Grammar schools: Some still failing to let in poorer pupils

BBC

BBCA quarter of England's state grammar schools still let in hardly any poorer children, despite most trying to improve their admissions policies, according to BBC analysis.

Out of 160 grammar schools, 116 now have quotas or give high priority to disadvantaged children - but the impact is patchy.

A leading academic says some appear to have made only a "token effort".

The government says it's reviewing how to make grammars more inclusive.

The concern that grammar schools have become the preserve of better-off families has led to pressure for change.

Grammars educate just 5% of secondary pupils in England - but their existence in a local area affects more than just the pupils who go there. For every grammar school pupil, roughly three more go to nearby non-selective schools.

There is evidence that these children do less well at GCSE level than those pupils in areas where there are no grammars, only comprehensives, a House of Commons library briefing paper says.

The latest BBC analysis found that in a quarter of the 160 grammar schools, fewer than 5% of children were eligible for pupil premium support - which is linked to free school meals and used as a measure of disadvantage.

In contrast, only 13 of the more than 3,000 other state secondary schools across all of England have such a low level of pupils from the poorest families.

Seven years ago, the BBC found that most grammar schools did not have policies aimed at making it easier for children from the poorest families to get a place.

Our new investigation has found:

- Three times as many grammars have a quota of places for poorer pupils than in 2016

