Why printers add secret tracking dots

Electronic Frontier Foundation/CC BY 3.0

Electronic Frontier Foundation/CC BY 3.0They’re almost invisible but contain a hidden code – and now their presence on a leaked document has sparked speculation about their usefulness to FBI investigators.

BBC Future has brought you in-depth and rigorous stories to help you navigate the current pandemic, but we know that’s not all you want to read. So now we’re dedicating a series to help you escape. We’ll be revisiting our most popular features from the last three years in our Lockdown Longreads.

You’ll find everything from the story about the world’s greatest space mission to the truth about whether our cats really love us, the epic hunt to bring illegal fishermen to justice and the small team which brings long-buried World War Two tanks back to life. What you won’t find is any reference to, well, you-know-what. Enjoy.

On 3 June 2017, FBI agents arrived at the house of government contractor Reality Leigh Winner in Augusta, Georgia. They had spent the last two days investigating a top secret classified document that had allegedly been leaked to the press. In order to track down Winner, agents claim they had carefully studied copies of the document provided by online news site The Intercept and noticed creases suggesting that the pages had been printed and “hand-carried out of a secured space”.

In an affidavit, the FBI alleges that Winner admitted printing the National Security Agency (NSA) report and sending it to The Intercept. Shortly after a story about the leak was published, charges against Winner were made public.

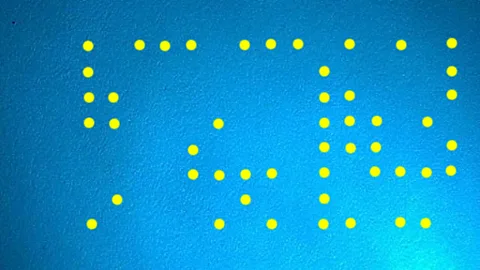

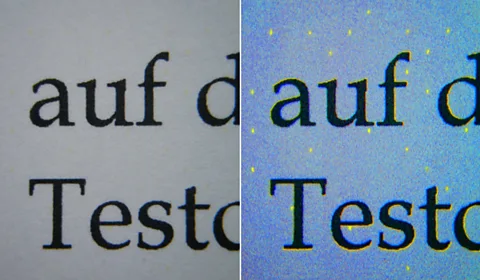

At that point, experts began taking a closer look at the document, now publicly available on the web. They discovered something else of interest: yellow dots in a roughly rectangular pattern repeated throughout the page. They were barely visible to the naked eye, but formed a coded design. After some quick analysis, they seemed to reveal the exact date and time that the pages in question were printed: 06:20 on 9 May, 2017 – at least, this is likely to be the time on the printer’s internal clock at that moment. The dots also encode a serial number for the printer.

These “microdots” are well known to security researchers and civil liberties campaigners. Many colour printers add them to documents without people ever knowing they’re there.

Florian Heise/Wikipedia

Florian Heise/WikipediaIn this case, the FBI has not said publicly that these microdots were used to help identify their suspect, and the bureau declined to comment for this article. The US Department of Justice, which published news of the charges against Winner, also declined to provide further clarification.

In a statement, The Intercept said, “Winner faces allegations that have not been proven. The same is true of the FBI’s claims about how it came to arrest Winner.”

But the presence of microdots on what is now a high-profile document (against the NSA’s wishes) has sparked great interest.

“Zooming in on the document, they were pretty obvious,” says Ted Han at cataloguing platform Document Cloud, who was one of the first to notice them. “It is interesting and notable that this stuff is out there.”

Another observer was security researcher Rob Graham, who published a blog post explaining how to identify and decode the dots. Based on their positions when plotted against a grid, they denote specific hours, minutes, dates and numbers. Several security experts who decoded the dots came up with the same print time and date.

Microdots have existed for many years. The Electronic Frontier Foundation (EFF) maintains a list of colour printers known to use them. The images below, captured by the EFF, demonstrate how to decode them:

As well as perhaps being of interest to spies, microdots have other potential uses, says Tim Bennett, a data analyst at software consultancy Vector 5 who also examined the allegedly leaked NSA document.

