There are signs Trump could be ready to retreat on tariffs

BBC

BBCOver the past week I have crossed a radically changing North America, from Arizona to Washington DC in the US and then on to Saskatchewan in Canada, witnessing clear evidence of the consequences of historic change in the way the world economy is run. Huge uncertainty means nobody really knows where it is headed.

The walk from the White House Rose Garden to the HQ of the International Monetary Fund (IMF) takes just 9 minutes. In the past few days, in this very short stroll, two very different worlds collided with each other.

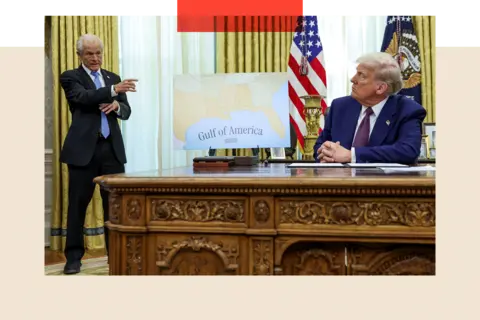

The former is the place where at the start of this month, with an extraordinary chart and questionable equation, President Trump took on the world with his so-called "reciprocal tariffs".

The latter is the place where just three weeks on from that, after rowback, market tumult, and confusion, the finance ministers of the entire world gathered to try to pick up the pieces, even as they were still rebounding off the ground.

At the IMF meetings that included gatherings of G7 and G20 members, something unique happened. The US representatives faced not open hostility, but exasperation, bewilderment and deep concern, from almost the entire rest of the world, for having sent the global economy back towards a crisis, just as it had finally emerged from four years of pandemic, war and energy shocks.

EPA-EFE/REX/Shutterstock

EPA-EFE/REX/ShutterstockThe concern was most acutely expressed by the East Asian countries, who had in early April been classed as "looters and pillagers" of American jobs because of the fact that these economies, many of them key allies of the US, export more goods to the US than the other way around.

The talk of the G7 was the quiet determined fury of the Japanese, who were said to feel betrayed by the US turn on trade, and whose confusion over what US trade negotiators actually wanted recently sparked a sell off of US government bonds. The finance minister Katsunobu Kato told the roundtable the US tariffs were "highly disappointing", hurting growth and destabilising markets.

I was reminded of the time at the IMF in 2022 when developing country finance ministers asked me if everything was OK in Britain during the mini budget crisis of Liz Truss' government. Then the UK was the source of fragility, trading like an emerging market, when its normal role was solving crises in those markets.

The bugle of retreat

In the face of febrile bond markets, this week the faint sound of the bugle of retreat on the US trade war got louder. A forest of olive branches seemed to be on offer from the US to get the Chinese to come back to the table to negotiate, from respect for their economic achievements to the offer of a deal to do a "beautiful rebalancing" of the world economy. It was a far cry from the claims of "looting and pillaging".

Yet a much hoped for meeting between US Treasury Secretary Scott Bessent and his Chinese counterpart did not materialise.

Most of the rest of the world leaving their meetings with Bessent are reporting back an assumption that the US is edging away from what it cannot acknowledge was overreach.

Reuters

ReutersAnd there is a widespread view that there is no need for countries to retaliate, when the CEOs of Walmart and Target are telling the President privately that there will be empty shelves from early May.

The collapse in container traffic from China to the port of Los Angeles - the main artery of the world economy for the first quarter of the 21st century - is the one to watch. The IMF's boffins say they can start to see the impact from space as satellites track fewer, increasingly empty ships leaving China's ports. Of course this will be denied by the US.

West Wing farce

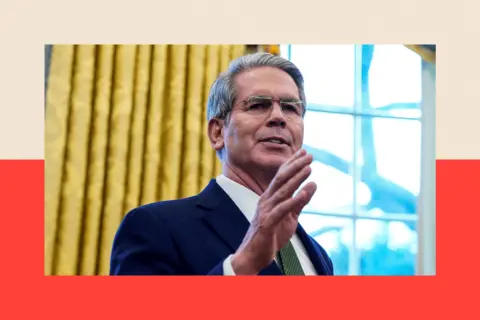

It is true that there was far more relative calm at the end of the IMF Meetings compared to the beginning. Why? Because the US Treasury Secretary Scott Bessent has seized control of the tariff agenda and has almost single-handedly calmed markets and the rest of the world.

