Coronavirus: How could social distancing in schools work?

Getty Images

Getty ImagesAs pupils begin returning to classrooms in parts of Europe for the first time since the Covid-19 outbreak shut them, questions are being asked about how re-opening schools could work in Wales.

The Welsh Government has said there will likely be a phased return for pupils but measures to protect all concerned must be in place.

Headteachers are trying to work out how it will work with social-distancing.

But one expert believes opportunities for longer-term change could emerge.

How will schools practice social distancing?

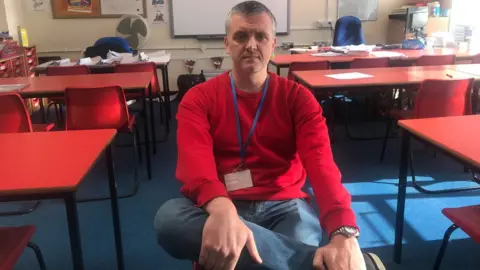

Meurig Jones, the head of Ysgol Gyfun Gymraeg Llangynwyd, a Welsh-medium secondary school in Maesteg, Bridgend county, said he is "desperate" to re-open but only when it is clear to everyone it can be done safely.

First Minister Mark Drakeford has said schools will need three weeks' notice between any announcement and opening their doors, but Mr Jones does not believe that is long enough.

"Three weeks is a long time, but it isn't enough with the practicality of thinking about what needs to be put in place", he said.

His school welcomed 650 pupils each day before the pandemic and he is concerned about arrangements for social-distancing and staffing, as well as the practicalities of pupils travelling to school.

He said: "Ninety-eight per cent of our learners come to school on a bus. So how do we do the social distancing on buses to get those learners in?

"It's also the type of building that we have - this is a building that ranges from the 1950s to the 1980s and has been adapted over the years, yet our corridors are very narrow and our classrooms are relatively small."

He said the normal ratio of one teacher to a class of 30 pupils might have to change to three teachers to just 10 pupils.

"How do we staff that? And how do we ensure that we've got an expertise in all fields?"

The Welsh Government has talked about a "phased" approach to reopening schools, and the first minister has mentioned the possibility of prioritising pupils in the final year of primary school and those in the middle of GCSE and A-level courses as well as Welsh-medium schools.

Mr Jones said he would welcome that, adding that many pupils from English speaking homes may lose confidence in the language and will need help to ensure they are on the "same level playing field" as their counterparts in other schools.

But any move to let pupils go back will depend on the public having confidence in the plans.

"Parents have to feel happy, but also staff have to feel happy - they have their own families as well that they need to take into consideration", Mr Jones added.

How has the re-opening of schools worked elsewhere in Europe?

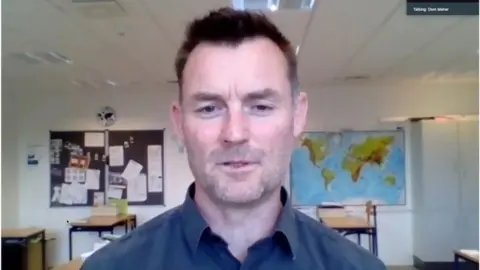

Dom Maher

Dom MaherIn Denmark, schools reopened for the youngest children on 15 April and, according to one teacher, public confidence has grown since then.

Dom Maher, a teacher at St Josef's school in Roskilde, on the Danish island of Zealand, said sharing information with parents and staff about the practicalities of how the school would operate was important.

Asked what lessons there could be for Wales, he said it took time for families "to get their heads round things".

"There were many unknowns and there was a level of anxiety among families," he said.

"By the second week we saw the numbers increase, and that's been happening as I think people have realised that opening schools in a controlled way can work."

Can coronavirus change the way schools work for the better?

There are some who believe the crisis could offer an opportunity to re-think some elements of how schools work alongside addressing the immediate health concerns.

Last year, Prof Mick Waters was asked to chair an expert panel for the Welsh Government on 'reimagining schooling', and to examine school structures, which have been in place for more than a century.

"The sorts of things that people wanted to talk about was things like changing the terms and holiday arrangements, the school days, so that they'd be more family friendly both to the communities that these schools served and also to the teachers and other staff who worked inside them," he said.

He said people also wanted to talk about the ways in which schools could be community hubs where social care and health services might be available.

"And a big push on how we use digital technology properly, both within and outside the school setting. So a lot of things that are very relevant to the current crisis," he added.

"I think what we have learned is that flexibility is possible and people will work to make a different situation happen," he said

Prof Waters believed the crisis had highlighted the value of schools in society and he hoped that other lessons about ways schools could change would be taken on board.

"I think we need to be brave as a society and a schooling system to say, let's take forward what we've learned and gradually change the system for the benefit of children, rather than to rush back to things that have been in place for 150 years and are well out of date."