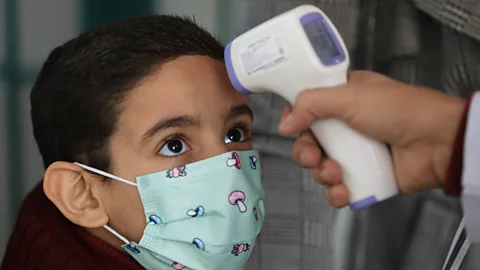

The pandemic generation: How Covid-19 has left a long-term mark on children

Getty Images

Getty ImagesThe stress and isolation of the pandemic has left social and emotional scars that are already being seen in children, but scientists also predict there could be huge economic costs due to disrupted education.

For US pre-school teacher Rebekah Underwood, there is something different about the class of 2025. She's noticed that the children she teaches – aged between five and six years old – are physically more cautious than the group who attended the pre-school in Santa Monica in California before the pandemic.

"Many kids are not able to roll, not able to jump on two feet, they are very hesitant to climb," she says. She wonders if it has something to do with a lack of outdoor exploration that happened when these children were toddlers. They are among the group who were babies when Covid-19 hit.

In March 2020, schools around the world began to suddenly close and life for the 2.2 billion children and young people around the world took a dramatic change. Whole families found themselves stuck at home, venturing outside only for short, allotted periods while children of school age were taught by their parents or learned via a screen.

It meant that children lost the rhythm of everyday life – the opportunity to attend clubs, play sports, practice hobbies were replaced with activities at home, crafts and television. Many also missed out on milestones like school dances, parties and graduations. In some places, students wouldn't be back, mixing with their peers, for a year. The average school was closed for 5.5 months, but some were shuttered much longer. Combine that with the stress of the pandemic and of their parents in an unprecedented situation, it triggered widespread speculation about what impact the Covid-19 pandemic would have on the generation of young people experiencing it.

Childhood experiences, after all, tend to have an outsized effect on life trajectories because they can alter brain development, behaviour and overall wellbeing.

Underwood and her colleagues saw a difference in the children they were teaching almost as soon as schools reopened in 2021. This year, which includes children who were only just being born as the pandemic hit, they are seeing some improvements on previous years.

The children in Underwood's young classes, for example, are easily overstimulated. The school where she works had to suspend music classes two years ago, because instruments in the classroom were simply too much for the young children to handle – the raucous noise, both joyful and chaotic, made them very upset. "Half the class sat outside because they were so overstimulated," Underwood says. "Especially in a hands-on classroom, it's hard to manage." She wonders if these children who didn't experience music groups or playgrounds when they were little now struggle with loud, chaotic environments. This year, they have slowly started reintroducing music into the curriculum.

Five years after Covid-19 first began spreading around the world, triggering widespread lockdowns, researchers are starting to unravel the effect of the abrupt societal changes may have had on children. The pandemic has left its mark on their behaviour, mental health, social skills and their education. But how deep those scars may run and their effects in the long term may only become clear in the decades to come.

As a baby, everything is new: every visit to the park, every smell inside a grocery store, every touch of a soft pet. So what happens when a baby doesn't experience a rich tableau of life experience?

In England, the Born in Covid Year Core Lockdown Effects (Bicycle) study is trying to tease apart the role of lockdowns on children born between March and June 2020.

"We were really concerned during Covid that children were getting a very unusual experience," says Lucy Henry, a professor of speech and language at City St George's, University of London.

The study follows two groups of 200 children born before the pandemic, during the lockdowns of 2020 and after they were lifted in 2021, focusing on language skills and executive functioning at age four. The researchers play simple games with the children – including one where they have to click when a cat appears on a screen. The aim is to "splat the cat" but avoid clicking when they see a dog – a measure of inhibition and other executive functions.

Their preliminary findings are due to be published later this year, but the researchers say their results seem to indicate that children who were babies during the pandemic have fewer words and may struggle more with higher-level thinking skills. "The overall picture across the evidence is that communication seems to be something that might have been impacted," says Nicola Botting, a developmental psychologist at City St George's, University of London, who is the co-lead of the study.

The researchers are hoping their work will help them understand the reasons for this delay, although they speculate that the lack of social opportunity in the first year of life may have had an outsized impact on children's development. Babies born in the strictest of lockdowns didn't get the more public social communication opportunities, like waving at people, going on a swing, seeing different faces talking, or hearing different voices talking.

