Planet-warming gas levels rose more than ever in 2024

AFP

AFPLevels of the most significant planet-warming gas in our atmosphere rose more quickly than ever previously recorded last year, scientists say, leaving a key global climate target hanging by a thread.

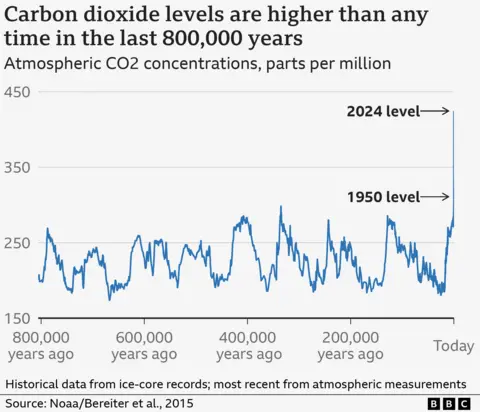

Concentrations of carbon dioxide (CO2) are now more than 50% higher than before humans started burning large amounts of fossil fuels.

Last year, fossil fuel emissions were at record highs, while the natural world struggled to absorb as much CO2 due to factors including wildfires and drought, so more accumulated in the atmosphere.

The rapid increase in CO2 is "incompatible" with the international pledge to try to limit global warming to 1.5C above pre-industrial levels, the Met Office says.

This was the ambitious goal agreed by nearly 200 countries at a landmark UN meeting in Paris in 2015, with the hope of avoiding some of the worst impacts of climate change.

Last week it was confirmed that 2024 was the hottest year on record, and the first calendar year in which annual average temperatures were higher than 1.5C above pre-industrial levels.

This did not break the Paris goal, which refers to a longer-term average over decades, but continued increases to atmospheric CO2 effectively consign the world to doing so.

"Limiting global warming to 1.5C would require the CO2 rise to be slowing, but in reality the opposite is happening," says Richard Betts of the Met Office.

The long-term CO2 increase is unquestionably due to human activities, mainly through burning coal, oil and gas, and cutting down forests.

Records of the Earth's climate in the distant past from ice cores and marine sediments show that CO2 levels are currently at their highest in at least two million years, according to the UN.

But the rise varies from year to year, thanks to differences in how the natural world absorbs carbon, as well as fluctuations in humanity's emissions.

Last year, CO2 emissions from fossil fuels reached new highs, according to preliminary data from the Global Carbon Project team.

There were also the effects of the natural El Niño phenomenon - where surface waters in the eastern tropical Pacific Ocean become unusually warm, affecting weather patterns.

The natural world has absorbed roughly half of humanity's CO2 emissions, for example through extra plant growth and more of the gas being dissolved in the ocean.

But that extra blast of heat from El Niño against the background of climate change meant natural carbon sinks on land did not take up as much CO2 as usual last year.

Rampant wildfires, including in regions not usually affected by El Niño, also released extra CO2.

"Even without the boost from El Niño last year, the CO2 rise driven by fossil fuel burning and deforestation would now be outpacing the [UN climate body] IPCC's 1.5C scenarios," says Prof Betts.

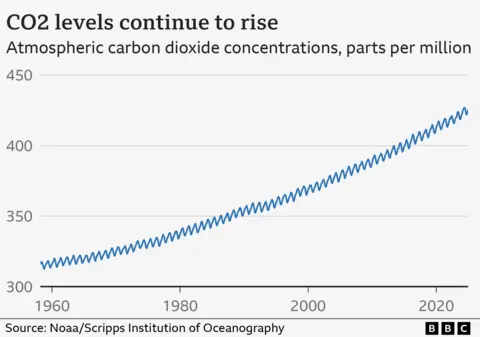

These factors meant that between 2023 and 2024 CO2 levels increased by nearly 3.6 parts per million (ppm) molecules of air to a new high of more than 424ppm.

This is a record yearly increase since atmospheric measurements were first taken at the remote Mauna Loa research station in Hawaii in 1958. Perched high on the side of a volcano in the Pacific Ocean, the station's remote location away from major pollution sources makes it ideally suited to monitoring global CO2 levels.

"These latest results further confirm that we are moving into uncharted territory faster than ever as the rise continues to accelerate," says Prof Ralph Keeling, who leads the measurement programme at the Scripps Institution of Oceanography in the US.

AFP

AFPThe record increase adds to concerns that the natural world may become less able to absorb planet-warming gases in the long-term.

The Arctic tundra is being transformed into an overall source of CO2, thanks to warming and frequent fires, according to the US science group NOAA.

The ability of the Amazon rainforest to absorb CO2 is also being hit by drought, wildfires and deliberate deforestation.

"It's an open question, but it's something we need to keep a close eye on and look at very carefully," Prof Betts tells the BBC.

The Met Office predicts the increase in CO2 concentration in 2025 will be less extreme than 2024, but still significantly off-track to meet the 1.5C target.

La Niña conditions – where surface waters in the eastern tropical Pacific Ocean are cooler than normal - have replaced El Niño, which tends to allow the natural world to take up more CO2.

"While there may be a temporary respite with slightly cooler temperatures, warming will resume because CO2 is still building up in the atmosphere," Prof Betts says.

Sign up for our Future Earth newsletter to get exclusive insight on the latest climate and environment news from the BBC's Climate Editor Justin Rowlatt, delivered to your inbox every week. Outside the UK? Sign up to our international newsletter here.