Oscars 1999: Why Harvey Weinstein was behind the most controversial best picture win ever

Alamy

AlamyWhen Shakespeare in Love won best picture in 1999 – keeping Steven Spielberg's Saving Private Ryan off top spot – it was the culmination of a campaign that changed the awards landscape forever.

When Harrison Ford walked out on stage to present the final award of the night at the 1999 Academy Awards, many in the audience thought they were about to see a replay of the moment, five years earlier, when Ford had announced Schindler's List as the best picture winner, and delightedly handed the Oscar to his friend and former collaborator, Steven Spielberg.

Everything looked set for Spielberg to pick up his second best picture award, this time for his war epic, Saving Private Ryan. The film — famous for its 24-minute opening scene of the Allied troops storming Omaha beach — had been widely hailed a masterpiece by critics. Moments earlier that evening, Spielberg had picked up the best director award, a sign that best picture was probably in the bag, too.

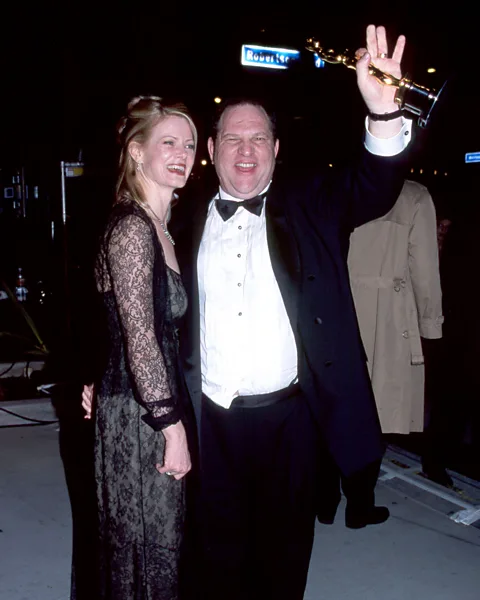

Instead, a somewhat subdued Ford opened the envelope and announced three words people weren't expecting… "Shakespeare in Love". Cameras immediately cut to the stunned faces of the film's team, including its star Gwyneth Paltrow, already a winner that night for best actress. There were shrieks, bear hugs and fist pumps. And no one looked happier than Harvey Weinstein, then head of Miramax, the studio behind Shakespeare in Love. Elsewhere in the audience, there was shock and bemusement. The win has gone down as one of the most controversial in Oscars' history — not only for the surprise result, but for the campaign that led up to it, which changed the awards landscape forever.

More like this:

- The Ukraine doc set to follow Navalny Oscar win

Watching the moment back now, it's hard to separate it from what we now know about Harvey Weinstein, and his horrific catalogue of rape and sexual assault. No doubt at the time, there were people in the auditorium aware of Weinstein's behaviour, if not the extent of it. Paltrow, who would later be a vital source in helping to expose Weinstein, was sexually harassed by him when she was 22. But in 1999, publicly at least, Weinstein's reputation was more that of a notorious bully — someone who would stop at nothing to get what he wanted. And in the nineties, that was Academy Awards.

Oscar campaigning was nothing new — studios have always made efforts to promote their films and stars in awards season, hoping to cement them in the minds of Academy Award voters. In 1930, in the run-up to only the second ever ceremony, well-connected actress Mary Pickford invited the voting committee around for tea to help bag herself a win.

Alamy

AlamyIn the 1990s, though, Weinstein took it up a level. "He turned Oscar campaigning into much more of a bloodsport," Michael Schulman, author of Oscar Wars: A History of Hollywood in Gold, Sweat and Tears, tells BBC Culture. "From his perspective, and from the perspective of the people who worked for him at Miramax, they had to campaign for Oscars because they were the underdogs. They were the indie company that put out edgy, arty films like The Crying Game and Pulp Fiction."

In Peter Biskind's 2004 book, Down and Dirty Pictures, Weinstein said: "In those days, the studios had a lock on the Oscars, because none of the indies campaigned aggressively. The only thing that we did to change the rules was, rather than just sitting it out and getting beat because somebody has more money, more power, more influence, we ran a guerrilla campaign."

Weinstein ran awards campaigns like political ones. "There's two parts of a political campaign," says Schulman. "There's the messaging and there's the ground game. And in the 90s, Weinstein did both really well." Crafting a narrative around a film or an actor was part of it. For My Left Foot, Weinstein's first big Oscars push, Daniel Day Lewis — who went on to win best actor — appeared in Washington to support the Americans with Disabilities Act, and Miramax arranged a screening of the film for House and Senate members.

