The bizarre space explosions scientists can't explain

Philip Drury/ University of Sheffield

Philip Drury/ University of SheffieldAstronomers have spotted around a dozen of these weird, rare blasts. Could they be signs of a special kind of black hole?

Astronomers had never seen anything like it before – something vast, in the depths of space, went boom. Telescopes on Earth picked up the astonishingly bright and unusual explosion in 2018, watching as it played out 200 million light years away.

The blast brightened rapidly and brilliantly, far more than one would expect for a regular star explosion, a supernova, before it disappeared. Given the label AT2018cow, the weird-looking blast – which was about the same size as our solar system – soon become known by a more memorable nickname: "the Cow".

Since this dazzling event, astronomers have detected a handful of other, similar explosions across the cosmos. Described as luminous fast blue optical transients (LFBots), they all share the same characteristics.

"They are very luminous," says Anna Ho, an astronomer at Cornell University in New York, hence the L in LFBot. The blue colour is a result of the explosion's extraordinarily high temperature of around 40,000C (72,000F), which shifts light to the blue part of the spectrum. The last letters in the acronym, O and T, refer to the fact these events appear in the visible light spectrum (optical) and are short-lived (transient).

Initially, scientists thought LFBots might be failed supernovae, stars that tried to explode but instead imploded, forming a black hole at their core that subsequently consumed them from the inside-out.

However, another theory is gaining traction – that cow flares are triggered when an undiscovered class of mid-sized black holes, known as intermediate mass black holes, swallow up stars that stray too close to them. A research paper published in November last year described fresh evidence for this idea, suggesting that it might be the preferred explanation. "The general sentiment is shifting in that direction," says Daniel Perley, an astronomer at Liverpool John Moores University.

If this turns out to be correct, it could provide vital proof of the existence of this elusive type of black hole – a missing link between the smallest and largest black holes in the Universe and a vital clue to one of its biggest mysteries, dark matter.

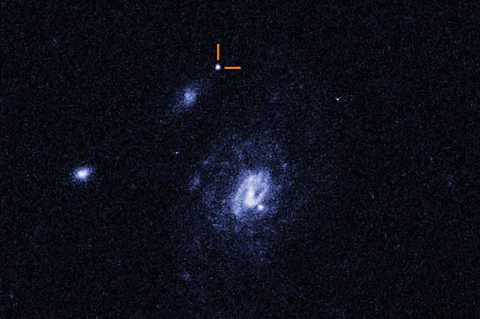

Perley et al

Perley et alThe original cow flare in 2018 was detected by a robotic survey of the sky that uses Earth-based telescopes called the Asteroid Terrestrial-impact Last Alert System (Atlas). This system caught the explosion occurring in a galaxy about 200 million light-years from Earth. Noticeably, it was up to 100 times brighter than a regular supernova, and it came and went in just a few days. Normal supernovae take weeks or even months to run their course. This explosion also had a strange, flat structure, according to a observations by researchers at the University of Sheffield in the UK.

Since then, astronomers have identified about a dozen similar events. Most have also become known by animal-themed nicknames loosely based on the letters they are randomly assigned by the astronomical survey that discovers them. ZTF18abvkwla, also witnessed in 2018, is called the Koala. ZTF20acigmel, spotted in 2020, is known as the Camel. AT2022tsd, found in 2022, is the Tasmanian devil. And 2023's AT2023fhn is called the Finch or Fawn.

Astronomers have increasingly been using telescope surveys to study large portions of the sky in an effort seek out these events. When one flares up, they can then send an alert out to other astronomers on services such as the Astronomer's Telegram, a kind of online message board for astronomical events. Such alerts aim to prompt other telescopes into action, pointing them towards the event in the hope of observing it in detail before the blast fades from view.

More like this:

• Where do Earth-threatening asteroids come from?