Financial diplomats put down the Bessent ascendancy and the critical 90 day pause in the so-called "reciprocal" tariffs to some farcical West Wing antics.

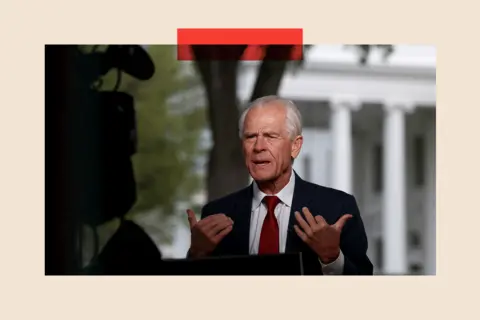

The story goes Bessent was able to get the ear of Trump regarding the bond market damage from his tariffs, only after a separate White House economic adviser managed to use the bait of a fake meeting to lure away the hardline tariff hawk and author of the infamous reciprocal tariff equation Pete Navarro from patrolling the Oval Office.

Reuters

ReutersWall Street bosses are thought to have suggested that only by firing Navarro, can some semblance of normality return. Insiders suggest that Trump will never get rid of his trade adviser, as he served time in jail after the January 6 riots in support of the President.

At best this sounds like the future of the world economy and all our livelihoods played out like a real time Hilary Mantel novel about the court of Trump. At worst it is leading to financiers and Governments starting to think the unthinkable about how much further the US or the rest of the world might go and currently, the uncertainty about everything is more concerning than the direct impact of the tariffs.

A nightmarish scenario

And that uncertainty is prompting some fairly wild theories about what might come next.

At times of acute global financial stress, "swap lines" between central banks exist to preserve financial stability, making sure there is a constant supply of US dollars.

But now some of the world's central banks have started to game out what might happen if the US chose to use its dollar "swap lines" to the rest of the world as a form of diplomatic leverage or even a weapon.

Is it inconceivable that the US might deny them or veto the Federal Reserve handing them out? One just has to assume it is inconceivable, because in many instances there is no way to mitigate it. But the nightmarish scenario for the world financial system, however unlikely, is now not wholly implausible.

A little less unlikely perhaps is the idea that those countries with a trade surplus with the US could help fund the US with an effective tax on their holdings of US government debt. Some of these ideas have been floated in speeches and papers by US government advisers.

Reuters

ReutersIn this atmosphere, worrying but incorrect ideas can start to infect confidence. For example, there was a "whodunnit" about significant selling of US Government debt just after the original tariff reveal.

Some speculated it was China. But Tokyo currently happens to be the biggest overall creditor to the US. Was this Japanese selling that helped make the case to Trump for the tariff pause, an almost deliberate diplomatic tactic? Two very well connected officials suggested this scenario to me, which shows the febrility right now, even though it seems implausible.

No one crawling

While Bessent commanded the weekend airwaves in the US having assumed control of this process, it was still quite something to see him sending the message that "Investors need to know that the U.S. government bond market is the safest and soundest in the world". If you have to say it…

Another significant finance minister told me of his global counterparts that "no one was crawling to the Americans" given the unbeatable effectiveness of the US having to negotiate with its own bond market.

Amid the uncertainty, no one seems to know if the "baseline" universal tariff of 10% is even negotiable. President Trump's message that tariff revenue could be sufficient to "completely eliminate" income taxes for "many people" would rather suggest that it will stay.

Reuters

Reuters"It depends on who you talk to on which day of week… I've heard three different positions articulated on the baseline, one by the White House, one by the Commerce Dept, and one by a US Trade representative," said one senior G7 official. "Do you know what the final outcome will be? Whatever the president wants at that moment, shaped by industrial, market and political issues," I was told.

