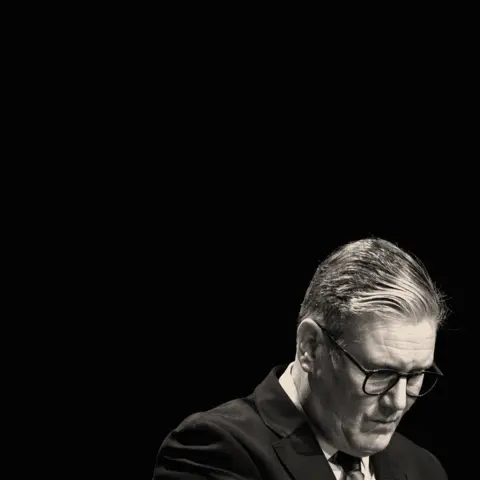

Kuenssberg: Starmer's first year ends in shambles, but could he still turn it around?

BBC

BBC"Who the hell thought this was a good idea?" a Labour insider spluttered, incredulous, even two weeks ago, that No 10 would schedule a vote to take benefits from the disabled as the anniversary of their election victory approached. "What genius!" they mocked.

They predicted drama, although not a disaster like this.

The gory consequences of the decision to try and change the law on welfare this week are there for all to see.

No 10 might have been hanging out the bunting, preparing to celebrate a year in office. Instead, for a few days Parliament has looked just as much of a shambles as during the head-spinning days of incessant Tory turmoil.

Getty Images

Getty ImagesIn this fevered week, Labour has been failing its basic mission, to look like a capable government. And the prime minister's authority has been given a hefty kick.

Westminster has rushed to its default of recent years - salivating over spats and splits, chaos and confusion. But whether that enrages or entertains you, the bald facts here matter to everyone: a government that can't pass laws in Parliament can't effectively wield power. Prime ministers that can't effectively wield power can't get things done.

So can Labour move on from this almighty mess?

A year of 'unintended consequences'

The welfare vote fiasco is far from the first thing that has gone wrong. "They can fix it," one Whitehall source says, but "they have to realise they have caused it and smarten up how they make decisions".

But Labour has had a whole "year of unintended consequences", as one MP described it. That's a diplomatic way of saying it has made plenty of mistakes and a lot has gone wrong during its first year back in No 10.

If nothing else, this government has lost the chance to make a good first impression. And some of the events have been baffling at best, and worrying at worst - inconvenient small embarrassments like Starmer tripping over while leaving No 10, the Chancellor having tears running down her face in the Commons (it's still a mystery why), don't help give a sense that it's all in hand.

As for the welfare row, one member of the government tells me that this nodded to a far broader issue within the party: it has been a "coming together of so many things that have been simmering". It is, they add, self inflicted.

A senior government source says the situation "is disappointing but not overly concerning". You might wonder if they ought to sound a bit more worried.

PA Media

PA MediaWhat has been illustrated this week is that the leadership has not understood what its rank and file are willing to tolerate. And management of the party has been found sorely lacking, spectacularly so.

Ironically one of the reasons some MPs have been so cross, even before this week, is because "the mismanagement creates a fog and a funk", where potentially punter-friendly measures, like providing more free school meals and increasing the minimum wage, are drowned out.

No 10 versus the backbenches

What there is, in the wake of this week's humiliation, is an acknowledgement that things will have to be different. A senior source in government says "we can't leave as much of a gap between ministers and backbenchers", admitting "we'll have to be better at bringing them in".

The prime minister "now realises he'll have to be more into the detail", one minister says. Many insiders believe that there still needs to be a much better functioning "centre", in other words Starmer's own power base in No 10.

It is no longer the "spectacularly ineffective, 70s farce" of the early weeks in No 10 that one senior figure describes, when it took days to work out exactly who was to do what; when Sue Gray and Morgan McSweeney were vying for authority; and when there was near mutiny over pay. But the source says "the legacy of these things takes time to catch up".

Reuters

ReutersInside No 10, there has been acknowledgement it needs to run better, to improve the way decisions are made across Whitehall, well before this week's humiliation.

The way power is spread across SW1 and No 10 makes it "an incredibly weak centre of government, and that was a real surprise for us", say those insiders. "If we accept that No 10 will never be a White House then you need to empower other people to make better government decisions", they say.

