Her dad never spoke about his life in Berlin - now she knows why

Sara Davidmann

Sara DavidmannSara Davidmann always knew her father Manfred had arrived in Britain having fled Nazi Germany as a 14-year-old boy.

However, his life growing up as a Jew in Berlin before his escape with his 17-year-old sister Susi in 1939 on the Kindertransport had remained a mystery.

"My father was never able to talk about what had happened to him at all," the London-based artist explains.

"When he was alive, he was a very difficult man to get close to... It was just a chapter of his life that he felt he had to internalise."

Sara Davidmann

Sara DavidmannFollowing his death a decade ago, Sara set out to discover what had happened to her dad.

"We all grew up knowing that there was more, but not what it was and it was just something you didn't ask about."

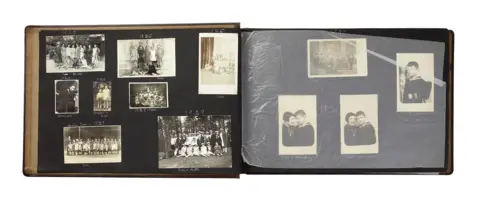

The catalyst for this work was the discovery of a family photo album featuring images covering a period between 1910 and 1988, that had been put together across decades by her late aunt Susi.

Containing carefully annotated images, including many of her father, it revealed numerous relations who Sara had never heard of before.

"It was just amazing because there was this family in Germany and a lot of them were in Berlin that I knew nothing about," she says.

However, along with scenes of family outings and seaside holidays, the images suggested something much darker as Sara realised many of those who were pictured before World War Two didn't appear again later in the book.

Sara Davidmann

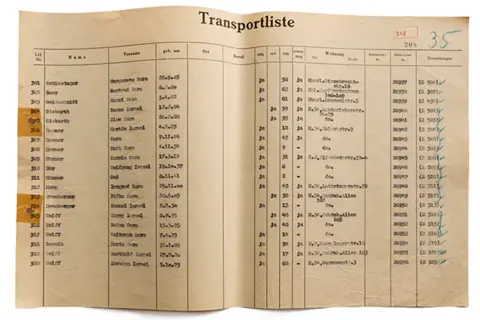

Sara DavidmannInvestigating further, she visited the Wiener Holocaust Library in Bloomsbury, and the Arolsen Archives in Germany, where researchers helped uncover more than 130 historical documents related to her family.

These revealed both tragic and remarkable stories about those missing from the photos.

For her great grandmother Dorothea and great aunt Marta, Nazi transportation documents showed they had been taken to concentration camps in Auschwitz and Theresienstadt, where neither would be heard of again.

"To be holding in my hand the same documents that were held by people who were responsible for putting them on this transportation and their deaths, I mean, that was just so chilling," the artist says.

Sara Davidmann

Sara DavidmannOther relations were found to have undertaken incredible journeys to survive the war.

"I had a great aunt Rosa who I wish I'd known - she managed to escape to France, she was held in two different camps and managed to escape."

Some family members were revealed to have fled to Shanghai in China and others to Israel.

"And then my grandmother, Paulina, she survived the war hiding in Berlin using false documents," notes Sara.

With none of those family members still alive to learn from, she set out to discover more about what it was like for a Jewish person in Germany after Adolf Hitler came to power - a subject she says she previously had an "aversion to" studying given her own father's refusal to speak about it.

"So I then learnt from 1933 onwards over 400 antisemitic laws were passed, which gradually took away everything from Jewish people living in Berlin - it affected all aspects of their lives," she says.

"It gave me a real insight into my father's experiences when he was growing up in Berlin as a young Jewish boy, and also insights into the lives and experiences of all these other members of my family."

Sara Davidmann

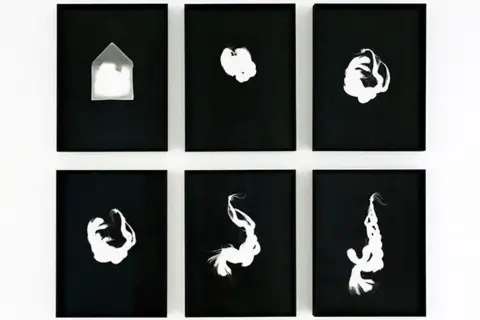

Sara DavidmannAt the same time as carrying out this work, Sara began creating artworks as a reaction to learning about the fates of a family which had been torn apart.

These she describes as being "quite visceral" with items like hair, blood and burnt material being used to often reflect the impact of those antisemitic laws the Nazis had introduced.

One, called My Name is Sara, features a series of photograms displaying an unravelling plait of her own hair which had been cut off when she was a child.

She says the title of the work was inspired not only by her own name but also a law passed by the Nazis which forced German Jews to adopt an extra name to make them stand out - Israel for men and Sara for women - as the transport documents revealed had happened to her relations Marta and Dorothea.

Sara Davidmann

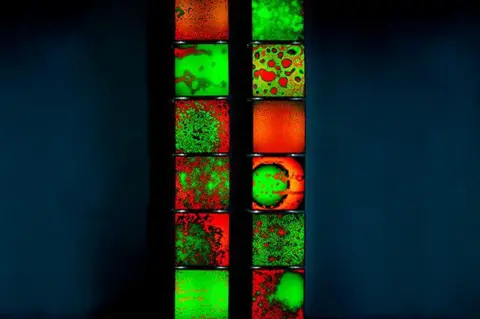

Sara DavidmannAnother work features a series of light boxes which display microscopic blood samples taken from her living family members that have been coloured red and green.

These, she explains, began as a response to the Nuremberg race laws, which excluded German Jews from Reich citizenship and prohibited Jewish people from marrying German citizens for fear "that Jewish blood would contaminate German blood and the purity of the German race would be depleted".

The light boxes are therefore her defiant response as it "really shows the survival of my family", she says.

Sara Davidmann

Sara DavidmannThe works formed an exhibition at the Four Corners Gallery in Bethnal Green held in 2021, as well as a book called Mischling 1.

For Holocaust Memorial Day this year, Sara is taking part in an "in conversation" event at the Wiener Holocaust Library where she will be speaking about her family and her work.

She says discovering the impact of the Holocaust on them "has given me a connection to this history and my father".

She also thinks it's essential to speak about what happened and mark Holocaust Memorial Day, with its message to remember the millions of people killed under Nazi persecution, as well as those during more recent genocides like in Cambodia and Rwanda.

"When I was going to different Holocaust museums and memorials around the world, each time the phrase 'never again' was either written on the wall or came up in some documentation," Sara says.

"It really is a very important day."

Listen to the best of BBC Radio London on Sounds and follow BBC London on Facebook, X and Instagram. Send your story ideas to [email protected]