The WW2 aircrews who dropped secret agents into Europe

Chris Bullock handout

Chris Bullock handoutIn the last months of World War Two, aircrews from an Essex airfield were responsible for dropping secret agents and supplies into enemy occupied territory.

The men of 295 and 570 Squadrons, based at RAF Rivenhall near Chelmsford, were supporting Special Operations Executive (SOE), as well as supplying SAS units.

"Low flying skills were absolutely essential and they needed to find drop zones in the dark of night with minimal help on the ground and that took extreme confidence - and bravery, as they were on their own," said historian Chris Bullock.

Many of crews had also flown at D-Day and operations Market Garden and Varsity, surviving injuries and losing friends, he added.

Getty Images

Getty ImagesRivenhall's connection to SOE came as a surprise to Mr Bullock when he began researching the former airfield near his home 10 years ago.

"From October 1944, 295 and 570 Squadrons dropped SOE and SAS supplies into France, the Netherlands, Norway, Denmark and even one mission into Germany, while from February 1945, they also dropped agents into the Netherlands," he said.

"One well-publicised agent who dropped from Rivenhall was Jos Gemmeke; she escaped to the UK, carrying microfilm of V1 rocket sites after the failure at Arnhem, where she was trained by SOE, then parachuted back in March 1945."

Ms Gemmeke survived, was awarded one of the highest Dutch gallantry awards and given a military funeral when she died in 2010.

Prime Minister Winston Churchill ordered SOE to "set Europe ablaze" in June 1940, by supporting local resistance movements and conducting espionage and sabotage.

The bravery - and sacrifice - of "Churchill's secret army" has been remembered with films, books and TV series since the end of the war.

Getty Images

Getty ImagesMr Bullock, 56, who served in the 3rd Battalion, Parachute Regiment for 25 years, said the skills and courage of the air crews, making the drops behind enemy lines, has been underappreciated.

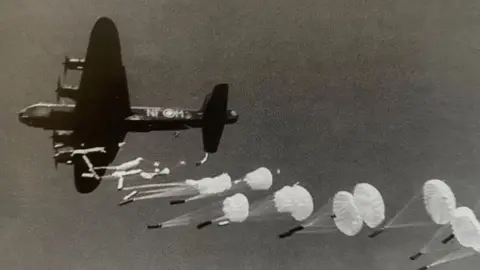

"They're flying extremely low, typically at 500 to 600 feet (152 to 182m) above ground level and there's an even greater skill to holding steady at such a low height," he said, and each plane was on a solo mission, without support.

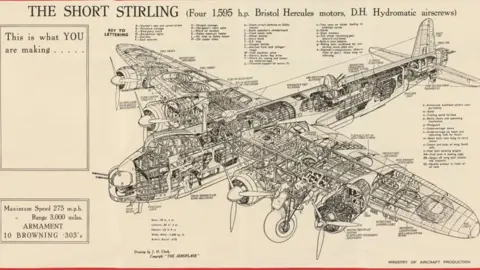

They could only fly when there was a full moon and, to ensure they carried as many supplies as possible, the Stirlings were stripped of their front and rear guns, leaving just one machine gun in the tail.

Getty Images

Getty ImagesNorway was the Rivenhall aircrews' initial destination in late 1944, flying in "horrific" conditions, said Mr Bullock.

"It was so cold inside the aircraft, and that made it difficult to fly, because once ice starts to form on an aircraft, it adds weight, and that makes it more difficult to control," he said.

A lot of the aircraft found themselves stalling and nearly crashing and on one early mission, Rivenhall lost its station commander, Wilfred Surplice.

Mr Bullock said: "The rest of the crew parachuted out, the plane crashed and he was killed - so imagine that for Rivenhall, your big boss goes out and doesn't come back."

Chris Bullock

Chris BullockHe has calculated about 40% of the squadrons' drops over Norway and the Netherlands were successful, with the right weather conditions and a reception committee ready and waiting for the drops on the ground.

Mr Bullock believes the missions required "a different kind of courage" to that shown by other World War Two RAF aircrew, "dropping these supplies behind German lines, right into the enemy's heart, without aircraft support and carrying out these missions on their own".

Follow Essex news on BBC Sounds, Facebook, Instagram and X.