior, renowned for his formidable leadership on the battlefield and knightly conduct. Now he had formed an unexpected friendship with a former enemy – Philip II, who ruled over France from 1180 to 1223.

Initially, the two royals had forged a purely pragmatic alliance. But after spending more time together, eating at the same table and even out of the same dish, they had become close friends. To cement the special relationship between themselves and their two countries, they agreed to a peace treaty – and slept alongside each other, in the same bed.

Despite the modern connotations of two men sharing a bed, at the time this was entirely unremarkable – appearing almost as a casual aside in a contemporary chronicle on the history of England. Long before the expectation of night-time privacy or more recent ideas about manliness, many historians view the two royals' nightly partnership as a sign of trust and brotherhood.

This is the forgotten ancient practice of communal sleep.

For thousands of years, it was completely normal to flop down in bed each night alongside friends, colleagues, relatives – including the entire extended family – or travelling pedlars. When on the road, people routinely found themselves lying next to total strangers. If they were unlucky, this outsider might come with an overwhelming stench, deafening snoring – or worse, a preference for sleeping naked.

Sometimes, "social sleeping" was simply a pragmatic solution to a shortage of beds, which were highly valuable pieces of furniture. But even the nobility actively sought out bedfellows for the unparallelled intimacy of night-time chats in the darkness, as well as warmth and a feeling of security. How did people navigate a night of communal sleeping? And why did this ancient practice stop?

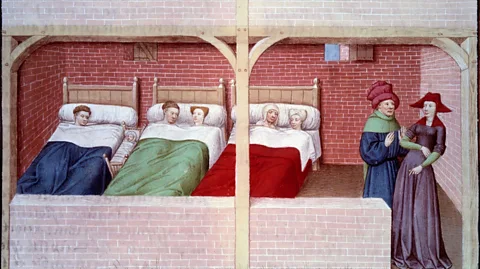

British Library

British LibraryAn ancient tradition

In 2011, a team of archaeologists uncovered an unusually well-preserved layer of prehistoric sediment at Sibudu Cave, South Africa. It contained the fossilised remains of leaves from the forest tree Cryptocarya woodie, which formed the "top sheet" of a foliage mattress constructed in the Stone Age, some 77,000 years ago. As project leader Lyn Wadley speculated at the time, the mattress may have been large enough for a whole family group.

Direct evidence for communal sleep is hard to come by, but it's thought that this practice is truly ancient – in fact, from a historical perspective, the modern preference for sleeping alone and in private is deeply weird. After a brief lapse in antiquity, during which even married members of the upper classes slept alone, the practice made it through the medieval age more or less intact.

However, records of this activity are most abundant in the early modern period – roughly from 1500 to 1800. In this era, bedsharing was extremely common. "For most people, with the exclusion of aristocrats and well-to-do merchants, as well as some members of the landed gentry, it would have been unusual not to have had a bedmate," says Roger Ekirch, a university distinguished professor of history at Virginia Tech, Virginia, and the author of At Day's Close: A History of Nighttime.

Apart from anything else, the vast majority of households had too few beds for private sleeping, says Sasha Handley, a professor of early modern history at the University of Manchester and the author of the book Sleep in Early Modern England.

"Even for the middle and upper classes when they're traveling, which is a lot of the time, they're obviously forced to spend time in lodging houses and inns and taverns, where sharing a bed is a pretty common practice," says Handley.

Around 1590, a small Hertfordshire town became famous for the Great Bed of Ware, acquired for the White Hart Inn. This formidable piece of oak furniture – measuring 2.7m high (9ft), 3.3m wide (11ft) and 3.4m (11ft) deep – features elaborate carvings of lions and satyrs draped in almost theatrical hangings of red and yellow. It would have been available for travellers to share. According to legend, 26 butchers and their wives – a total of 52 people – slept there together in 1689 for a bet.

Sharing a bed did not have the same sexual connotations that it does today. In the medieval era, the Three Wise Men from the Christian bible were often depicted sleeping together – sometimes nude, or even spooning – and experts contend that any suggestion they were engaging in carnal acts would have been absurd.