But others say there is a fundamental need in No 10 for the prime minister and his top team to be more concerned with "the absolute basics" of politics, warning sometimes there is a tone of being "sanctimonious" not wanting to "do the actual business of politics, even if its grubby". In other words, they can complain about the structures of Whitehall, or the difficulties of what they inherited, but, some argue, they struggle to look in the mirror.

"Everyone needs to do better" including the political team, one MP argues. That might include doing fewer things, but much more effectively. One minister argues "there'll have to be far fewer priorities – small boats, the NHS, welfare and the cost of living … everything else will have to wait".

Reasons to be optimistic

Starmer has been reminded, painfully this week, that the normal activity of politics – charming, cajoling, even sometimes menacing your party, still has to be done even if a party has hordes of MPs.

A majority of this scale is an insurance policy, not free rein. Governments of any flavour are in trouble if the relationship between those at the top and those at the bottom break down. If links inside the party are frayed it becomes harder to present a compelling front to the public.

No 10 must develop "more emotional intelligence", and fast, one MP argues. They believe that Starmer's "human instincts need to get much sharper in year two because of what has happened in year one".

Labour's vast, not so new ranks, are not willing to be bossed around.

But many MPs, advisors, ministers and party insiders I've spoken to can find reasons to be optimistic, even as the embarrassment of the last seven days stings. Spin forward to the summer of 2026 and they predict that the party will be in a much better place. "People will start to notice," as one MP puts it.

Another adviser says "there is hope" – progress in the NHS will "take on more potency".

Getty Images

Getty Images"We have set in train a whole bunch of things, the planning changes, big visible projects, and money for the NHS," says another MP - and voters will see, "maybe there is more going on than we thought".

Another source enthuses that Labour is stacking up progress towards its target of building 1.5 million homes by 2029; that there will be new laws on the statute books rather than in the debating chamber, that protect renters; and that new rights will be given to workers.

Certainly, this spring and summer has seen a flurry of announcements that set a quicker tempo. Downing Street is now "making better, more political decisions – on industry, on investment", according to one senior figure.

Another senior MP hopes "we have now passed a tipping point where there is suddenly a lot happening".

But the question now is, will anybody notice?

Starmer has never been a showman

It's accepted that ministers failed to make their arguments properly to their own party when it came to the welfare mess this week. One minister told me that if they had made a better case, earlier on, they would have been able to get the plans through and avoid all the embarrassment.

Telling the government's story better to the public is absolutely vital if Starmer is to make any progress towards restoring even a fraction of Labour's popularity from this time last year. This is not a revelation to Starmer's inner circle.

They have always been aware that he is not a showman or a politician who can always smoothly adapt to the public situation he finds himself in, choose the right words, or convey empathy or warmth.

Getty Images

Getty ImagesThere is a determination to tell the story better, to define the incredibly broad "change" message that won the election, to move to more specifics, perhaps even spelling out a new "social contract" – a rhetorical tool used by both Tony Blair and Gordon Brown, during their time in power. To do this, MPs tell me that Starmer needs to not only work out exactly how to explain his project but to care deeply about getting it across.

"Where's the hope?" says one MP. "He needs to want it from his team, to tell the story. If he doesn't see the value in it, and they don't hire for it, then they're not going to get it."

The world wreaking havoc

There is a scenario where Labour uses its 12 months of turmoil and learns from it. Starmer's allies say he has so often been underestimated. When the party lost the 2021 Hartlepool by-election, he considered quitting, but instead, he fought back.

Now they could cross their fingers and hope that signs of progress on the NHS turn into a convincing trend. That the big building blocks the government has put in place in the hope of giving the economy a kick start to come good. And that the situation in the Middle East doesn't spiral into anything even more dangerous, and potentially costly to the economy.

But would you bet on it?

Looking at the mess over the welfare plans you might not be confident, yet it would be ludicrous to conclude that the first year in office has been so bad, and the circumstances so tough, that they're a busted flush.

But many MPs and Labour figures worry about what is going on in the rest of the world. "World War Three?" one of them says - they're not quite joking. The US going into recession, further spikes in the oil price, cyber attacks on this country from adversaries like Iran and Russia - there are all sorts of pressures outside the government's control that could wreak havoc with the economy.

Getty Images

Getty ImagesDon't forget there will be a budget in the Autumn, with a broad expectation that more tax rises could be on the way – partly because of the costs of international turmoil, partly because of long term stubborn problems in the UK, and partly because of the consequences of the government's own choices.

The backdrop to year one in government has been incredibly difficult because of these myriad factors. In the next year, the overall context may not get much easier, if at all.

