Covid: Vaccine or no vaccine, we have to get through this first

Getty Images

Getty ImagesAfter the euphoria of a vaccine breakthrough, it did not take long for the virus to provide a reality check. Within days of the news that an effective vaccine may have been found, it was being announced the UK was the first European country to pass the grim milestone of 50,000 deaths. This was quickly followed by a record rise in new cases with 33,400 reported on Thursday.

Both are a clear reminder, if we needed one, that there are many more difficult days to come. So what's in store?

The vaccine is no magic wand

Health Secretary Matt Hancock has promised the NHS will be ready to start rolling out the vaccine from 1 December if its passes its final regulatory hurdles.

But that doesn't mean the epidemic will be brought to a sudden halt. There is a huge logistical exercise in vaccinating large numbers of people - the UK has bought enough for 20 million people. And don't forget, unlike the flu vaccine, this one requires two doses.

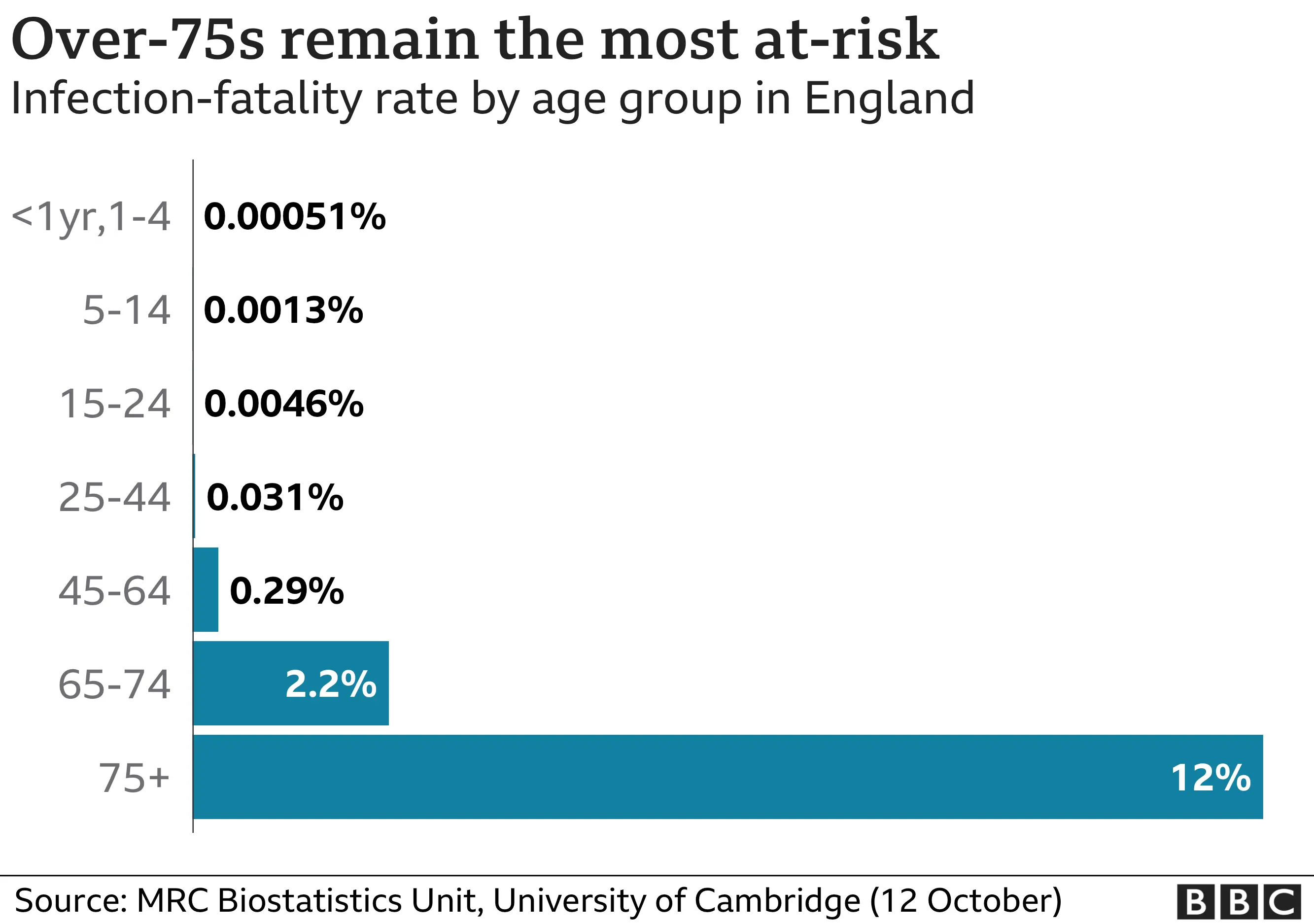

Health and care workers along with older age groups will be prioritised. But given it takes a month from the first dose for an individual to get the full protection and the fact there are 12 million over 65s - nine in 10 deaths have been in this age group - winter is likely to be well gone by the time significant numbers are protected.