Getty Images

Getty ImagesSociable sleeping was so desirable, it even transcended the usual barriers of social class. There are numerous historical accounts of people bunking down each night with their inferiors or superiors – such masters and their apprentices, domestic helpers and their employers, or royalty and their subjects. In 1784, a parson wrote in his diary that a visitor had specifically requested to sleep next to his servant. Night-time tussles over blankets and hours of strange bodily noises tended to afford a certain equality that didn't exist outside of the bedroom.

A better night's sleep

One of the most detailed records of communal sleep can be found within the diaries of Samuel Pepys , which provide a portal to life in the 17th Century. Their pages – which he had bound into hardback volumes for posterity – can still be found on the oak shelves of his library in Cambridge, UK to this day. Pepys wrote in them nearly every day for nine years, starting in 1660.

In addition to the minutiae of daily life and frequent lewd descriptions of womanising, the diary records just how often he slept in the same bed as friends, colleagues, and perfect strangers. And they reveal the many nuances of successful – and unsuccessful – bedsharing.

On one occasion in Portsmouth, Pepys went to bed with a doctor who he worked with at the Royal Society in London. In addition to lying "very well and merrily" together, presumably talking late into the night, the doctor had the added advantage of being peculiarly delicious to fleas, who consequently left Pepys alone. (It's also been speculated that the pests didn't like his blood – and perhaps this helped him to avoid catching the plague.)

Tucked up under several layers of blankets, with their nightcaps resting on their heads, Ekirch explains that well-suited bedfellows might exchange stories well into the early morning – perhaps even waking to analyse their dreams between their first and second sleeps. (Learn more about the forgotten medieval habit of biphasic sleep.)

These hours spent chatting in the blackness of night helped to strengthen social bonds and provided a private space to exchange secrets. Handley cites the example of Sarah Hirst, a young gentlewoman and tailor's daughter, who had several favourite sleeping partners for whom she developed great affection. When one of her regular bed mates died, she wrote a poem expressing her grief.

Alamy

AlamyThough she had many beds at her disposal, it's thought that Queen Elizabeth I never slept alone once during her 44-year reign. Each night, she retreated to her bedchamber with one of her trusted attendants, with whom she would unburden herself and dissect the day's activity at court. These women also provided her with protection.

As the historian Anna Whitelock explains in the book The Queen's Bed: An Intimate History of Elizabeth's Court, intrusions from men weren't unheard of – such as in the queen's younger years, when the man who married her stepmother would burst in and slap her on the buttocks. These incidents had the power to be particularly damaging, because she needed to protect her virginity.

A matter of etiquette

In an era where bedsharing was utterly routine and often unavoidable, it was helpful for people to follow proper etiquette to ensure that everyone had a comfortable night's sleep – and avoid fights from breaking out in the night. Bedfellows were expected to avoid talking excessively, respect one another's personal space, and avoid fidgeting.

But things clearly didn't always go to plan.

Late at night on 9 September 1776, two US Founding Fathers – Benjamin Franklin and John Adams – found themselves in the midst of a fierce debate while sharing a room, and a bed, at an inn in New Brunswick. The discussion had started when Adams went to close the window.

"'Oh!’ says Franklin, 'don't shut the window. We shall be suffocated.' I answered [that] I was afraid of the evening air," Adams later recalled in his diary. Franklin thus began a long rant about his new theory of colds, which he believed (correctly) were not caught from cool fresh air, but by recycling old air in a stuffy room. Adams was "so much amused" by this unexpected lecture that he promptly fell asleep.

Such was the problem of dealing with unruly bedfellows that one French phrase book from the early modern era provided English travellers with a few choice words with which to lambast their sleeping companion. The volume, which Ekirch discovered while researching his book, suggested translations for: "you do nothing but kick about", "you pull all the bedclothes", and "you are an ill bedfellow".

