Russia's next move? The countries trying to Putin-proof themselves

BBC

BBC"I joined the air force 35 years ago, aged 18, and went straight to Germany, based on a Tornado aircraft," says British Air Commodore Andy Turk, who is now deputy commander of the Nato Airborne Early Warning & Control Force (AWACS). "It was towards the end of the Cold War and we had a nuclear role back then.

"After the War, we hoped for a peace dividend, to move on geopolitically, but clearly that's not something Russia wants to do. And now my eldest son is banging on the door to join the air force, wanting to make a difference too... It does feel a little circular."

We are around 30,000 feet above the Baltic Sea, on a Nato surveillance plane equipped with a giant, shiny, mushroom-resembling radar, enabling crew members to scan the region for hundreds of miles around, looking for suspicious Russian activity.

Air policing missions like this - and Nato membership more broadly - have long made tiny Baltic nations of Lithuania, Latvia and Estonia (which neighbour Russia) feel safe. But US President Donald Trump is changing that, thanks to his affinity with Vladimir Putin, which has been evident since his first term in office.

Trump has been very clear with Europe that, for the first time since World War Two, the continent can no longer take US military support for granted.

That leaves the Baltics nervously biting their nails. They spent 40 years swallowed up by the Soviet Union until it broke apart at the end of the Cold War.

They are now members of both the EU and Nato, but Putin still openly believes the Baltics belong back in Russia's sphere of influence.

And if the Russian president is victorious in Ukraine, might he then turn his attention towards them - particularly if he senses that Trump might not feel moved to intervene on their behalf?

'Russia's economy is being retooled'

Ian Bond, deputy director of the Centre for European Reform, thinks that if a long-term ceasefire is eventually agreed in Ukraine, Putin would be unlikely to stop there.

"Nobody in their right mind wants to think that a European war is around the corner again. But the reality is an increasing number of European intelligence officials have been telling us that…

"Whether this is coming in three years or five years or ten years, what they are saying is the idea that peace in Europe is going to last forever is now a thing of the past."

Getty Images

Getty ImagesRussia's economy is currently on a war footing. Roughly 40% of its federal budget is being spent on defence and internal security.

More and more of the economy is being devoted to producing materials for war.

"We can see what the Russian economy is being retooled to do," observes Mr Bond, "and it ain't peace."

'Tricks and tactics' at the Estonia border

When you travel to windswept Narva, in northern Estonia, you see why the country feels so exposed.

Russia borders Estonia, all the way from north to south. Narva is separated from Russia by a river with the same name. A medieval looking fortress straddles each bank – one flying the Russian flag and the other, the Estonian. In between is a bridge – one of Europe's last pedestrian crossings still open to Russia.

"We are used to their tricks and their tactics," Estonian Border Police Chief Egert Belitsev told me.

"The Russian threat is nothing new for us." Right now, he says, "there are constant provocations and tensions" on the border.

The border police have recorded thermal imaging of buoys in the Narva River that demarcate the border between the two countries being removed by Russian guards under the cover of darkness.

"We use aerial devices – drones, helicopters, and aircraft, all of which use a GPS signal – and there is constant GPS jamming going on. So Russia is having huge consequences on how we are able to carry out our tasks."

Later on, keeping to the Estonian side, I walked along the snow-covered bridge crossing towards the Russian side and watched the Russian border guard watching me, watching him. We were just metres away from each other.

Last year, Estonia furnished the bridge with dragon's teeth – pyramidal anti-tank obstacles of reinforced concrete.

I've not heard anyone suggest Russia would send tonnes of tanks over. It doesn't need to. Even a few troops could cause great instability.

Some 96% of people in Narva are mother-tongue Russian speakers. Many have dual citizenship.

Estonia worries a confident Vladimir Putin might use the big ethnic Russian community in and around Narva as an excuse to invade. It's a playbook he's used before in Georgia as well as Ukraine.