For the ground part of the campaign, Miramax left no vote unturned, calling Academy members to check they'd received their VHS copy of a film, setting up special screenings — including in a retirement home for Academy members — and wheeling their talent out at lunches, panels and parties to schmooze with voters.

Alamy

AlamyIn 1997, Miramax had their first best picture winner, The English Patient — and it only made Weinstein hungry for more. After Miramax was largely shut out at the 1998 awards, they knew they had to campaign even harder the next year — especially considering who they were up against.

Saving Private Ryan was released in summer 1998 and was an immediate critical and commercial hit. By that autumn, most assumed it was the frontrunner for the best picture award. "Saving Private Ryan was Spielberg's movie about his father's generation, about 'the greatest generation', and it meant so much to him," says Schulman. "When it came out, it was immediately the frontrunner. Everyone at DreamWorks kind of assumed that they were gliding toward Oscars victory and then, at the end of the year, along comes Shakespeare in Love."

Directed by John Madden, and starring Gwyneth Paltrow, Joseph Fiennes, Colin Firth and Judi Dench, Shakespeare in Love is a fictional imagining of a young William Shakespeare falling for a woman called Viola (Paltrow) and being inspired to write Romeo & Juliet. Though it was a late entry into the awards race, the film played well with both critics and the public, and when the 1999 Oscar nominations came out, it had 13 nods to Saving Private Ryan's 11.

Getty Images

Getty Images"There were a lot of legitimate reasons why people in the Academy loved Shakespeare in Love," says Schulman. "It was light and romantic and funny and frothy and clever. It was about love, whereas Saving Private Ryan was about war. It was like a breath of fresh air." It was also that specific genre that Hollywood loves to celebrate: films about acting and show business.

Even so, Spielberg — who not only directed Saving Private Ryan but co-owned DreamWorks, the studio that produced it – didn't feel the need to go out and schmooze Academy voters. "He found campaigning gauche, especially for a movie with this important subject matter," says Schulman.

Miramax, meanwhile, was throwing everything but the kitchen sink at their campaign. "For Shakespeare in Love, we used the playbook for The English Patient — turbocharged, on steroids," said Mark Gill, then Miramax's LA President, in an oral history of the campaign published in The Hollywood Reporter in 2019. "It was just absolutely murderous the whole way through. I mean, the hours were ridiculous and the demands were insane, just unbelievably crazy stuff."

Things reached a head when word spread that Weinstein was secretly badmouthing Saving Private Ryan to journalists, trying to plant the idea that the film tailed off after the first 25 minutes. This kind of negative campaigning was a huge no-no in the Oscars race. Spielberg refused to stoop to Weinstein's level, but DreamWorks stepped up their campaign, running lots more ads in the trade press.

The battle between the two films drew attention from the press. In a lengthy New York Magazine article published the week before the ceremony, entertainment journalist Nikki Finke said the upcoming show was "one of the most contentious ceremonies in the 72-year history of the Academy". When the evening of the Oscars finally arrived, it felt less like a celebration of film and more like the climax of a months-long dogfight. Even so, few really believed Weinstein would snatch the main award of the night.

Alamy

AlamyBy the time of the final award, Shakespeare in Love had won six Oscars and Saving Private Ryan five. It looked like the night might end with a straight tie, but when Shakespeare in Love won best picture, there were gasps throughout the auditorium. "It was a shock, but it was also a confirmation of what everyone had been primed to believe, which was that the Miramax campaign was out of control," says Schulman.

Studio heads rarely appear on stage at awards shows, but Weinstein had put his name as a producer on Shakespeare in Love, meaning he was entitled to go up to receive the award. Once there, he elbowed his way to the front, denying producer Edward Zwick his moment of glory. In an extract from a forthcoming memoir published in Air Mail, Zwick recalled: "As I stand there, the rictus of a frozen grin immobilising my face, it occurs to me to shove him over the edge of the stage into the orchestra pit."

Meanwhile Spielberg made a swift exit, skipping the press room. "There's a famous photo of him at the after party with his directing Oscar, looking like someone had just killed his dog," says Schulman. Weinstein's win was the talk of the town — mostly for the wrong reasons. DreamWorks' marketing chief Terry Press vowed she would never let it happen again. "I was devastated, and Steven was no longer naive about what Harvey was capable of," she said.