Alamy

Alamy"There are lots of quite fun anecdotes I came across where people ranked the quality of their co-sleepers by their ability to tell a good story, or not to snore," says Handley. She cites one example of a disgruntled schoolmaster who compared his bedfellow – a rector – to a pig, after he went to bed drunk and made a "hideous noise".

Pepys had a few run-ins with his bedmates, one of whom he kicked out of bed after they "fell to play with one another", causing him to complain that he had to lay alone all night.

But there were also conventions which aimed to avoid more serious consequences. In most circumstances, it was unusual for unmarried men and women to share a bed with someone outside their own family. When it did happen, there were attempts to minimise the risks.

Ekirch came across one observer's account of the strict arrangement of sleeping positions at an Irish household in the early 19th Century. The eldest daughter aways slept next to the wall farthest from the door, followed by her sisters in descending age order, then the mother, father, and sons, also in age order. Finally, strangers "whether the travelling pedlar or tailor or beggar", would sleep at the end, where they were farthest away from the female family members. This practice was known as “to pig”.

There were also cases where male and female domestic workers were required to sleep together due to a bed shortage. "It was a common belief and source of humour – at least for those whose servants were not involved – that this sometimes resulted in pregnancies," says Ekirch.

When sharing with strangers, there was the ever-present risk of sexual violence or murder. In the opening chapter of the 1851 novel Moby Dick, the main character is alarmed to discover that the only bed available at an inn would require sleeping with a mysterious – and possibly dangerous – whale harpooner who was in town to sell some shrunken heads.

And there were other, less appealing sides to communal sleep. For all the romance of confidential chats in the dark, and the mutual affection bedfellows developed after years of sharing physical warmth, many shared beds were hotbeds of pests and disease. With so many people crammed onto the same mattress – many of which provided ideal hiding places for insects – they often became infested with fleas, lice or bedbugs.

Alamy

AlamySometimes, sleepers were overcome with the disgusting, overwhelming smells from unwashed bedfellows, ancient bedding and used chamber pots. In one incident Ekirch uncovered, two women accused each other of causing a foul stink, until they realised there was a toilet at the head of their beds.

A gradual decline

By the mid-19th Century, bedsharing began to fall out of fashion – even for married couples.

It all began with an influential American physician. William Whitty Hall, who had strong opinions on many subjects, became a passionate advocate of the idea that communal sleep was not only unwise – but "unnatural and degenerative".

In his book, Sleep, published in 1861, Hall invoked a similar argument to Benjamin Franklin in his tussle over the inn windows: the air in a room occupied by more than one sleeper can quickly become polluted. Moreover, he contented, "it is lowering, because it diminishes that mutual consideration and respect which ought to prevail in social life". Thus, sleeping in the same bed as a companion was not just unhygienic and unhealthy – it was immoral. He even went so far as to suggest it brought people closest to the "vilest" animals in the animal kingdom. Those elderly couples who had survived the great perils of bedsharing for decades of married life had simply been lucky, he suggested.

As the historian Hilary Hinds explains in the book A Cultural History of Twin Beds, this marked the beginning of the rise of individualist sleeping. Families began to abandon the ancient practice of communal sleep – and for nearly a century, many married couples slept apart, in twin beds. This was only reversed in the 1950s, when people began to view separate beds as a sign of a failing marriage. But social sleeping never returned with its previous popularity in other contexts.

So, are we missing out? Should modern politicians swap the photo-opportunity handshake for a symbolic night's sleep, like Richard the Lionheart and Philip II? Or would tourists benefit from sharing a bed with total strangers, as historical travellers did?

"I think people tend to sleep much better when they're sleeping alone for all kinds of reasons… Once you get past the kind of the psychological comfort that sharing beds can bring you, most people benefit from having a sleeping environment that they can fashion for their own bespoke needs," says Handley.

* This article has been updated to clarify that it was the husband of Katherine Parr, Queen Elizabeth I's stepmother, who would burst into the young Queen's bedroom.

--

If you liked this story, sign up for The Essential List newsletter – a handpicked selection of features, videos and can't-miss news delivered to your inbox every Friday.