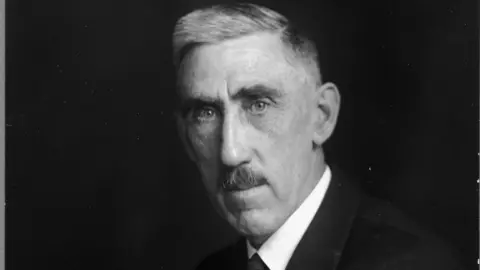

Sir Frank Gill: The engineer who created the 'nucleus' of the BBC

The Institution of Engineering and Technology

The Institution of Engineering and TechnologyIt is almost a century since the BBC broadcast its first radio programme and laid the foundations to it becoming the national broadcaster, but without the tenacity and diplomacy of a largely forgotten engineer, the corporation may have had a very different beginning.

Unlike his pioneering associates Alexander Graham Bell, Guglielmo Marconi and John Logie Baird, Sir Frank Gill is not a household name.

Born on the Isle of Man and raised on the Merseyside coast after the death of his father, he grew into a respected engineer who played a "fundamental" role in the founding of the BBC in 1922, according to the author of a new book about him.

Historian Bob Stimpson says that without the Manxman's influence, the broadcaster may never have been the single entity it has been for almost 100 years - and may even have had a different name.

Manx National Heritage

Manx National HeritageBorn in Castletown on 4 October 1866, Gill was sent to live in Southport with his uncles at the age of 11 and developed such an interest in the recently-invented telephone, that in 1882, he left Merseyside to join London's National Telephone Company.

His talents saw him rise through the firm's ranks - by 1896, he was the company's superintendent of Ireland and in 1902, he returned to the UK as its chief engineer.

He left the firm when World War One broke out and, after being made an OBE for his work at the Ministry of Munitions, he took up the post of European Chief Engineer at the London headquarters of the US firm Western Electric Company in 1919.

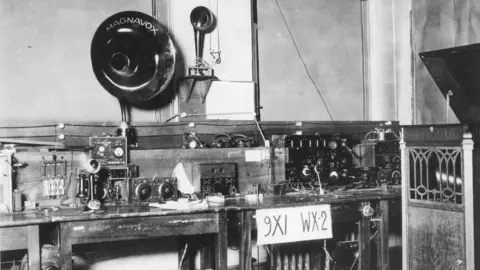

His appointment coincided with an explosion of interest in radio.

Radio was mostly a hobby in the UK at the time, with amateurs building their own sets, but in the US, the medium had boomed, with more than 550 stations broadcasting across the country.

Getty Images

Getty ImagesHead of BBC History Robert Seatter says the prospect of the same thing happening in Britain raised concerns.

"The Post Office, who managed telegraphy and telephony and all of those nascent technologies, looked towards America.

"They said 'we must address this before we get that sort of chaos'."

Bob Stimpson says the idea at the time "was that the manufacturers would make and sell radios... and that would grant them the money to provide the radio programmes".

So, with no national strategy in place, a meeting of interested parties was called to try and get manufacturers to work together, rather than compete in the way US firms were.

He says the records show Gill faced down the two companies, "banged their heads together and insisted they bury their differences and go for the single organisation with a public service approach".

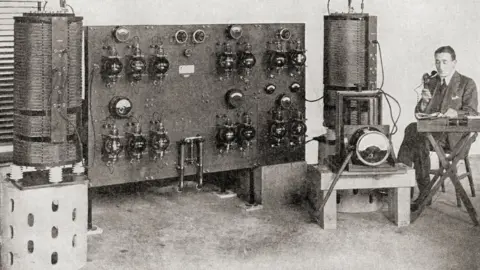

Getty Images

Getty ImagesGill, who was president of the Institution of Electrical Engineers, chaired the first meetings and, in one speech to the assembled companies, stated his firmly-held belief that there should be a "first class broadcasting service unhindered by patents".

Mr Stimpson says it was Gill's skills of diplomacy that made him perfect for the role, as two of the biggest manufacturers, Marconi and Metropolitan Vickers, had different ideas.

"Marconi and Metropolitan Vickers were absolutely insistent that they would go their separate ways," he says.

"Frank had been over to America [where] they had no regulation and no legislation, so companies would start up in a back garden and they would block other transmitters when they switched theirs on.

"It was organised chaos, so the Post Office and Frank could see that they did not want that chaotic arrangement to appear in the UK."

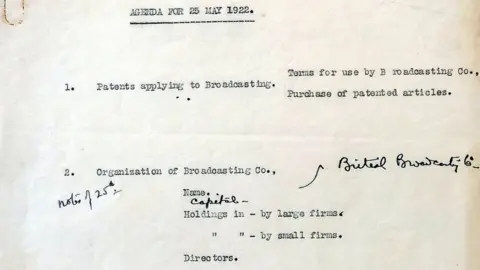

BBC Written Archive

BBC Written ArchiveGill held the role of chairman until July 1922, when he handed over to Sir William Noble, and he never wavered from his belief that a single organisation should manage Britain's radio output.

"He foresaw the issues of multiple organisations competing and it was he who was able to push the discussions towards this single unity," Mr Stimpson says.

"Then Sir William Noble took over and he was able to take that forward and then Lord Reith took on overall direction and it was he who did the final shaping of the nucleus that was created by Frank."

By August 1922, Gill had left for a new job in the US, but not before he had achieved a consensus among the companies, who agreed on the name he had suggested - the British Broadcasting Company - a moniker it kept until 1927 when it was established by Royal Charter as the British Broadcasting Corporation.

The BBC's first transmission followed in November 1922.

Getty Images

Getty ImagesGill, who went on to be knighted in 1941 for services to the telephone industry, continued to work relentlessly until his death in 1950, helping to set up the first transatlantic radio telephone call and telephone networks in Spain and Japan.

But for Liz Bruton, curator of technology and engineering at the Science Museum, it is "his role in the establishment of the BBC" that he should be best remembered for.

"I think what comes through throughout his life is that he's very good at bringing people together and persuading them to look at the importance of telecommunications to companies and individuals," she says.

"Essentially, as a result of Gill's diplomacy and the suggestion of the name British Broadcasting Company, he manages to get all of the companies on board.

"From thereon in, the BBC goes on to be massively successful... and it's essentially the model for public service broadcasting that we have here in the UK and throughout the world."

Why not follow BBC Isle of Man on Facebook and Twitter? You can also send story ideas to [email protected]