"We know from a wide body of research, those early few months are super important in terms of learning the foundations of social communication," says Botting. "Although babies look like they're doing nothing, they are doing things, and one of those things is taking in diverse social opportunities."

Getty Images

Getty ImagesWhile the longer-term implications of those developmental delays will take time to understand – and it may be possible that such young children can catch up relatively quickly – one of the main areas of research on the effects of the pandemic on youngsters has been on education.

An estimated 1.6 billion students in more than 190 countries had their education disrupted by the pandemic. When schools closed, large portions of learning passed to parents who home-schooled their children alongside remote learning sessions over the internet. Children without access to computers or reliable internet connections inevitably suffered more.

In 2023, the National Academies of Sciences, Engineering and Medicine in the US published a wide-ranging report on the effects that Covid-19 pandemic had taken on children, finding that "across all measures of school engagement and learning outcomes, students appear to be worse off" than they would have been without the pandemic. The effects are particularly pronounced among those from low-income families and marginalised communities, a pattern that crops up repeatedly when looking at many aspects of how Covid-19 has affected children.

Chillingly, the report concludes that the losses in learning that occurred during the pandemic era could have lasting economic implications once these children reach adulthood.

One recent study published in January 2025 tried to quantify the learning loss, using global test score data. They found that mathematics scores declined an average of 14% – roughly equal to seven months of learning for a student.

Some groups – including students in schools that faced relatively longer closures, boys, immigrants, and disadvantaged students – fared even worse. And distance learning, where students logged onto screens for class, didn't seem to do much to stem the tide of learning loss. In the end, they say, these learning losses could translate to earnings losses and could cost this generation of students trillions of dollars.

"The gaps are there, and they are not disappearing," says Maciej Jakubowski, an education researcher at the University of Warsaw in Poland, who led the study. The findings match those from other studies. Across Europe, for example, children lost the equivalent of one-to-three months'-worth of learning, with some countries such as Poland and Greece seeing three times that level. Even more significant effects were found in countries including Brazil, Mexico, South Africa and the United states, with more ground being lost in maths and science than other subjects. Another major review of 42 studies across 15 different countries over a year and a half of the pandemic estimated that pupils lost a third of a school year's worth of learning due to the shutdowns.

Getty Images

Getty ImagesThese deficits also persisted as the pandemic progressed, with no clear catch up even after schools began to reopen, says Bastian Betthäuser, who studies social inequalities at the University of Oxford in the UK and led that review. "We saw that those early learning deficits were very sticky," says Betthäuser. "That didn't grow much worse as the pandemic continued, but we didn't at that point see a clear trend towards recovery."

The results were also similar for primary and secondary school students. That came as a bit of a surprise, as the researchers thought the deficits would be greater for younger students, who were less likely to be able to learn on their own. Betthäuser says that could be because school closures were longer and more intense for older students – so they ended up being out of school for longer and missing more material.

Since the pandemic, many schools have tried to catch up students through accelerated learning, but with varying success. But Betthäuser says there are glimmers of hope – evidence from the UK and the US shows there has been some recovery to those large learning deficits – but that it hasn't been complete. "This recovery tends to be faster for kids from more advantaged backgrounds, meaning that the achievement gaps between kids from different socioeconomic backgrounds remain very large, at times even larger than they were before the pandemic," adds Betthäuser.

The effects of this sort of unfinished learning can linger, manifesting into hard economic costs to society, says Jakubowski.

For some countries, such as Poland, the learning losses translate into a decline in economic growth of 0.35%. An analysis by management consultant McKinsey estimates that unfinished learning by students during the pandemic could see them earn tens of thousands of dollars less over their lifetime than those whose studies were uninterrupted. This could hurt the US economy by $128bn-$188bn (£94.6bn to £139bn) every year once the students of 2020 enter the workforce.

"That's a huge economic impact," says Jakubowski.

Jakubowski says that there are targeted interventions that can help to address learning gaps, such as small-group instruction, or tutoring on specific topics, although it is an expensive solution.

The long-term cost to society may go beyond education though. The Covid-19 lockdowns led to concerns about how children's physical health may have altered during the pandemic. One study in the UK found that obesity among young children aged between 10 and 11 years old increased during the pandemic, and have persisted. This, the researchers estimate, amounts to an additional 56,000 children being obese. This is likely to be due to changes in eating behaviour and physical activity that occurred in many countries during the pandemic and have perhaps continued. In the long term, this could cost UK society an estimated £8.7bn, the researchers say.