What happens in the rest of the world could "obliterate" the budget choices the chancellor has already made. If the economy turns for the worse because of factors around the world, all bets are off.

One MP expressed some sympathy for No 10. As they put it, "What is the bandwidth when you have Israel, Iran, welfare, and the economy to deal with? There is no lightness in politics."

The risk now is that the growing pains of year one could become embedded political problems in year two. After the welfare struggle, the winter fuel backtrack, and with genuine unhappiness on the backbenches, it is possible that Parliament becomes a regular obstacle for the government.

"Worst case?" says an influential figure on the left, "you'll have a big collective number [in the Commons] saying, well, you are not going to do it", leaving Downing Street as an administration with a big majority but only a small chance of getting things done.

"We might just continue to wobble," adds a senior source, "we have such a huge majority we should be able to be confident and stride out together – but the worst case is, we are still drowning" this time next year.

AFP via Getty Images

AFP via Getty ImagesLocal elections will be held in May next year, and the results will be incredibly important.

The best case scenario at the ballot box? A member of the government says, "Next year is essentially like mid-terms – we could win in Scotland, we do well in Wales and show at least some progress in England."

But the worst case scenario, with Reform gnawing at Labour's vote from the right, and the Liberal Democrats and Greens from the left is "disastrous results in the locals", says one No 10 source.

They predict that Labour is unlikely to hold on in Wales, that it will fail to get far in Scotland - and before long, you're in a "cycle of insecurity", one senior MP warns.

Blood in the water

There are fears too that relationships in the party's top echelons might splinter, some with their own ambitions, wondering if they could prosper as a result of Starmer's difficulties. A senior figure in the Labour movement warns, "you have some people smelling blood in the water – there is some bad behaviour in that Cabinet and people ready to manoeuvre".

One senior figure reckons questions might be asked about Starmer's leadership. "It is bananas", they say, but it is not entirely impossible to imagine that within a couple of years of July 2024's history making win, there could be moves against him.

Another senior source even says, "I don't think there is a cat in hell's chance he leads us into the election".

That talk isn't taken seriously in No 10. "There is no evidence at all of any serious attempt taking shape," one source says. Another MP tells me, "It's ridiculous, it would undermine the thing we are most concerned about which is stopping the chaos of the Tory years."

Yet another, who argues that it would be foolhardy to question whether Starmer will be the leader to take Labour into the next general election, nonetheless acknowledges the conversation is out there.

"It is mindblowing, but people do go there that quickly – they do talk about it."

Could Starmer's bloodymindedness pay off?

It was Starmer and his team's mission not just to win, but to show a sceptical public that government could actually be a force for good in their lives, not a flawed institution attached to hordes of bickering politicians more interested in the sound of their own voices than getting anything done.

To make that happen they need their plans to work – whether it's building houses, or bringing down NHS waiting lists, reducing the number of small boats crossing the Channel, or filling potholes, or incredibly fraught areas such as overhauling welfare or special needs education, or social care.

There's an almost universal acceptance too, throughout Labour, that the government must get better at telling its story. They need to do this to recover in the polls, and avoid a situation where even after two years of a government with an enormous majority, and tens of billions of public cash being spent, the public is still angry, still unconvinced that politicians are ineffective at best - and harmful at worst.

A party veteran warns, "They allowed the heart of the Labour government [to] be almost unfathomable – they must recover the heart, until that is in place, no one will get what we are about."

Getty Images

Getty ImagesBut bluntly, as its been obvious in the last week, and over the last year, multiple sources say this still young government needs to improve if it is to avoid squandering the huge opportunity it still has – not just No 10, not just the civil service, not just party managers, not just the Cabinet but, "it's everyone's job", a minister says.

In the last 12 months, it's been perhaps surprising, as one Whitehall source suggests, that Labour "seems to have been bewildered by the normal business of politics". There is hope among many Labour insiders I spoke to that Starmer's ability to keep going, relentlessly, however bad the circumstances, will ultimately pay off, through sheer bloodymindedness, they will be rewarded in the end – not with love, but a grudging respect from the electorate by 2029.

But the question for the next 12 months - maybe even the next 12 hours or 12 days - is whether the prime minister and his party, can put this year's painfully gained wisdom to good use.

BBC InDepth is the home on the website and app for the best analysis, with fresh perspectives that challenge assumptions and deep reporting on the biggest issues of the day. And we showcase thought-provoking content from across BBC Sounds and iPlayer too. You can send us your feedback on the InDepth section by clicking on the button below.