Consistent UK diplomacy

This is of particular interest to the UK, because the baseline bites the UK hard. Alongside big tariffs on cars which are our biggest goods export and likely further ones on pharmaceuticals, our second most important export, the US hit to the UK appears inexplicable when by the White House's own creative definition of "trade cheating" - running a goods surplus - the US is actually slightly "cheating" the UK.

I put this point to the Chancellor several times over two interviews in Washington. She diplomatically rejected that suggestion.

But eventually right at the end of our last interview, strolling around the famous reflecting pool in between the Lincoln Memorial and the Washington Monument, she volunteered something rather telling of the changing world. "I understand why there's so much focus on our trading relationship with the US but actually our trading relationship with Europe is arguably even more important, because they're our nearest neighbours and trading partners," she told me. It caused a bit of a fuss back home, but it was not an off the cuff gaffe.

That's because concessions to the US on food standards are off limits for domestic political reasons. This appears to have been accepted by the Americans after consistent UK diplomacy, as the focus remains on a technology prosperity deal. It seems pretty clear now that the UK is going to push ahead with a "high ambition high alignment" deal with the European Union. And word had got out here among finance ministers.

Reuters

ReutersA very senior international official used the example of the UK-EU rapprochement as an example of the rest of the world coordinating and "doing its homework" as a response to US unreliability. "Brexit was a bitter divorce, but now I see you are dating again," I was told privately.

There was also some relief that the US remained engaged with the World Bank and IMF. The Project 2025 plan that was published in April 2023 by the think tank The Heritage Foundation in anticipation of a second Trump presidency envisaged the US leaving those international organisations, and the Governor of the Bank of England recently expressed his concerns to me.

Bessent used the meetings to confirm US commitment to the Bank and the Fund, albeit with a return to their core functions and away from considerations of social issues and the environment. The Europeans counted that as a win.

A grand battle?

But a bigger canvas remains. Will the US use this trade war in order to try to corral the rest of the world on to its side in a grand battle with China? It seems astonishing to have annoyed allies so significantly and fundamentally if this was the strategic point of all this. A test case here is Spain, which faces 20% tariffs as an EU member state.

Spanish Prime Minister Pedro Sánchez met President Xi in Beijing a fortnight ago. Spain's booming economy (the fastest growing advanced economy last year - and forecast to be again this year) is the only one to be upgraded by the IMF. It is built on green energy, access to foreign labour, tourism and significant investment and technology transfer from China. The US took a dim view of the visit and held a "frank" discussion with its finance minister Carlos Cuerpo.

He appeared rather unmoved by all this, telling me at the Semafor World Economy Summit in DC: "There's a huge trade deficit with China, and we need to correct that by opening up to China, by also attracting Chinese investment, of course, within an overall economic security umbrella. And that can only be done by engaging and actually talking to the Chinese authorities".

EPA-EFE/REX/Shutterstock

EPA-EFE/REX/ShutterstockSpain has secured notable Chinese electric vehicle factory investment and technology transfer. The US doesn't like it. But if the US wanted to persuade the Spanish and EU of its reliable long term allyship against China, it is difficult to see the strategy in the past month's tariff accusations and chaos.

Whoever wins in Canada's election will bring that G7 economy firmly back into this globally transformative debate. Could the newly elected Canadian PM start a full fat negotiation with the UK too? And then he will chair the G7 Summit in Canada in June as President Trump's 90 day deadline expires. It is presumed Donald Trump will travel to Alberta, to the country he claims should be part of his own.

There is a path to trade peace, calm and deescalation. But it could get much worse too. This is a critical few weeks for the world economy.

BBC InDepth is the home on the website and app for the best analysis, with fresh perspectives that challenge assumptions and deep reporting on the biggest issues of the day. And we showcase thought-provoking content from across BBC Sounds and iPlayer too. You can send us your feedback on the InDepth section by clicking on the button below.