Facial scanning cuts crime at a low cost, Met says

BBC

BBCLive facial recognition technology (LFR) is helping the Met stay ahead of criminals at a time "where money is tight," according to the force's director of intelligence.

Lindsey Chiswick, the lead for LFR at the Met and nationally, said more than 1,000 arrests had been made since January 2024 using the tool, including alleged paedophiles, rapists and violent robbers.

She said it "would be madness" if officers did not keep pace with available technology in order to protect the public.

Privacy campaigners say there's been an "alarming escalation" in police use of LFR, which maps a person's unique facial features, and matches them against faces on watch lists.

Since the start of 2024, a total of 1,035 arrests have been made using live facial recognition, including 93 registered sex offenders.

Of those, 773 have been charged or cautioned.

The tool is also being used to check up on people who have court conditions imposed, including sex offenders and stalkers.

The include 73-year-old David Cheneler, a registered sex offender, who was picked up on LFR cameras in January in Denmark Hill, south-east London, with a six-year-old girl.

"Her mother had no idea about his offending history," says Ms Chiswick. "Without LFR that day, officers probably wouldn't have seen him with that child, or thought anything was amiss."

Cheneler was jailed for two years for breaching his Sexual Harm Prevention Order, which banned him from being alone with young children, and for possessing an offensive weapon.

But some have expressed concerns over the Met's increasing use of LFR, and plans for a pilot scheme in Croydon, south London, where fixed cameras will be mounted on street furniture from September, instead of used by a team in a mobile van.

The Met says the cameras will only be switched on when officers are using LFR in the area.

Green Party London Assembly member Zoe Garbett previously described the pilot as "subjecting us to surveillance without our knowledge".

Interim director of Big Brother Watch, Rebecca Vincent, said it represented "an alarming escalation" and that the technology is "more akin to authoritarian countries such as China".

Ms Chiswick said while she understood concerns, she believed the Met was taking "really small, careful steps".

She added: "I think criminals are exploiting that technology and I think it would be madness if we didn't keep pace with that and allow criminals to have access to tools which police didn't.

"The world is moving fast, we need to keep up."

We joined police on a recent LFR deployment in Walthamstow, where a mobile van was parked up in an area between the Tube station and the market on the high street, a hot spot for theft and robbery.

Officers told me the bespoke watch list, created for each deployment, had been compiled around 5 o'clock that morning, and contained 16,000 names of wanted offenders, and would be deleted at the end of the day.

But before I even reached the van, or spotted the sign alerting that live facial recognition cameras were being used, officers had already spotted me.

My face had been scanned, and flagged as a potential match to my photo, which police had earlier added to their system so we could demonstrate how it worked.

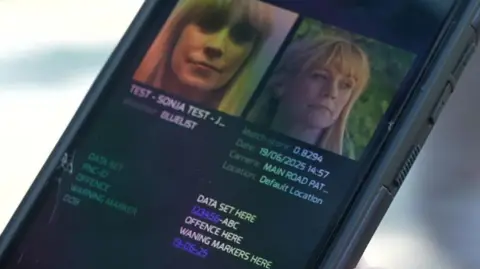

The officers' handsets bleeped, as the two images blinked up on their screens.

In this case, it was a 0.7 match. Anything less than 0.64, they said, is considered unreliable and the captured image is deleted.

"I've got no wish to put technology on the streets of London that is inaccurate or biased," Ms Chiswick told me.

She said that the threshold had been selected after tests by the National Physical Laboratory .

"All algorithms have some level of bias in them. The key thing for police to understand is how to operate it in order to ensure there is no bias at that level."

The two images of my face were also flagged to the team inside the mobile van.

They showed me their monitors, where the cameras were scanning all the faces in the crowd, before quickly pixilating them.

If it is not a match, officers told me, their biometric data is immediately deleted.

If someone on the list is identified by the system, police officers then take over.

"Live facial recognition is meant to work alongside your natural policing skills," explains Supt Sarah Jackson, "so you should be able to approach those people that have been activated by the cameras, go and talk to them and ascertain if the cameras are correct".

But what happens when the cameras get it wrong? How do those people react?

"That does happen on very few occasions" Supt Jackson acknowledged.

"There's always the possibility to upset people in any walks of life if they're stopped by police. But by and large, people are happy."

Ms Chiswick said since January this year, there had been 457 arrests and seven false alerts.

During the Walthamstow deployment, police told me eight arrests were made including for drug offences, stalking and driving offences, and that there were no false alerts.

It's not just campaigners who are concerned over potential misidentification.

Local resident Christina Adejumo approached me to ask why she'd just seen a man being handcuffed in the middle of the market.

When I explained he'd been picked up by the live facial recognition cameras she told me she thought they were a good idea, but questioned their accuracy.

"It can be said, 'sorry, it's not you', but the embarrassment of what happened that day cannot be taken away from him."

Ann Marie Campbell said: "I think it's a good idea because of public safety." She also hoped it would help tackle pickpocketing.

"This is very good to prevent crimes," Ansar Qureshi agreed.

Is he worried about privacy? "I don't mind, because I don't have anything to hide," he told me.

But Caroline Lynch said she was "disgusted" by the technology. "I don't feel safer, no. It's just more and more 'Big Brother'."

She insisted she'd rather the money was spent on safety measures including putting more police on the streets.

"I can get on to the Tube at 12 o'clock at night and there's absolutely no-one there to protect us."

Earlier this year, the Met Commissioner Sir Mark Rowley warned that the force is "a shrinking organisation" and faces losing around 1,700 officers, PCSOs and staff by the end of the year without more money from government.

"We're in an environment where money is tight," Ms Chiswick said. "We're having to make some difficult choices, and we know that technology and data can help us be more precise."

But Rebecca Vincent, Interim Director of Big Brother Watch, said there was a lack of parliamentary oversight and scrutiny of LFR.

"It's a massive privacy violation for people going about their daily life.

"There is no primary legislation governing this invasive technology. It means that police are being left to write their own rules."

She said it was unclear whether in future officers might be given access to other data, such as driving licences or passports.

Ms Chiswick said human rights and data protection laws, as well as guidance from the College of Policing helped police to understand how the technology should be used.

She said the watchlist was always intelligence led, and only included those who were wanted by police or the courts, or who were subject to court imposed conditions.

She told me that she believed there was "provision" for LFR to be used to search for vulnerable missing children, which might be considered less invasive to their privacy than making a public appeal, but that this had not yet been done.

Deputy commissioner of regulatory policy at the Information Commissioner's Office (ICO) Emily Keaney, said these cameras can help to prevent and detect crime, but added that "its use must be necessary, proportionate and meet expectations of fairness and accuracy".

She said they were working with the Met to review the safeguards in place and would be "closely monitoring" its use.

She added: "LFR is an evolving technology and, as our 2025 AI and biometrics strategy sets out, this is a strategic priority for the ICO.

"In 2019, we published guidance for police forces to support responsible governance and use of facial recognition technology.

"We'll continue to advise government on any proposed changes to the law, ensuring any future use of facial recognition technology remains proportionate and publicly trusted."

The Home Office said facial recognition was "a crucial tool to keep the public safe that can identify offenders more quickly and accurately, with many serious criminals already brought to justice through its use".

It added: "All police forces using this technology are required to comply with existing legislation on how and where it is used.

"We will set out our plans for the future use of facial recognition technology, in the coming months, including the legal framework and safeguards which will ensure it is properly used."