In a dramatic indication of the growing anxiety, Estonia, alongside Lithuania and Poland, jointly announced this week that they're asking their respective parliaments to approve a withdrawal from the international anti-personnel mines' treaty which prohibits the use of those mines, signed by 160 countries worldwide.

This was to allow them "greater flexibility" in defending their borders, they said. Lithuania had already withdrawn from an international convention banning cluster bombs earlier this month.

Are non-Nato nations at greater risk?

Camille Grand, former Assistant Secretary General for Defence Investment at Nato, thinks that post-Ukraine, Putin would be more likely to target a non-Nato country (such as Moldova) rather than provoke a Nato nation – because of the lower risk of international backlash.

Estonia and the other Baltic nations were traditionally more vulnerable than the rest of Nato, as they were geographically isolated from the alliance's members in western Europe, according to Mr Grand. But that has been largely resolved now, since Sweden and Finland joined Nato, following Russia's full-scale invasion of Ukraine.

"The Baltic Sea has become the Nato Sea," he notes.

Dr Marion Messmer, a senior research fellow on the International Security Programme at Chatham House, thinks the most likely trigger for a war with Russia would be miscalculation, rather than design.

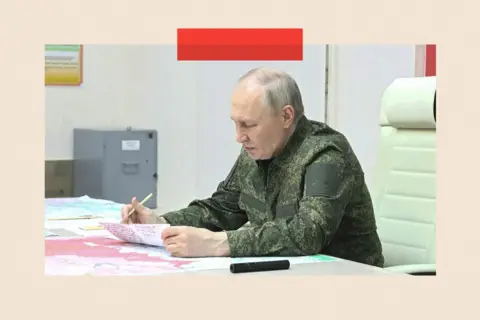

Kremlin Press Office handout via Getty Images

Kremlin Press Office handout via Getty ImagesIf peace is agreed in Ukraine, Dr Messmer predicts that Russia will probably continue with misinformation campaigns and cyber warfare in Europe, as well as sabotage and espionage in the Baltic Sea. "I think they are likely to continue with any kind of destabilising activity, even if we are to see a peace that's positive for Ukraine."

Dr Messmer continues: "One of the risks I see is that essentially an accident could happen in the Baltic Sea that's completely inadvertent, but that's essentially a result of either Russian grey zone activity or Russian brinkmanship where they thought they had control of a situation and it turns out they didn't. That then turns into a confrontation between a Nato member state and Russia that could spiral into something else."

But Mr Grand was keen not to totally downplay the risk of Putin targeting the Baltics.

How together is Nato?

Presumably, the Russian president would first mull how likely Nato allies would be to retaliate.

Would the US, or even France, Italy or the UK, risk going to war with nuclear power Russia over Narva, a small part of tiny Estonia, on the eastern fringe of Nato?

And suppose we were to see a repeat of what happened in the Donbas in eastern Ukraine in 2014 when Russian paramilitaries engaged in fighting did not identify as Russian soldiers? This allows Putin plausible deniability - and in those circumstances, would Nato wade-in to help Estonia?

If they didn't, the advantages for Putin might be tempting. The unity principle of the western military alliance he loathes would be undermined.

He'd also destabilise the wider Baltics, probably socially, politically, and economically, as a Russian incursion – however limited – would likely put off foreign investors viewing this as a stable region.

Another concern that has been discussed in Estonia is that Donald Trump could end up pulling out, or significantly reducing, the number of troops and military capabilities the US has long stationed in Europe.

Estonian Defence Minister Hanno Pevkur put a brave face on things when I met him in the capital Tallinn: "Regarding (US) presence, we don't know what the decision of the American administration is.

"They have said very clearly they will focus more on the Pacific and they've said clearly Europe has to take more responsibility for Europe. We agree on that.

"We have to believe in ourselves and to trust our allies, also Americans… I'm quite confident that attacking just even a piece of Estonia, this is the attack against (all of) Nato."

"And this is the question then to all the allies, to all 32 members," Pevkur adds. "Are we together or not?"