“People could use this to check for forgeries,” he explains. “If they get a document and someone says it’s from 2005, [the microdots might reveal] it’s from the last several months.”

If you do encounter microdots on a document at some point, the EFF has an online tool that should reveal what information the pattern encodes.

Hidden messages

Similar kinds of steganography – secret messages hidden in plain sight – have been around for much longer.

Slightly more famously, many banknotes around the world feature a peculiar five-point pattern called the Eurion constellation. In an effort to avoid counterfeiting, many photocopiers and scanners are programmed not to produce copies of the banknotes when this pattern is recognised.

- READ MORE: The secret codes on banknotes

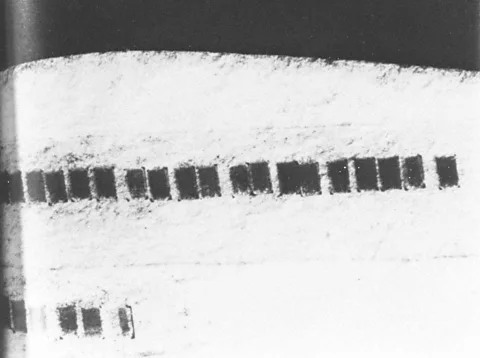

The NSA itself points to a fascinating historical example of tiny dots forming messages – from World War Two. German spies in Mexico were found to have taped tiny dots inside the envelope concealing a memo for contacts in Lisbon.

At the time, these spies were operating undercover and were trying to get materials from Germany, such as radio equipment and secret ink. The Allies intercepted these messages, however, and disrupted the mission. The tiny dots used by the Germans were often simply bits of unencrypted text miniaturised to the size of a full-stop.

This sort of communication was widely used during WWII and afterwards, notably during the Cold War. There are reports of agents operating for the Soviet Union, but based undercover in West Germany and using letter drops to transmit these messages.

Wikipedia

WikipediaAnd today, anyone can try using microtext to protect their property – some companies, such as Alpha Dot in the UK, sell little vials of permanent adhesive full of pin-head sized dots, which are covered in microscopic text containing a unique serial number. If the police recover a stolen item, the number can in theory be used to match it with its owner.

Many examples of these miniature messages do not involve a coded pattern as with the output of many colour printers, but they remain good examples of how miniscule dispatches physically applied to documents or objects can leave an identifying trail.

Some forms of text-based steganography don’t even use alphanumeric characters or symbols at all. Alan Woodward, a security expert at the University of Surrey, notes the example of ‘Snow’ – Steganographic Nature Of Whitespace – which places spaces and tabs at the end of lines in a piece of text. The particular number and order of these white spaces can be used to encode an invisible message.

“Locating trailing whitespace in text is like finding a polar bear in a snowstorm,” the Snow website explains.

Woodward points out, though, that there are usually multiple ways of tracing documents back to whoever printed or accessed them.

“Organisations such as the NSA have logs of every time something is printed, not just methods of tracking paper once printed,” he says. “They know that people know about the yellow dots and so they don’t rely upon it for traceability.”

There is a long-running debate over whether it is ethical for printers to be attaching this information to documents without users knowing. In fact, there has even been a suggestion that it is a violation of human rights and one MIT project has tracked more than 45,000 complaints to printer companies about the technology.

Still, many believe that the use of covert measures to ensure the secrecy of classified documents remains necessary in some cases.

“There are things that governments should be able to keep secret,” says Ted Han.

However, he adds, “I hope that folks think about their operational security and also about how journalists can protect themselves – and their sources as well.”

If you liked this story, sign up for the weekly bbc.com features newsletter, called “If You Only Read 6 Things This Week”. A handpicked selection of stories from BBC Future, Earth, Culture, Capital, and Travel, delivered to your inbox every Friday.

Is your printer sharing your history?

According to a freedom of information request to the US Secret Service made by journalist Theo Karantsalis in 2012, these printer manufacturers agreed to fulfil "document identification requests":