Why detecting methane is difficult but crucial work

Helen Gebregiorgis

Helen GebregiorgisIn and around Washington DC, volunteers and activists have been walking through streets and homes to see how healthy the air is.

They're armed with industry-grade monitors that detect the presence of several gases. The devices look a bit like walkie-talkies.

But they are equipped with sensors that reveal the extent of methane, turning this invisible gas into concrete numbers on a screen.

Those numbers can be worrying. In a 25-hour period, neighbourhood researchers found 13 outdoor methane leaks at concentrations exceeding the lower explosive limit. They have also found methane leaks within homes.

A key concern has been health. Methane and other gases, notably nitrogen oxide from gas stoves, are linked to higher risks of asthma.

Djamila Bah, a healthcare worker as well as a tenant leader for the community organisation Action in Montgomery, reports that one out of three children have asthma in the homes tested by the organisation.

"It's very heartbreaking and alarming when you're doing the testing and then you find out that some people are living in that condition that they can't change for now," Ms Bah says.

Methane might be a hazard to human health, but it is also powerful greenhouse gas.

While it has a much shorter lifespan in the atmosphere than carbon dioxide (CO2), methane is much better at trapping heat and it accounts for about one-quarter of the rise in global temperature since industrialisation.

Methane emissions come from a diverse array of sectors. Chief among these are fossil fuels, waste and agriculture.

But methane is not always easy to notice.

It can be detected using handheld gas sensors like the ones used by the community researchers. It can also be visualised using infrared cameras, as methane absorbs infrared light.

Monitoring can be ground-based, including vehicle-mounted devices, or aerial, including drone-based measurement. Combining technologies is especially helpful.

"There is no perfect solution," says Andreea Calcan, a programme management officer at the International Methane Emissions Observatory, a UN initiative.

There are trade-offs between the cost of technologies and the scale of analysis, which could extend to thousands of facilities.

Thankfully, she has seen an expansion of affordable methane sensors in the past decade. So there is no reason to wait on monitoring methane, at any scale. And the world needs to tackle both the small leakages and the high-emitting events, she says.

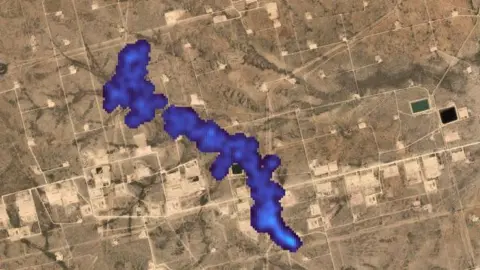

Carbon Mapper

Carbon MapperAt a larger scale, satellites are often good at pinpointing super-emitters: less frequent but massively emitting events, such as huge oil and gas leaks. Or they can detect the smaller and more spread-out emitters that are much more common, such as cattle farms.

Current satellites are typically designed to monitor one scale of emitter, says Riley Duren, the CEO of the Carbon Mapper, a not-for-profit organisation that tracks emissions.

He likens this to film cameras. A telephoto lens offers higher resolution, while a wide-angle lens allows a larger field of view.

With a new satellite, Carbon Mapper is focusing on high resolution, high sensitivity and rapid detection, to more precisely detect emissions from super-emitters. In August 2024 Carbon Mapper launched the Tanager-1 satellite, together with NASA's Jet Propulsion Laboratory and the Earth imaging company Planet Labs.

Carbon Mapper

Carbon MapperSatellites have struggled to spot methane emissions in certain environments, such as poorly maintained oil wells in snowy areas with lots of vegetation. Low light, high latitudes, mountains and offshore areas also present challenges.

Mr Duren says that the high-resolution Tanager-1 can respond to some of these challenges, for instance by essentially sneaking peeks through gaps in cloud cover or forest cover.

"In an oil and gas field, high resolution could be the difference between isolating the methane emissions from an oil well head from an adjacent pipeline," he says. This could help determine exactly who is responsible.

Carbon Mapper began releasing emissions data, drawing on Tanager-1 observations, in November.

It will take several years to build out the full constellation of satellites, which will depend on funding.

Tanager-1 isn't the only new satellite with a focus on delivering methane data. MethaneSAT, a project of the Environmental Defense Fund and private and public partners, also launched in 2024.

With the increasing sophistication of all these satellite technologies, "What was previously unseeable is now visible," Mr Duren says. "As a society we're still learning about our true methane footprint."

It's clear that better information is needed about methane emissions. Some energy companies have sought to evade methane detection by using "enclosed combustors" to obscure gas flaring.

Translating knowledge into action isn't always straightforward. Methane levels continue to rise, even as the information available does as well.

For instance, the Methane Alert and Response System (MARS) uses satellite data to detect methane emissions notify companies and governments. The MARS team gathered a large quantity of methane plume images, verified by humans, to train a machine learning model to recognise such plumes.

In all the locations that MARS constantly monitors, based on their history of emissions, the model checks for a methane plume every day. Analysts then scrutinise any alerts.

Because there are so many locations to be monitored, "this saves us a lot of time," says Itziar Irakulis Loitxate, the remote sensing lead for the International Methane Emissions Observatory, which is responsible for MARS.

In the two years since its launch, MARS has sent out over 1,200 alerts for major methane leaks. Only 1% of those have led to responses.

However, Ms Irakulis remains optimistic. Some of those alerts led to direct action such as repairs, including cases where emissions ceased even though the oil and gas operator didn't officially provide feedback.

And communications are improving all the time, Ms Irakulis says. "I have hope that this 1%, we will see it grow a lot in the next year."

At the community level, it's been powerful for residents, such as those in the Washington DC area, to take the air pollution readings themselves and use these to counter misinformation. "Now that we know better, we can do better," says Joelle Novey of Interfaith Power and Light.