Forgotten history: The black missionaries of Colwyn Bay

Marian Gwynn

Marian GwynnAs Wales has been observing Black History Month, the near-forgotten story of the African Training Institute in Colwyn Bay, known locally as the Congo House, has received renewed interest.

Black History Month is an annual celebration of identity that started in America in the early 1900s and has since spread across the world. A series of events across the country marked the 10th anniversary of the celebration in Wales, commemorating often overlooked culture and history.

The story of the Congo House is tragic and inspiring in equal measure.

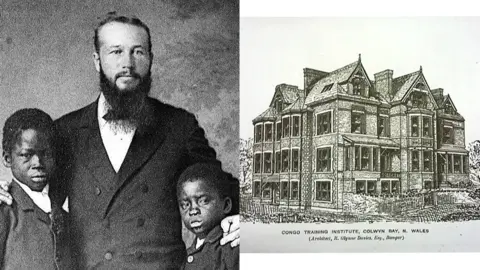

The Reverend William Hughes preached in the Congo from 1882 until poor health forced him to return to Wales in 1885.

He brought with him two students: Kinkasa and Nkansa, the Congo Boys. He and his new companions toured Welsh chapels, giving lectures in different languages, raising funds and selling photos.

In 1887 Mr Hughes, his wife and his African colleagues settled in Colwyn Bay, where he would establish the Training Institute three years later.

The idea of the institute was novel - rather than training white missionaries to preach in Africa, where they would have no immunity to disease or personal connections with locals, the most promising African students would be sent to Britain.

There they would be trained in a variety of useful skills, such as law or medicine, so that when they returned they could support their communities themselves.

By 1903 more than 20 students from nations like Cameroon, Nigeria, Sierra Leone, Liberia and the United States were training at the institute; by the time it closed more than 100 would have passed through its halls.

"Merely a lack of opportunity"

"Unlike other missionaries, he did not want to turn Africa into 'Little England'," explained academic Marian Gwyn.

"He cherished what was different about the people he met in the Congo because he felt that his own Welsh language, culture and traditions had been undervalued by the English back in Britain.

"He wanted black people to have the same advantages as whites, and what many in Europe at that time saw as a lack of ability in Africans, he saw as merely a lack of opportunity.

"He wrote of the black people he met: 'They are like our brethren, of the same blood, the same humour, the same in everything, excepting in education and training'. And he decided to give them those things."

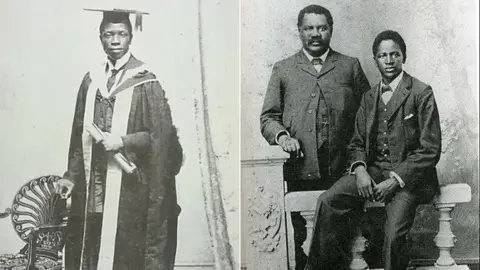

One student, Davidson Don Tengo Jabavu, studied in Colwyn Bay before earning degrees from University College London and Birmingham.

DDT Jabavu would later return to Africa, where he set up the South African Native College at Fort Hare in the Cape Province. It was there he would teach a young Nelson Mandela.

The future South African leader acknowledged Davison Jabavu as one of his most important mentors who helped shape his attitudes on equality.

Marian Gwynn

Marian GwynnAfter a scandal in 1911 involving a Welsh girl bearing the child of one of the students, public opinion turned on the Reverend and his institute, spearheaded by the populist magazine John Bull and editor Horatio Bottomley.

Mr Hughes attempted to sue for libel in 1912, but financial issues led to the case being thrown out and the Reverend declared bankrupt. The institute closed and its students scattered.

Mr Hughes died in a workhouse in 1924, and was buried in Old Colwyn Cemetery alongside members of his family and those students who had died before him - including his first companions Kinkasa and Nkansa.

Kinkasa had died at the age of 13 of "Congo Sleeping Sickness" in 1888, not long after arriving in Colwyn Bay.

Nkansa survived longer, learning Welsh and English, as well as the New Testament in its entirety. Though he wanted to return to Africa, Nkansa would also die young in Wales, succumbing to heart failure in 1892 at the age of 16.

"Their importance cannot be overestimated"

Marian Gwyn said the importance of Mr Hughes and his African Institute "cannot be overestimated".

She added: "He showed how people of different backgrounds and skin colour can learn from each other, share skills and appreciate difference.

"We live in a world that is rapidly changing and attitudes to those who we see as different are hardening.

"His vision on how people can live together - by recognising and respecting difference and by helping to improve the lives of those with fewer advantages - is one that we sorely need in our time now.

"He was truly a remarkable man."