How a scientist hopes her art will help save birds

As a scientist, Sara Cox realises the dangers her beloved birds face. As an artist, she wants to help everyone else understand too.

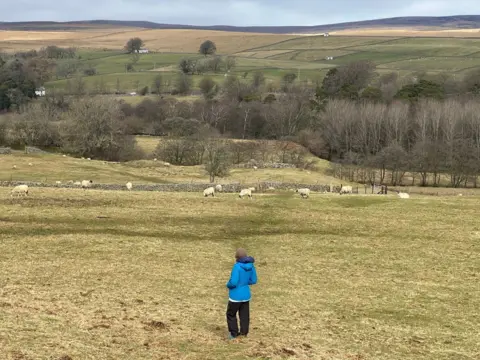

Sara stops walking and points excitedly over the drystone wall into the field beyond.

There, strutting among the scattered sheep, is a lapwing, the literal icon of the North Pennines having been immortalised in the area's logo.

"They are brilliant," Sara says, a smile across her face as she watches the small bird peck between long blades of grass.

The 58-year-old lifts one hand up behind her head and waggles her gloved fingers over the top of her homemade woolly hat.

"They have these feathers protruding from their head, they always remind me of the Egyptian queen Nefertiti and her crown."

It is a few days into spring and the lapwings have returned to Teesdale, the Durham dale Sara, her husband and two children have called home for more than 20 years.

Although the sun is out, it is a bitingly cold day in the fields above Low Force, one of the waterfalls that bejewels the River Tees.

Further down the track, Sara finds a speckled brown feather, pocketing it for closer inspection back at the wooden desk in her 275-year-old stone-floored cottage.

Sara is out for one of her regular walks for inspiration, making sketches and mental notes to help her with her work.

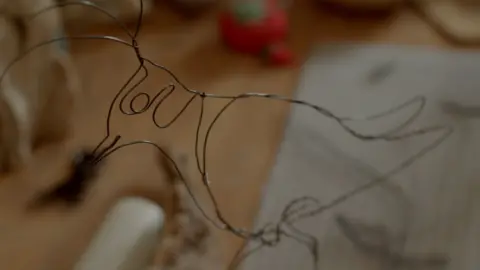

Her speciality is wire birds, intricate life-size sculptures weaved from spools of metal strands that attempt to capture the vitality of the creatures Sara loves so much.

She has made kingfishers and ravens, wrens and curlews, with some of her sculptures installed on a nature trail around Durham Wildlife Trust's reserve at Low Barns near Bishop Auckland.

Getty Images

Getty Images"It's about drawing attention to certain birds," she says, adding: "A lot of the birds I've made have been endangered or are on the red list. They're really cool little things.

"I'm very conscious the birds that come up here are diminishing in number. The environmental impact of what we do on birds is pretty horrendous, so anything I can do that makes people feel emotion or interest when they look at a sculpture is good for the environment."

Sara is as adept at explaining the anatomy of the birds and geology of the local rocks as she is at just marvelling at the beauty of the area and its wildlife.

She has science degrees from Aberystwyth, Sheffield and Durham, including one in zoology for which she studied sparrows for her dissertation. She is also a qualified teacher.

But she also has a lifelong love of art and passion for creating things, engendered by her grandparents and reinforced by her engineer father and a mother who, among other things, is an accomplished potter.

"They were all good with their hands," Sara says. "I grew up seeing my parents make stuff, seeing people create.

"Everybody can make, everybody is creative."

Back at her cottage in Mickleton, Sara fiddles with a strip of wire as she talks, twisting and reforming it as she eulogises over its malleability.

"If it's not the right shape, you can bend it back again," she says. "It's about using your imagination and problem solving."

It is why science and art make perfect bedfellows, she says.

At school in Sutton Coldfield, Sara was encouraged to follow scientific pursuits rather than artistic ones, a distinct separation made between the two disciplines.

"I think that's a mistake," she says, adding her later forays into artistic pursuits such as felt-making and now wire modelling are some of the ongoing "tiny rebellions" against her earlier enforced segregation.

Scientists and artists both notice things, but while scientists measure, artists interpret, Sara says.

She relies on science to produce her art, be it physics to make structures, anatomy to understand the birds or just general "problem solving".

"I'm bringing science into my sculptures all the time. It's quite a privilege to be able to take something, study it and then try and make it out nothing.

"You could build a raven from a million different materials so artists are playing to see what they can use, which is what material scientists do too.

"So scientists need artist and artists need science and the two shouldn't be separated."

There are no blueprints, each of her sculptures is based on meticulous research and a lot of trial and error.

She starts with the feet and works her way up, taking about six weeks to complete a model.

Sara has made two ravens, which she has named Huginn and Muninn after the Norse god Odin's own corvid companions.

Huginn recently spent a few weeks in London as part of the Royal Society of British Artists annual exhibition.

"It was an absolute treat to go down and they displayed him beautifully," Sara says.

"He was just checking everybody out and looking at all the people going past. I think he will have some stories to tell.

"People said to me can you bear to let him go and I was thinking 'yeah, absolutely', because that's the point of making these things.

"I want people to think about birds so it's no good if they're sitting here with me.

"I want other people to be thinking about all these amazing birds that we've got in this country, so I've just got to keep on making. There's so many to do."