In November, Ho and Perley discovered another new LFBot, this time designated AT2024wpp, but has yet to gain a nickname. "We were thinking 'the Wasp'," says Ho. This explosion was particularly interesting because it was the brightest LFBot observed since the Cow, and it was also discovered very early on in its brightening phase, meaning astronomers could train lots of telescopes on it – including the Hubble space telescope – in order to learn more about it. "It's the best one since the Cow itself," says Perley.

Early observations hint that the Wasp was not caused by a failed supernova. In that theorised scenario, a star would collapse in on itself while in the process of exploding. Inside the star's shell, a black hole or a dense neutron star would then form, and blast out jets of radiation through the shell, creating what's called a central engine. This would explain the brief cow flare that was visible on Earth.

But the Wasp seemed to lack any sign of material flowing away from the explosion that scientists would expect from such an event, says Perley. However, he notes that current findings are preliminary. "We're still analysing the data," he says.

In September 2024, Zheng Cao at the Netherlands Institute for Space Research and colleagues re-examined the first detected LFBot, and also found evidence that challenged the failed supernova theory.

By studying X-ray observations of the event, they found what appeared to be a disk of material surrounding the explosion. After making a computer model of the disk, they found that it looked like the remnants of a star that was being eaten by an intermediate mass black hole, one about 100 to 100,000 times the mass of our Sun. Larger black holes could have a mass millions or even billions of times greater than our Sun. (Find out just how big black holes can get in this article about the largest black holes in the Universe.)

As the star was eaten, it would occasionally cause the black hole to suddenly brighten as larger chunks of the star were consumed, producing the Cow flares spotted by astronomers on Earth.

"I believe our study supports the intermediate mass black holes nature of AT2018cow and similar LFBots," says Cao.

Another idea is that LFBots are actually a class of giant stars called Wolf-Rayet stars that are being torn apart by much smaller black holes only 10 to 100 times the mass of our Sun. Brian Metzger, a theoretical astrophysicist at Columbia University in New York, is among those who support this idea. He says these could form in a similar way to pairs of black holes – which have been detected by the gravitational waves they produce – except on this occasion only one of the stars becomes a black hole.

Nasa

NasaThe intermediate mass black holes theory is perhaps the most alluring and favoured idea at the moment, though. If correct, it would mean that LFBots are a unique opportunity for us to study mysterious mid-sized black holes. While astronomers are reasonably confident that intermediate mass black holes exist in the Universe, no-one has yet found definitive proof for them.

And they could be extremely important, acting as the missing link between the smallest black holes in the cosmos and the largest, supermassive black holes such as the one at the centre of our own galaxy. LFBots could reveal the locations of intermediate mass black holes, and how common they are.

"The intermediate mass black hole model is the most exciting," says Perley. "It is still kind of debated in the community whether intermediate mass black holes really exist. The evidence has been quire sparing."

To find out for certain what LFBots are, we really need a much larger sample of them. "Unfortunately, they're really rare," says Perley. Data on around 100 of them would be an ideal next step, he adds. We might get a little closer to that number next year, when an Israeli orbital telescope called the Ultraviolet Transient Astronomy Satellite (Ultrasat) is set to launch. It is expected to find many more LFBots among other cosmic transients, thanks to its very large field of view of 204 square degrees, equivalent to seeing 1,000 full Moons.

Other space telescopes, such as the James Webb Space Telescope (JWST), could gather more data about singular LFBots so long as they could be trained in the direction of an explosion while it is brightening. "JWST would be perfect," says Metzger. However, getting time on the telescope to do such observations has proved difficult. "I proposed this two times," says Ho, but she had no luck. "I'll try again this year."

Until more data arrives, the mystery of these strange explosions will linger. What is clear is that LFBots have proved far more unusual than anyone expected.

"I thought this was going to be a fun, one-off project," says Perley. "But it turned out to really be this completely separate type of phenomenon. They have become more and more interesting."

--

If you liked this story, sign up for The Essential List newsletter – a handpicked selection of features, videos and can't-miss news, delivered to your inbox twice a week.