Versatile poet's work ranged from nature to civil strife

Getty Images

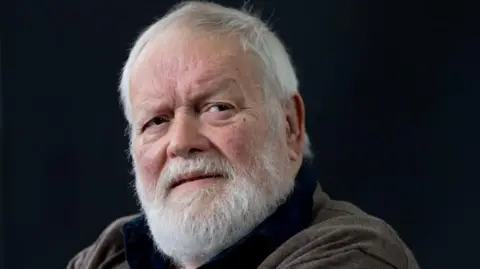

Getty ImagesRead and celebrated across the globe, Michael Longley was born in Belfast in July 1939 and lived in the city until his death.

He went to school at Royal Belfast Academical Institution, where a lifelong enjoyment of rugby began.

In the late 1950s he moved to Dublin to study at Trinity College Dublin and it was there, in the company of fellow student poets, including Derek Mahon and Brendan Kennelly, that he became immersed in poetry.

His death was announced on Thursday at the age of 85.

Getty Images

Getty ImagesAt Trinity he met his future wife Edna - later a professor at Queen's University Belfast (QUB) and a notable critic and writer in her own right.

After their marriage in the mid-1960s they settled back in Belfast, where Longley joined a stellar collection of young poets who met regularly to read and talk about each other's work.

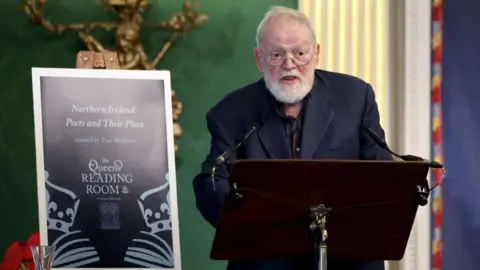

The Belfast Group - as it became known - included Longley, Seamus Heaney, Derek Mahon, Paul Muldoon and others.

They met in pubs close to Queen's University and at the flat of a university lecturer, Prof Philip Hobsbaum.

"It was no way a back-scratching coterie," Longley later recalled.

"The routine would be you'd go for a pint, and you'd have a poem in your pocket.

"And after a pint or two you'd venture to show it to, say, Seamus or Derek."

Getty Images

Getty ImagesAfter Heaney's death in 2013, Longley wrote an elegy called Room to Rhyme about his friend, which was published in his later collection, Angel Hill.

Longley's first collection, No Continuing City, had been published in 1969 - just as the Troubles started in Northern Ireland.

No Continuing City included the poem In Memoriam written in memory of Longley's soldier father Richard, who had been wounded in World War One and later died of cancer.

Longley remained in Belfast as the Troubles worsened, writing a number of collections of poetry while working full time for the Arts Council of Northern Ireland.

Trips with his family to the west of Ireland prompted poetry about nature, but Longley did not avoid writing about the conflict around him.

Poems like The Ice Cream Man, Wounds, Kindertotenlieder, The Linen Workers and Dusty Bluebells reflected the suffering of victims of violence with compassion.

Though Longley was well aware, as he said in a later interview, of the "deadly danger of regarding the agony of others as raw material for your art, or your art as solace for them in their suffering".

In a later article for the New Statesman magazine, Longley wrote: "We disliked the notion that civic unrest might be good for poetry, and poetry a solace for the brokenhearted.

"We were none of us in the front line."

Getty Images

Getty ImagesLongley and Heaney had attended some of the civil rights marches in the late 1960s.

Later, in a BBC Northern Ireland documentary he said he was "overwhelmed and flabbergasted by the ferocity" of the Troubles.

"I still find it really difficult to understand how you can shoot a neighbour simply because of his or her religion," he said.

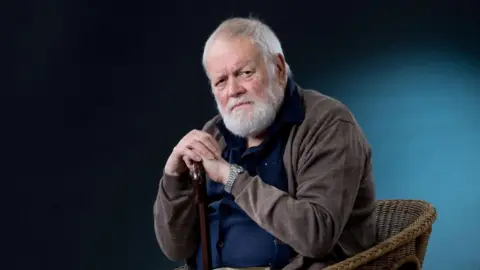

Longley received a number of prestigious awards for his work, including the T.S. Eliot Prize and the Whitbread Poetry Prize.

In 2001, he was awarded the Queen's Gold Medal for Poetry, and late in his career he won the Feltrinelli International Prize for Poetry awarded by Italy's Accademia Nazionale dei Lincei.

Longley also held the post of professor of poetry for Ireland from 2007 to 2010 and was appointed Commander of the Order of the British Empire in the 2010 Birthday Honours.