Putin-proofing

This new and nagging sense of insecurity, or at least unpredictability, in the Baltics and Poland – what Nato calls its "eastern flank", close to Russia – is evident in the kind of legislation being debated and introduced around the region.

Poland recently announced that every adult man in the country must be battle ready, with a new military training scheme in place by the end of the year. Prime Minister Donald Tusk has also expressed interest in a French suggestion that it share its nuclear umbrella with European allies, in case the US withdraws its nuclear shield.

Getty Images

Getty ImagesVoters living in the Baltics don't need persuading to devote a large proportion of public money to defence. Estonia, for example, is introducing a new law that makes it mandatory for all new office and apartment blocks of a certain size to include bunkers or bomb shelters. .

Tallinn also just announced it will spend 5% of GDP on defence from next year. Lithuania aims for 5-6%, it says.

Poland will soon spend 4.7% of GDP on defence – it hopes to build the largest army in Europe, eclipsing the UK and France. (To put that in perspective, the US spends roughly 3.7% of GDP on defence. The UK spends 2.3% and aims to raise that to 2.6% by 2027.)

These decisions in countries close to Russia may well be linked to a hope they have not yet relinquished, of keeping Trump and his security assurances onside. He repeated this month his previously stated position: "If [Nato countries] don't pay, I'm not going to defend them. No, I'm not going to defend them."

As for how much annual spending would be considered "enough" for the Trump administration, Matthew Whitaker, Trump Nominee for U.S. Ambassador to NATO, declared "a minimum defence spending level of 5%, thereby ensuring NATO is the most successful military alliance in history."

Estonia's plan B

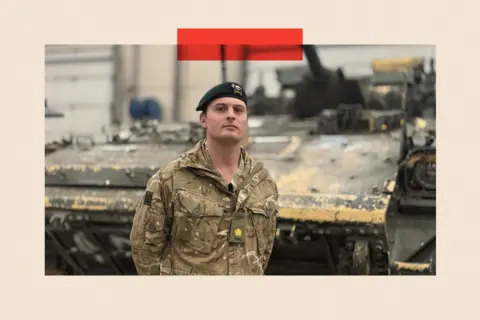

With mixed messages from Washington, Estonia is looking increasingly to European allies for reliable support. The UK plays a big role here. With 900 personnel based in Estonia, it's currently Britain's largest permanent overseas deployment. And the UK has pledged to boost its presence.

At their base in Tapa, we found immense, echoey hangars rammed with armoured vehicles.

"You'll see the Challenger Main Battle Tanks as we head down to the other end of the hangar," explains Major Alex Humphries, one of the squadron leaders in Estonia on a six-month rotation. "[They are] a really critical part of the capability. This is a really great opportunity for British forces."

Asked if Estonia had approached the UK to ask for a bigger presence, as it was feeling more vulnerable, he told me: "I think Nato at large feels exposed. This is a really important flank for our collective defence, the east. Everybody in the Baltics and in Eastern Europe feels the quite prominent and clear threat that is coming from the Russian Federation.

"We don't want this to come to war, but if it does come to war, we're fully integrated; fully prepared to deliver lethal effect against the Russian Federation to protect Estonia."

Ultimately, though, unless they come under direct attack, the precise conditions under which UK bilateral forces or Nato troops will take military action comes down to political decisions made in that moment.

So Estonia is taking nothing for granted. That's why it is busy stress testing new army bunkers on its border with Russia and investing in drone technology. Though its armed forces wouldn't be powerful enough to repel an attack by Russia alone, Estonia is studying lessons learned from invaded Ukraine – whose fate Estonia really hopes it won't have to share.

Top picture credits: Shutterstock and Getty Images

BBC InDepth is the home on the website and app for the best analysis, with fresh perspectives that challenge assumptions and deep reporting on the biggest issues of the day. And we showcase thought-provoking content from across BBC Sounds and iPlayer too. You can send us your feedback on the InDepth section by clicking on the button below.