Stalking protection orders very rarely used

BBC

BBCMeasures to stop stalking victims being harassed further are hardly being used, a campaigner has warned.

Stalking Protection Orders (SPOs) were introduced five years ago but a Freedom of Information request by the BBC found 1,439 SPOs were issued by the 40 forces who responded to the request.

Between 2020 and 2023 nearly 440,000 cases of stalking were recorded across the UK's 44 police forces.

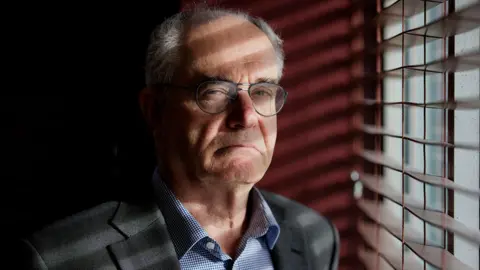

Clive Ruggles, whose 24-year-old daughter Alice was stalked and then murdered by her ex-boyfriend in Gateshead in 2016, said he was "getting increasingly exasperated" that SPOs were so little used five years after being introduced.

The Alice Ruggles Trust was part of the campaign to get the orders passed into law.

"This is what we fought for," Mr Ruggles said.

"SPOs provide a hugely important means of restraining perpetrators and protecting victims.

"They have to be used and have to be used properly."

PA Media

PA MediaAmy, a 37-year-old business owner from Middlesbrough whose surname the BBC has agreed not to use, was one of four people Cleveland Police applied for an order for in 2023.

Her ex-husband had tormented her after their 18-year marriage ended. He tracked her whereabouts through her watch, trolled her on social media and made tiny bank transfers to get her attention and keep him in her mind, she says.

When he ignored police warnings to leave Amy alone, the force suggested it apply for an SPO on her behalf.

She thought it was the answer to her prayers and that "finally he'd stop".

'Behaviour escalated'

SPOs were introduced in January 2020 and are civil orders that must be applied for by the police through the magistrates' courts on behalf of victims.

They prohibit activities such as entering certain locations or making contact.

They are designed to protect victims at the early stages of an investigation into alleged stalking and stop the kind of persistent harassment experienced by Amy.

Her ex-husband had managed to connect an old smart watch of hers to her phone's Bluetooth which meant he always knew where she was and had access to her emails.

"When our marriage ended his behaviour escalated," she said. "He would post about me on social media, get other people involved in messaging me.

"He'd transfer small amounts of money into my bank account - like 1p or 21p - just to harass me," Amy said.

"He would come into my shop and harass my employee."

The terms of Amy's SPO laid out that her ex-husband could not contact her by any means, or through a third party, and could not go to her home or work.

In November last year he was charged with breaching it by looking at her TikTok page, remanded into custody and, on 8 January, was found guilty at Teesside Magistrates' Court.

Amy initially found the terms of the order to be "too specific" meaning, unless her ex-husband breached the exact terms laid out in it, he would not be pursued.

She also said she was surprised by the amount of police officers that "didn't even understand what one [an SPO] was", and felt like people were not "properly educated" about them.

But, having now seen it do what it was meant to do, she said "when they work, they work".

Speaking exclusively to the BBC she said: "I just want freedom. I've lived a hectic and stressful life for the last few years and now I want to be free."

She had taken up self-defence classes and drove her dog to areas away from where she lives in a bid to protect herself from her ex-husband's stalking behaviour.

SPOs were part of the Stalking Protection Bill brought forward by former Totnes Liberal Democrat MP Sarah Wollaston in 2018 and which came into force in January 2020.

At the time Wollaston described stalking as an "insidious form of harassment".

Labour MP Jess Phillips, whose ministerial brief covers safeguarding and violence against women and girls, said the figures were "simply not good enough" and a "lot of work" was needed.

"With stalking, some of the legislation isn't the clearest it could be to make police able to work within the framework that exists," she said.

"So we've committed to look at exactly how the legislation lays out what stalking behaviours are."

Phillips, who has previously spoken about being a victim of stalking, said on one occasion the perpetrator "turned very, very violent towards not just me but other people around me".

She was pleased the government planned to change the law so SPOs could be used against someone in custody, she said.

"On one of the occasions, where someone had harassed and threatened to harm me and went to prison, he was able to continue that regime from prison."

Stalking and domestic abuse is a major concern for Cleveland Police.

For this reason it applied to be one of five forces who will pilot new Domestic Abuse Protection Notices.

The force has seen the second highest rate per population size of recorded offences for stalking in England and Wales.

Assistant Chief Constable Richard Baker said the force "should absolutely be doing more SPOs" but applying for them could "often lead into pages and pages" of paperwork.

"They're not simple to do for police officers," he said.

"That shouldn't be a barrier for victims. But a busy workload is one of the drawbacks of some of the civil orders available to us."

The Suzy Lamplugh Trust submitted a super complaint in 2022 about how police forces dealt with stalking.

The response was published in September following an investigation by His Majesty's Chief Inspector of Constabulary, senior representatives from the Independent Office of Police Conduct (IOPC), and the College of Policing.

It found "significant changes are needed" to improve the police's response to reports of stalking, including making SPOs simpler and easier to use.

The trust's head of policy and campaigns, Saskia Garner, said "stalking protection orders are being far too underused by police".

The charity wanted to see them used "as the first step to protecting a victims in the very earliest stages of reporting stalking", she said.

The National Police Chiefs Council said SPOs were a "valuable tool".

"We are working hard to drive best practice nationally across forces, ensuring orders are applied and utilised across the board, so the police response to stalking is more consistent and our service to victims is improved," it said.

Additional reporting by Lauren Woodhead, England Data Unit.

Follow BBC Tees on X, Facebook, Nextdoor and Instagram, external. Send your story ideas to [email protected].