- A few have also lowered their entrance test pass marks for poorer pupils

- A small minority still give no priority to disadvantaged pupils at all

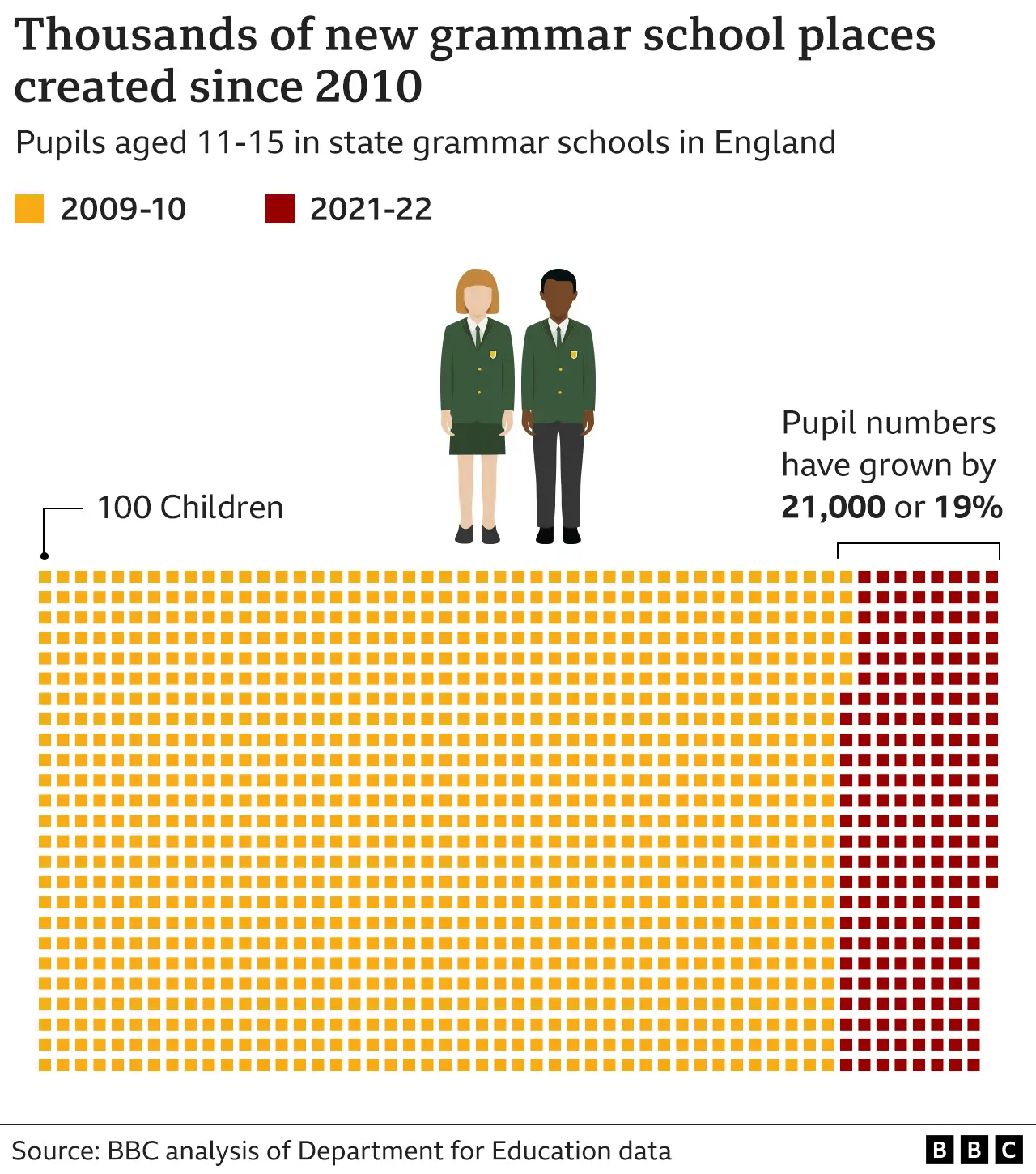

- Grammar school places have increased by 19%, faster than total pupil numbers.

If you live in an area with grammar schools you can find out more by looking them up here:

The King Edward VI grammar schools in Birmingham are among the few to have achieved radical changes, by introducing a quota of 25% of places for pupils from the lowest income families.

In their Camp Hill Girls School, Alishba, 17, has benefited from that policy and is hoping to be a lawyer. She thinks it's important grammar schools are not just "a privilege of the middle and upper classes" because pupils from a wider range of backgrounds have a lot to offer.

"I think I do," she adds.

ZamZam, who is 16 and hoping to study medicine, says going to grammar school has given her more self belief than her siblings, who have attended non-selective schools.

"Nobody has said [to me] 'maybe change your career, you might not be able to make it there', which I've heard is the case in a lot of comprehensive schools."

Grammar schools now more fairly represent the local communities they serve, says Jodh Dhesi, chief executive of the King Edward VI Foundation.

"That's what grammar schools should be about. They should be an academic elite, that's why they're there - but not a social elite," he says.

Has this issue affected you and your family? Get in touch.

- Email [email protected]

- WhatsApp: +44 7756 165803

- Tweet: @BBC_HaveYourSay

- Please read our terms & conditions and privacy policy

But at other grammars, there is often resistance to change. One head teacher told us about his struggle to move his school, funded by state money, away from being like a "pseudo-independent school".

A non-binding agreement between the government and all the grammars, setting out how the schools could be more inclusive of low-income families, expired in December. The Department for Education is now reviewing what should happen next.

Why the schools we looked at are different

Grammars select children using an academic test known as the 11-plus.

While many areas moved to a comprehensive system in the 1960s and 70s, areas that still have grammar schools include Plymouth, Kent, Essex, Wirral, Walsall, Birmingham and Liverpool. Northern Ireland also retained them.

There are some other schools that have kept their historic "grammar" name, but they are either non-selective comprehensive or independent fee-paying schools.

In West Yorkshire, Oliver has passed the test for Heckmondwike Grammar School and is waiting for confirmation that he has a place for this September.

He wanted to go to the school, and so - like many parents in grammar areas - his mum, Laura, paid £30 a week for tutoring to help him pass the test.

Laura, a driving instructor, says the extra hour of study each week for a year definitely helped her son to pass, as did repeated practice tests.

"I think for someone like Oliver, because he does like being pushed, and stretching himself, being surrounded by like-minded pupils will push him along," she says.

Oliver will find out if he has a place on 1 March, when Year 6 pupils across England are told which secondary school they will be attending in September.

How have grammar schools changed?

Grammar schools have expanded since 2010, adding many more places to meet demand. Since 2018, 22 schools have received cash for new buildings from a dedicated fund in return for a promise to become more inclusive.

