Cumbria coal mine plan 'damaging PM's reputation'

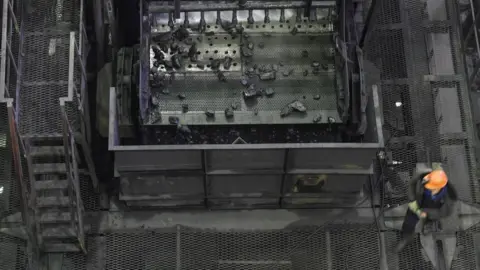

West Cumbria Mining Company

West Cumbria Mining CompanyBoris Johnson has been warned by some of his foreign ambassadors that a planned coal mine in Cumbria is damaging his reputation.

The PM wants to lead the world on climate change, but the ambassadors say his tacit support for the mine is bringing accusations of hypocrisy.

The issue has flared as the UK co-hosts a coalition of nations pledging to phase out coal in power generation.

The Powering Past Coal Alliance (PPCA) was initiated by the UK.

Supporters of the Cumbria mine argue it should be encouraged because it will produce special coking coal for steel making, not thermal coal for power.

But that's too fine a distinction for some developing nations.

They have accused the UK of hypocrisy for shunning one type of coal while backing another.

I understand some of the UK's ambassadors have told the government the Cumbria controversy is making it harder for them to persuade other nations to contribute fully to the UN climate summit Mr Johnson will host in November.

Opponents of the mine say the government must support clean technologies to make steel without using coking coal.

Prickly dilemma

It's a prickly dilemma for the PM. Around 85% of the coal from Cumbria will be exported but the project will create well-paid employment in so-called Red Wall constituencies whose Conservative MPs have promised to increase job prospects.

The mine area has slightly below average unemployment, but it's forecast that manufacturing jobs in the north of England will be especially vulnerable as the UK economy moves away from fossil fuels. The government has a challenge to replace these with new jobs in clean industries.

The UK's stance on coal will fall under the spotlight on Tuesday when the UK and Canada co-host the first virtual summit of the PPCA, which will be addressed by UN Secretary General Antonio Guterres.

The Cabinet Office hopes the Cumbria problem can be resolved by then.

If the mine goes ahead, it fears climate talks will be soured through the year as the UK invites other nations to abandon coal.

In any event, the fate of the mine is in limbo. Cumbria County Council first approved it, then withdrew the decision to consider the latest advice from the UK's independent Climate Change Committee.

This says the UK should abandon the use of coking coal by 2035, unless its emissions are captured and buried underground.

New rules?

Europe's major steel producers are already striving to make low-carbon steel, but Mark Jenkinson, a Conservative MP in the constituency next to the Whitehaven mine, thinks that will not be economical by 2035.

He and other Conservative MPs have criticised the Labour party for trying to block the mine on climate change grounds.

The council will make a new decision on the mine in coming months. If it grants permission again, the issue will bounce back to the Communities Secretary Robert Jenrick to decide on it. First time round he said it was purely a local issue.

One solution might be for the government to introduce new rules obliging local councils to take climate change implications into account when they consider planning applications for high-carbon projects.

Getty Images

Getty ImagesThe UK is not alone in wrestling with policy tensions in the transition to a low-carbon economy, especially as fossil projects approved years ago come to fruition in a new era when permission is likely to have been denied.

Germany is also a member of the PPCA, yet it opened a new coal-fired power plant last year.

Canada has committed to phase out coal-fired electricity by 2030, but there are plans for new and expanded coal mining production in the west of the country.

It all comes as major emitters are again accused by the UN of not doing enough to combat climate change.

A global stock take of plans for emissions reductions showed that nations would only stabilise emissions overall by 2030 - instead of halving them, which is deemed necessary to avoid global temperatures rising above the threshold of 1.5C.

Follow Roger on Twitter @rharrabin