Here are the sticking points as House holdouts stall Trump's budget bill

Donald Trump's massive tax and spending budget bill has returned to the US House of Representatives - as the clock ticks down to the president's 4 July deadline for lawmakers to present him with a final version that can be signed into law.

The bill narrowly cleared the Senate, or upper chamber of Congress, on Tuesday. Vice-President JD Vance cast a tie-breaking vote after more than 24 hours of debate and resistance from some Republican senators.

It has so far proven equally tricky for Trump's allies to pass the bill through the House, where Speaker Mike Johnson's hopes of holding a vote on Wednesday appear to be thinning out.

Members of Congress had emptied from the House floor by the afternoon, after it became clear there weren't even enough votes for the bill to pass the rule that allows the legislation to be brought to the floor, typically an easy procedural task.

The House, or lower chamber, approved an earlier version of the bill in May with a margin of just one vote, and this bill, with new amendments that have frustrated some Republicans, must now be reconciled with the Senate version.

Both chambers are controlled by Trump's Republicans, but within the party several factions are fighting over key policies in the lengthy legislation.

The president has been very involved in attempting to persuade the holdouts and held several meetings at the White House on Wednesday in hopes of winning them over.

Ralph Norman, a House Republican from South Carolina, attended one of the meetings but wasn't persuaded.

"There won't be any vote until we can satisfy everybody," he said, adding he believes there are about 25 other Republicans who are currently opposed to it. The chamber can only lose about three Republicans to pass the measure.

"I got problems with this bill," he said. "I got trouble with all of it."

Sticking points include the question of how much the bill will add to the US national deficit, and how deeply it will cut healthcare and other social programmes.

During previous signs of rebellion against Trump at Congress, Republican lawmakers have ultimately fallen in line.

What is at stake this time is the defining piece of legislation for Trump's second term. Here are the factions standing in its way.

The deficit hawks

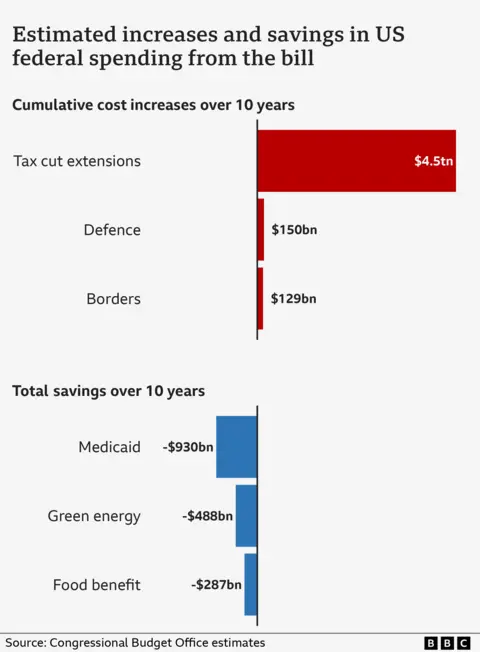

The Congressional Budget Office (CBO) estimated that the version of the bill that was passed on Tuesday by the Senate could add $3.3tn (£2.4tn) to the US national deficit over the next 10 years. That compares with $2.8tn that could be added by the earlier version that was narrowly passed by the House.

The deficit means the difference between what the US government spends and the revenue it receives.

This outraged the fiscal hawks in the conservative House Freedom Caucus, who have threatened to tank the bill.

Many of them are echoing claims made by Elon Musk, Trump's former adviser and campaign donor, who has repeatedly lashed out at lawmakers for considering a bill that will ultimately add to US national debt.

Shortly after the Senate passed the bill, Texas congressman Chip Roy, of the ultraconservative House Freedom Caucus, was quick to signal his frustration.

He said the odds of meeting Trump's 4 July deadline had lengthened.

Getty Images

Getty ImagesFreedom Caucus chairman Andy Harris of Tennessee told Fox News that Musk was right to say the US cannot sustain these deficits. "He understands finances, he understands debts and deficits, and we have to make further progress."

On Tuesday, Conservative congressman Andy Ogles went as far as to file an amendment that would completely replace the Senate version of the bill, which he called a "dud", with the original House-approved one.

Ohio Republican Warren Davison posted on X: "Promising someone else will cut spending in the future does not cut spending."

The Medicaid guardians

Representatives from poorer districts are worried about the Senate version of the bill harming their constituents, which could also hurt them at the polls in 2026.

According to the Hill, six Republicans were planning to vote down the bill due to concerns about cuts to key provisions, including cuts to medical coverage.

Some of the critical Republicans have attacked the Senate's more aggressive cuts to Medicaid, the healthcare programme relied upon by millions of low-income Americans.

"I've been clear from the start that I will not support a final reconciliation bill that makes harmful cuts to Medicaid, puts critical funding at risk, or threatens the stability of healthcare providers," said congressman David Valadao, who represents a swing district in California.

This echoes the criticism of opposition House Democrats, whose leader, Hakeem Jeffries, posted a picture of himself on Wednesday to Instagram, holding a baseball bat and vowing to "keep the pressure on Trump's One Big Ugly Bill".

Other Republicans have signalled a willingness to compromise. Randy Fine, from Florida, told the BBC he had frustrations with the Senate version of the bill, but that he would vote it through the House because "we can't let the perfect be the enemy of the good".

House Republicans had wrestled over how much to cut Medicaid and food subsidies in the initial version their chamber passed. They needed the bill to reduce spending, in order to offset lost revenue from the tax cuts contained in the legislation.

The Senate made steeper cuts to both areas in the version passed on Tuesday.

Changes to Medicaid and the Affordable Care Act (better known as Obamacare) in the Senate's bill would see roughly 12 million Americans lose health insurance by 2034, according to a CBO report published on Saturday.

Under the version originally passed by the House, a smaller number of 11 million Americans would have had their coverage stripped, according to the CBO.

Hakeem Jeffries/Instagram

Hakeem Jeffries/InstagramThe state tax (Salt) objectors

The bill also deals with the question of how much taxpayers can deduct from the amount they pay in federal taxes, based on how much they pay in state and local taxes (Salt). This, too, has become a controversial issue.

There is currently a $10,000 cap, which expires this year. Both the Senate and House have approved increasing this to $40,000.

But in the Senate-approved version, the cap would return to $10,000 after five years. This change could pose a problem for some House Republicans.