They include Stretford Grammar School in Greater Manchester, where the number of pupils receiving pupil premium funding fell from 24% to 15% of the school, in the past decade.

In its funding bid, it set a target that may prove near impossible to meet on time. It hopes that by September, a fifth of children in each year group will be eligible for the funding linked to free school meals.

In 2016, when we looked at the admission policies of all 163 grammar schools the majority gave no priority to poorer children in allocating places.

This time, we left out three schools that admit at age 13 and looked just at the 160 grammars where pupils join at age 11 - because they are most comparable with all other secondaries.

Our findings include:

- The biggest shift has been in schools setting aside places in quotas for disadvantaged pupils - from 21 in 2016, to 65 in 2022. Some of them have also lowered the pass mark

- Another 51 schools have put disadvantaged pupils at the front of the queue in their policies when allocating places

- Two more have lowered the required entrance exam pass mark

- But 22 schools make no mention of, and don't give any priority to, poorer pupils in their admission policies for 2022-23

- 17 schools give a lower or limited priority - or put poorer pupils after siblings, distance or even the children of staff

A third of grammar schools now have online practice tests available to make it easier for those who don't have access to private tutoring, the Grammar School Heads Association says.

Why are grammar schools still controversial?

The rights and wrongs of the grammar system have been argued over for decades, but in recent years many had acquired a reputation of being posh - quite different from the more classless ideal people remember from the mid-20th Century.

We asked Prof Lindsey Macmillan, at University College London, to look at our work because she is an expert in education and its impact on life chances.

She said the evidence was "very, very clear" that children in grammar schools areas who don't get a place have reduced opportunities.

"They're less likely to go to university, they're less likely to earn as much as adults.

"Grammar schools increase inequality - compared to comprehensive areas that look very similar in other ways."

But the head teacher who spoke to us anonymously said trying to make his school more socially equal was hard - with his grammar being seen as somewhat of an "ivory tower" by some, and too "posh" by others.

Better-off parents were keen not to lose the advantage they had gained by paying for their children to have tutoring, while poorer parents needed convincing that their children would be welcome at the school, he said.

Grammar schools have been expanding for more than a decade, but could that stop if there was a change in government?

In response to the BBC's analysis, Labour's shadow education secretary Bridget Phillipson welcomed the changes to admission policies - but said it was clear there was a long way to go.

"My focus is driving up the standards in every state school," she said.

She added that "structural reform" of the kind that would see the status of grammar schools threatened was not a policy priority for Labour.

The Department for Education told us they were working to encourage "all schools including grammar schools" to do more to increase access for disadvantaged children.

Additional reporting by Sallie George and Paul Kerley.

Follow Branwen Jeffreys on Twitter

Methodology

Admission policies are taken from each school's website.

The analysis of the change in pupil numbers uses data from the schools census published by the Department for Education. It looks at the change in the number of pupils aged 11-15 (school years 7-11) in 160 grammar schools in England between 2009-10 academic year and the 2021-22 academic year.

It then compares the change in the number of 11-15 year olds in school in the local authority over the same period. In Bournemouth, where the local authority boundaries have changed, the analysis uses the change in the number of pupils in schools in the old Bournemouth local authority area.

Data excludes three grammar schools that have not taken children from 11-15 for the entire period covered. These are:

- Poole Grammar School

- Parkstone Grammar School, Poole

- Cranbrook School, Kent

Pupil Premium data comes from the Pupil Premium Allocations produced by the Department for Education.

Has your family been affected by any of the issues raised here? You can share your experience by emailing [email protected].

Please include a contact number if you are willing to speak to a BBC journalist. You can also get in touch in the following ways:

- WhatsApp: +44 7756 165803

- Tweet: @BBC_HaveYourSay

- Upload your pictures/video here

- Or fill out the form below

- Please read our terms & conditions and privacy policy

If you are reading this page and can't see the form you will need to visit the mobile version of the BBC website to submit your question or comment or you can email us at [email protected]. Please include your name, age and location with any submission.