Yet as controversial as Weinstein’s campaign was — and despite the bad taste it left in the industry — it marked a permanent shift in how studios approached awards season. He might have won the battle, but he’d started a war. "It was an arms race," says Schulman. "Every studio now felt that they needed to run a Miramax-style campaign. So you now had everyone in Hollywood trying to out-campaign each other and hiring a battalion of campaign strategists, and that's how we got this bloated cottage industry of awards campaigning."

Alamy

AlamyThe next year, DreamWorks went full throttle with their campaign for American Beauty and pulled off the win. They did it again in 2001 with Gladiator. Remnants of Weinstein's methods could be seen everywhere. Negative stories about films would appear during awards sessions – often with suspicions that they were planted. In 2002, various accusations, including ones of antisemitism were levelled at John Nash – the mathematician whose story was brought to the screen in Best Picture nominee A Beautiful Mind – in the run-up to the awards. Nevertheless, the film still took home the big prize.

Other campaigning methods continued to prove controversial. When Gangs of New York was nominated for best picture, an opinion piece appeared in the press endorsing the film, apparently written by Robert Wise, the director of The Sound of Music and a former Academy president. Except, it turned out it had actually been ghostwritten by someone in the publicity department at Miramax. As a result, the Academy banned "any advertising that includes quotes or comments by academy members".

Last year, there was controversy when Andrea Riseborough landed a surprise Oscar nomination for her role in To Leslie, which some attributed to a last-minute flurry of public endorsements and gushing social media posts about her performance from fellow actors, including Jennifer Aniston, Gwyneth Paltrow and Kate Winslet. Michelle Yeoh also raised eyebrows when she shared a screenshot of a Vogue story suggesting she was a more worthy winner than Cate Blanchett — violating rules that forbid references to competitors. Once again, the Academy tightened up its regulations.

But how much sway can a campaign really have? The Academy is made up of industry professionals who you would hope care enough about films not to be swayed by a few extra adverts or a handshake from an A-list actor. Was Saving Private Ryan really "robbed"? Or were more voters just charmed by a romantic comedy than a war epic that year? "A campaign cannot win an Oscar for a movie that nobody likes," says Schulman. Where it is important is making sure your movie is in the conversation — and stays there. This is especially vital at the nominations stage, where voters are choosing from potentially hundreds of movies and performances. "You have to fight for this oxygen and campaign smartly," Schulman adds.

Carefully timed press can remind voters of a film or performance's merits. For instance, though Barbie was released last summer, America Ferrera popped up for another round of press at the start of this year — a week before the nomination voting period began — much of it focusing on her famous monologue in the film. When the nominations were announced later in January, she had a best supporting actress nod.

Sometimes, the methods for getting a film attention are a little more unorthodox — such as Anatomy of a Fall flying its breakout canine star Messi around the world for appearances at events (another move out of the Weinstein playbook — Uggie the dog was a vital part of the awards campaign for Miramax's best picture winner The Artist in 2012).

Twenty-five years on from Shakespeare in Love's shock victory, Oscar campaigning continues to be a fraught — and lucrative — business. According to The Hollywood Reporter, consultants can earn $25,000 (£19,542) a month in retainer fees, plus expect bonuses of $25,000 for securing a film a nomination, and $50,000 (£39,084) for a win.

In some cases, as much or more is spent on the awards campaign than making the movie itself. According to Vulture, Netflix was estimated to have spent between $40 and $60 million on their campaign for Roma — though they failed to get the best picture win. This year, the streamer has pushed hard for Maestro — as has its star and director, Bradley Cooper. But Cooper — who few think will take home a top award — is also a cautionary tale for appearing to want an Oscar too much, which may be just as damaging as not campaigning enough.

But why, when most of us know awards shows are no guarantee of a film or filmmaker's legacy (Hitchcock famously never won an Oscar), do studios still care enough to pour millions each year into trying to win them? Michael Schulman refers to an answer he was given by Hollywood executive Terry Press for his book. "I asked her, 'if it doesn’t always pay off financially, why do people still want them?' She told me: 'Ego and bragging rights. It's a town built on a rock-solid foundation of insecurity'."

If you liked this story, sign up for The Essential List newsletter – a handpicked selection of features, videos and can't-miss news delivered to your inbox every Friday.