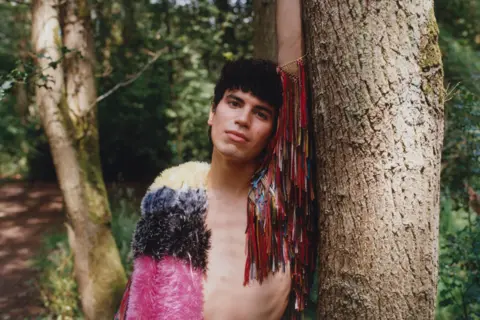

Jacob Alon: Free-spirited folk singer is one to watch

BBC

BBCJacob Alon's fingernails are something else.

Their left hand is beautifully manicured in sparkling purple and royal blue. On their right, the nails are like talons, sharpened to a menacing point.

The Scottish singer-songwriter nurtured those claws as a teenager, after discovering a dusty nylon-stringed guitar in a cupboard at their grandmother's house.

"I was always very clumsy with a plectrum," they say. "Growing out my nails changed entirely how I played the guitar."

"It probably started with trying to copy Nick Drake from YouTube. I suddenly felt intimately connected to the instrument.

"It feels like the guitar doesn't stop – it extends into my anatomy. That visceral connection is very special to me."

If you haven't heard of Jacob yet, it won't be long.

When they sing, time stops.

Tremulous vocals curl around the music like smoke, as the 24-year-old, who identifies as non-binary and uses they/them pronouns, traces poetic stories of romantic exploration and broken hearts.

As a writer, Jacob can be equally tender and ruthless. On Liquid Gold 25, named after a brand of poppers, they tackle the soul-crushing experience of queer dating apps like Grindr, singing: "This is where love comes to die."

The fragile melody of Confession, meanwhile, captures the crushing confusion Jacob felt when an ex-boyfriend denied their relationship had ever happened.

"It was such a deep rejection," they recall. "I was so confused that [they] couldn't come to terms with how they'd felt once, under all the layers of tragic, tragic shame that are imposed on you by the world."

Island Records

Island RecordsThat feeling of being trapped in limbo, controlled by a confusing dream-like logic, is a running theme of Jacob's debut album.

It's titled In Limerence, referring to a state of romantic infatuation that the singer's often trying to escape.

"There can be a darker side to dreams as a prison of fantasy – especially within relationships," they explain.

"Sometimes you cling to dreams so tightly that you lose sight of the magic of the real world."

On their debut single, Fairy In A Bottle, Jacob embodies that idea as a warning.

When you idolise your partner, you can't really know them, "because you've trapped them in this mythical version of themselves," they explain.

"You look past all of their flaws, and reasons it would never work."

The song is a realisation of that truth. "It's not your fault, it's my disease / And I must learn to set you free."

University drop-out

The musician learned those lessons the hard way – something that appears to have been a life-long pattern.

Raised in Fife, with its tawny beaches and sleepy fishing villages, a career in music was a distant dream.

"I remember a family member telling me, as a child, I'd be a poor fool to ever become a musician. And it stuck with me."

Instead, they took the academic route out, enrolling to study theoretical physics and medicine at Edinburgh University.

It didn't go well.

"I was so miserable," they recall. "I'd always found school really fulfilling and satisfying but university was really stifling. I realised that a life within academia didn't foster the same sense of curiosity about the universe that I'd felt going in."

It all came to a head when they crashed out on the floor of the university library, while desperately trying to cram for an exam.

"I remember sleeping between book shelves and the security guards kept waking me going, 'You can't sleep here, go home'.

"So I'd move to another room and they'd come and find me there too. I remember thinking, 'What am I doing with my life?'"

On a whim, they dropped out and moved to London to make music.

"It was chaotic," they say, suggesting that then-undiagnosed ADHD prompted the move.

"I had a breakdown and called my mum from the middle of street outside John Lewis, crying, because I didn't know where I was or where to go.

"But even though London didn't work out, I realised I was going to make music regardless, because it was the only thing that consistently brought my life meaning."

Island Records

Island RecordsSo they packed up their belongings, went back to Scotland, and started living in a van while touring Edinburgh's folk circuit.

"I'd have to sneak into swimming pools to have a shower," they recall, "but that was really a time of gestation and discovering my voice."

In the beginning, they mostly played covers – anything from Leonard Cohen to traditional Gaelic songs. But one night, in Edinburgh's cluttered and narrow Captain's Bar, a friend encouraged Jacob to play an original song they'd written for their younger sister, Stella.

"It's such a rowdy bar but people just stopped and fell silent and listened," Jacob recalls.

"Normally, I don't like it when everyone's looking at me – but it was such a powerful moment. It gave me a sense of self-belief that I'd never felt before."

Soon, Jacob was consumed by writing new material, pouring their feelings onto the page while scraping a living in a local coffee shop.

Intense and heartfelt, the songs charted a bumpy arrival into adulthood – forging a queer identity and figuring out what they wanted from life and relationships, while navigating a period where they were ostracised by their family.

"It was a very difficult time for my biological family," says Jacob, choosing their words carefully. "I was running away from a lot of pain. Fortunately, we're in a much better place now."

The naked vulnerability of those songs set Jacob apart. Within months, they'd gained a manager and signed to Island Records. Last November, with only one single to their name, they were booked to appear on Jools Holland.

On screen, they possessed a bewitching stillness, performing barefoot in a pair of golden feathered trousers like some sort of musical Icarus.

Under the surface, though, they were a bundle of nerves.

"I'd been playing a series of shows in the days before, and my voice had gone - but in the moment, something took over," they explain.

It's a moment that brought them back to childhood.

"I used to be a competitive swimmer when I was young, but I also have Tourette's.

"Sometimes, my tics would be unshakeable right up until the moment they said, 'On your marks'. Then, all of a sudden, this stillness would come over me."

"I was really worried it would crop up on Jools – because sometimes when I'm playing live, something will start ticking in my hand. But again, that stillness came."

It's hard to imagine a better metaphor for the way in which Jacob's music can soothe and heal. It possesses a magic that places them alongside folk nymphs like Nick Drake, Joni Mitchell, and Sandy Denny.

Acclaim is already incoming, and fast, but Jacob's learned the lesson of their own lyrics: This is a dream they won't get trapped in.

"A couple of billion years from now, the sun will expand, engulf the earth and maybe we'll be long gone – but there's a beautiful, optimistic nihilism in that," they explain.

"What's happening is happening now, so I just want to appreciate it, while I can feel the sun on my skin, and I can meet lovely people and converse and connect."