'He was just an innocent wee boy on his holidays'

FAMILY PHOTO

FAMILY PHOTOWarning: This story contains distressing details

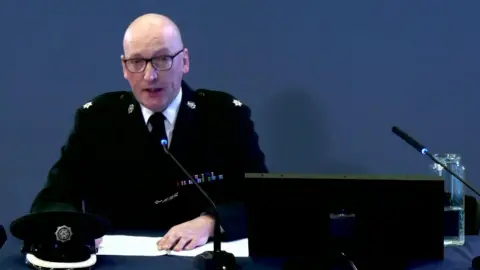

A police officer who was at the scene when the Omagh bomb exploded in 1998 has said the death of a 12-year-old Spanish boy had "the most profound and lasting effect" on him.

Norman Haslett, who is now a superintendent with the Police Service of Northern Ireland, (PSNI) was just two years into his career when the explosion happened.

The Real IRA bomb killed 29 people in the County Tyrone town in August 1998, including a woman who was pregnant with twins.

Supt Haslett had gone into the town following the bomb warning to help oversee the evacuation.

He told the Omagh Bombing Inquiry that what he "saw and heard and smelled" at the moment of the explosion resembled "hell".

"It was pure carnage and chaos," he said.

Omagh Bombing Inquiry

Omagh Bombing Inquiry'Beautiful wee boy'

Supt Haslett said he had been particularly struck by the body of a boy with brown hair, brown eyes and a "Mediterranean complexion".

The boy, he said, was Fernando Blasco Baselga, who was in Omagh as part of a language exchange group.

"The only possession that this beautiful wee boy had on him was a small red Swiss army knife which I found in one of his pockets," he said.

"I was relieved to hear he hadn't suffered any pain. He just looked to me as if he was asleep."

Supt Haslett said Fernando was "just an innocent wee boy on his holidays with his pen knife in his pocket".

"He was murdered for a political cause by people of insignificance whose humanity was indifferent to the consequences of their actions."

'Inhumanity'

Supt Haslett said some victims were "crying out in pain and some were very quiet and still".

"I remember seeing people who were obviously beyond help, some horribly mutilated with arms and legs missing."

The dead accumulated in an entryway, he said, and officers numbered them using "torn up strips of paper and a biro pen".

He said: "Looking back this sounds awful and terribly impersonal but it was the only way we could keep an accurate count of the number who had died and who we had recovered."

Supt Haslett told the inquiry the blankets used to cover the bodies were seeped through with blood stains.

'Horrors'

PA Media

PA MediaAnother police officer who provided first aid to the injured described the "horrors" he had witnessed after the attack.

In a statement read to the inquiry, Allan Palmer, who was badly injured himself, said he was "moving through the terrible scene trying to assist where [he] could".

He saw a young man on the ground with serious facial injuries but "there was nothing [he] could do to save his life".

Mr Palmer also described seeing "a woman lying on the ground with the engine of a car on top of her" and a male "lying near a gutter with his head on fire".

He added: "The memories and emotions that I carry with me every day are too many to include in this statement.

"The horrors, the guilt, the helplessness, the anger, the hurt, and many more have all had a serious impact on both my physical and psychological health."

'There are bodies everywhere'

Richard Scott, a police officer who helped gather the bodies of those killed, told the inquiry he had binned his blood-soaked clothing after his shift to try to "disassociate from the scene".

Mr Scott, who was diagnosed with post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD) after the bomb, described the devastation when he arrived in the town centre with a colleague.

"He said to me, 'This is terrible, there are bodies everywhere'," Mr Scott said.

"I said, 'I'm sorry but I can't see any bodies', and he said, 'Look down at your feet'.

"And I looked down at my feet and there was a body at my feet. And then as I glanced around there I could see bodies to my left, I could see bodies to my right."

Omagh Bombing Inquiry

Omagh Bombing InquiryMr Scott was tasked with moving bodies and body parts from the scene to a nearby entry (alley).

He told the inquiry he had grabbed blankets and curtains for the dead to "give them back their dignity".

"It's one of the most important points that I've tried to emphasise over the years, how we treated the bodies, and how we treated everyone with respect and moved them to the entry and gently laid them down," he said.

Mr Scott said the entry was a reminder to him of the "carnage" that day.

He set up the voluntary organisation Military and Police Support of West Tyrone to help other officers with trauma.

'Stampede' of relatives

Julian Elliot was a police sergeant tasked with setting up an incident centre at Omagh Leisure Centre to help families search for loved ones.

In a statement read to the inquiry, he said there had been a "stampede" of people desperate for news of relatives.

He said that while he could not officially confirm the deaths, he chose to inform people in an unofficial capacity.

"I decided to take my uniform head off and put my human head on," he said.

"I thought if I was one of these poor people, I would want to know.

"Some hugged me, some beat my chest. Some hyperventilated and collapsed on the floor."

Omagh Bombing Inquiry

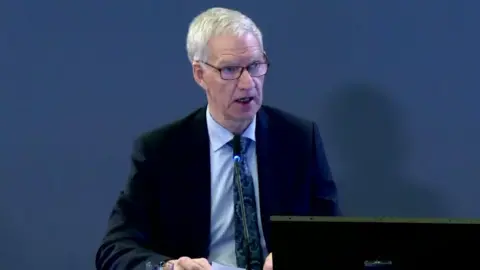

Omagh Bombing InquiryA senior RUC officer who led the police response said many officers "felt guilty and responsible" for moving members of the public to the area where the bomb went off.

The bomb warning said the explosive was at the courthouse in Omagh, but it exploded in Market Street, where civilians had been evacuated.

James Baxter, who was sub-divisional commander in Omagh at the time, told the inquiry he referred some officers for professional counselling.

'Very distressing'

Mr Baxter said he had to maintain a professional manner, while also grieving a personal loss as his son's girlfriend was killed that day.

Visiting the families of the bereaved was "the most difficult and emotional duty" of his career, he said.

Mr Baxter told the inquiry the sight of the bodies laid out in this temporary mortuary was "very distressing" and "brought home vividly the impact of the atrocity that had been inflicted on the people of Omagh".

He said the bomb and subsequent events had such an effect on his well being that he cut his police career short and left the service in 2003.

What was the Omagh bomb?

Press Association/MOD

Press Association/MODThe bomb that devastated Omagh town centre in August 1998 was the biggest single atrocity in the history of the Troubles in Northern Ireland.

Twenty-nine people were killed, including nine children, a woman pregnant with twins, and three generations of one family.

It came less than three months after the people of Northern Ireland had voted yes to the Good Friday Agreement.

Who carried out the Omagh bombing?

Three days after the attack, the Real IRA released a statement claiming responsibility for the explosion.

It apologised to "civilian" victims and said its targets had been commercial.

Almost 27 years on, no-one has been convicted of carrying out the murders by a criminal court.

In 2009, a judge ruled that four men - Michael McKevitt, Liam Campbell, Colm Murphy and Seamus Daly - were all liable for the Omagh bomb.

The four men were ordered to pay a total of £1.6m in damages to the relatives, but appeals against the ruling delayed the compensation process.

A fifth man, Seamus McKenna, was acquitted in the civil action and died in a roofing accident in 2013.