England's deputy chief medical officer Prof Jonathan Van-Tam was unequivocal this week when he said he didn't see the vaccine "making any difference" this winter.

Infection rates are high

In the meantime infection rates remain high. Despite seeing over 30,000 cases on Thursday, the UK is averaging over 20,000 confirmed infections a day.

However, estimates from the government's surveillance run by the Office for National Statistics suggests the true figure may be double that.

The situation has left hospitals dangerously close to capacity in the most hard-hit regions. NHS trusts in Birmingham, Liverpool, Leeds, Nottingham and Bradford have all announced the cancellation of non-urgent work to free up beds.

Chris Hopson, of NHS Providers, which represents hospital managers, warns staff are "exhausted" and "traumatised". If hospital cases keep rising it will quickly begin to affect non-Covid work even more, he says.

Lockdown may be followed by... lockdown

We were always warned lockdown, which is under way in England, would take time to have an impact. The good news is that cases had started to stabilise before it came in, with strong evidence the regional tiers had begun to have an impact.

If the rise in cases on Thursday is a blip - there are suggestions it may be linked to a last bout of socialising before lockdown came in - the expectation is the number of infections will soon start to drop. Friday's figures were 6,000 cases down on the day before,

Prof Tim Spector, who runs the Covid Symptom Study, an app which one million people use, believes the crucial R number - the measure of how many people an infected person passes the virus on to on average - is now below one. This would mean the epidemic should start to shrink.

But no-one knows exactly what sort of impact lockdown will have. There have been suggestions the number of infections could be reduced by three-quarters.

But the early evidence from Wales' 17-day fire-break is that it stemmed the rise in cases rather than significantly shrinking it. There could be a delayed impact and England's lockdown is longer, but clearly nothing is guaranteed. Northern Ireland, meanwhile, has just extended some of its national restrictions because of concern about infection levels.

And the problem is that once lockdown is lifted in England, cases are likely to take off again. It is, after all, winter, when respiratory viruses tend to thrive.

Does that mean another lockdown in a few months? This is the nagging fear.

Ministers are just "deferring the problem", says Prof Mark Woolhouse, an expert in infectious diseases at Edinburgh University, who sits on the government's committee on modelling. Even if we had had the lockdown earlier, as some scientists had argued, we would have already been talking about the next one.

More testing, more tracing, but enough isolating?

Those backing lockdown argued it could be used to fix the test-and-trace system, which identifies close contacts of infected individuals and asks them to isolate. Each nation runs its own tracing service, but all have faced the same problem - such high rates of infection make test-and-trace more difficult and less effective.

In England, councils are working hard to set up local teams to support the national system. But most of these are in their infancy and will take some time to bed in. The government has started piloting mass testing in the hope it could be a way of containing the virus given significant numbers of infected people show very mild, or even no, symptoms. The first pilot in Liverpool has been followed by others being set up in more than 60 local authority areas.

Reuters

ReutersBut some question how effective this approach will be.

The rapid tests being used are "not fit for purpose" says Prof John Deeks, an expert in testing at Birmingham University. He points to evidence suggesting they may miss up to half of Covid cases.

He also says identifying previously undetected cases only works if those that test positive isolate. Evidence on those going through the standard testing process is that they are not always doing this. A need to work and earn money is, understandably, a key issue.

The virus isn't going away

This brings us back to vaccination. While the breakthrough is great news, the jury is still out as to how much impact it will have. For example, we don't know how well it works in the elderly, whether it stops people passing it on or simply stops them getting ill or how long immunity lasts.

Even with the vaccine the virus is "not going away", says Sir Jeremy Farrar, a member of the government's Sage advisory group.

It is, he says, now part of humanity and here to stay. Instead, the most we can hope for is providing some protection to those who are most at risk.

The sad reality is that, despite the vaccine breakthrough, we are still going to have to learn to live with Covid this winter - and beyond.

Follow Nick on Twitter