Getty Images

Getty ImagesBut while the pandemic led to a sudden shock to children's lives and education, it also exacerbated trends that were already taking place prior to the appearance of Covid-19.

Judith Perrigo, an education researcher at the University of California, Los Angeles, had been watching scores in reading and maths slowly decline in the US for years. Perrigo leads a long-term study of kindergarteners that has been going on for 14 years. The study asks their teachers to give a score on each student's physical health and well-being; social competence; emotional maturity; language and cognitive development; and communication and general knowledge.

But she and her colleagues found that the pandemic led to an even sharper drop in language, cognitive and social competence skills. The study was unique in that the researchers had been collecting the same data for over a decade, allowing them to see the impact of a universal shock like Covid-19 over the population and over time.

"The story is that the Covid pandemic hurt children developmentally," she says, although she says her study shows the downward trajectory was already underway when it hit.

Perrigo and her colleagues expected to see declines in all areas the teachers were assessing, but instead, they found that three out of the five dropped – language and cognitive skills, communication skills and social competence. Physical health stayed the same – possibly because there was so much emphasis on public health during the time that it made it easier to stay healthy, or the time at home during the first lockdowns saw children spend more time outdoors when they were allowed.

Perhaps surprisingly, the researchers also saw children's scores for emotional maturity improved during the pandemic. While that may seem counterintuitive at first, Perrigo says, there is a body of research that connects the threads between adversity and emotional maturity.

"When children experience adversities, this could be parental divorce, it can be neighborhood violence, they experience emotional maturity that comes along with those adversities," she says. "During Covid, there was nowhere to go. The news was on. We saw fatality counts every day. Children were exposed to a lot of big, complicated topics. And so their emotional maturity scores actually increased."

Whether this will help better equip this generation for the trials they face later in life remains to be seen. But the stress of the pandemic may have left other marks on the mental health of children and adolescents – with many studies revealing elevating levels of anxiety, depression, anger and irritability during the lockdowns. Children also showed increased signs of internalisation and behavioural problems due to the long periods of confinement. Those who did more exercise, had access to entertainment and had positive family relationships tended to fare better. And perhaps unsurprisingly, the more stressed parents were by the lockdowns, the more volatile their children's wellbeing tended to be.

There is also evidence that some of the problems continued after schools and universities reopened. One study in China found children tended to be less prosocial, or willing to act in ways that benefited others.

Getty Images

Getty ImagesTandy Parks, a social worker who leads parenting groups in Los Angeles, says she finds families still managing the fallout of disruptions to learning and social connections during the pandemic. Many children she works with are slow to separate from parents and gain a sense of independence. "I get calls from parents of kids four to seven, and it's almost the conversations that I used to have with people with 2.5-year-olds," she says. Parents are struggling with setting appropriate limits and communicating clearly with children, while even developmental milestones such as potty training occurring on a much slower timeline, Parks says.

There are hopes, however, that by researching how children fared during and after the pandemic, it may also be possible to identify strategies to support them in future. "We hope that some of what we find isn't just applicable in case there's another pandemic, but also speaks to limited social opportunities of different kinds," including growing up as part of groups that may be isolated for cultural or other reasons, says Henry. "So there's a sort of a breadth, as well as a longitudinal viewpoint there."

UCLA's Perrigo warns that more aid is needed to help young people – around the world – who have faced such an abrupt change to their lives. Unless policy makers, parents and teachers start to concentrate efforts and use approaches shown by science to improve wellbeing, the trends will continue to worsen over time, she says. "Those trajectories are very clear – they are all going down, and they have been going down for some time," she says. "So I think that there's no reason to believe that those are going to improve on their own in the next five years, in the next decade, unless we do things in a concentrated fashion to make sure that those things do improve."

The full implications of the Covid-19 pandemic for a generation of children will only be realised as they play out in the years and decades to come. But for pre-school teacher Rebekah Underwood, she's seeing signs of hope with her latest class. They jump, roll and enjoy music lessons far more than their peers a year or two ago. "It's on the upswing for sure," she says. "They are more adventurous, although the social-emotional development is a little tricky."

--

For trusted insights into better health and wellbeing rooted in science, sign up to the Health Fix newsletter, while The Essential List delivers a handpicked selection of features and insights.