'It's important to remember ordinary fighting men'

Laurence Neal

Laurence NealEighty years ago, planes and gliders packed with troops took to the skies to take part in "the battle that ended" World War Two in Europe.

This was Operation Varsity when more than 16,000 British, Canadian and American troops, who took off from 11 Essex and two Suffolk airfields at 07:00 GMT on 24 March 1945, dropped directly on top of strongly defended German lines at the River Rhine.

It was the largest single airborne operation in history and achieved its objectives in just hours, but at huge loss of life. Within weeks Victory in Europe was declared.

The story has been resonating with relatives of the men who served in Varsity. They have been getting in touch with the BBC to share their stories.

'How young they were'

Barbara Forey

Barbara Forey"The whole glider pilot thing is little-known and people don't appreciate this was the method of taking freight to battle before helicopters, so it's good to have it more widely known," said Barbara Forey.

The 72-year-old described her father Bert Bowman as "a very quiet, considered person - people often described him as a true gentlemen".

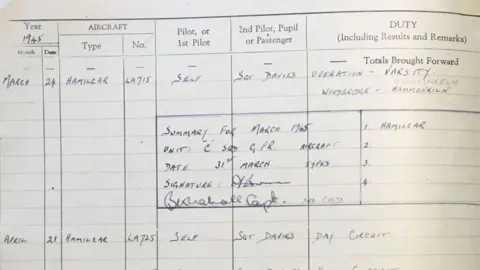

That calmness held him in good stead when, with co-pilot Peter Davies, he took part in Varsity.

"To my horror, I found the whole of my landing area covered in smoke and I just could not distinguish a thing," he wrote years later.

The staff sergeant received a Distinguished Flying Medal (DFM) for his "coolness and his skill in the face of a grave emergency" when he manged to land his huge Hamilcar cargo glider, which had been badly damaged by defending German forces.

Barbara Forey

Barbara ForeyMr Bowman had been brought up in Tottenham and Edmonton, in north London, before he was called up, aged 20, in 1940.

Two years later, he was accepted into the Glider Pilot Regiment and began intensive training as a pilot, as well as taking courses in artillery, infantry and how to survive behind enemy lines.

He was one of the first glider pilots to land during the disastrous Battle of Arnhem, which resulted in 90% casualties to the regiment, and one of the first to leave in an evacuation eight days later.

Barbara Forey

Barbara ForeyMrs Forey, 72, from Dartmouth, Devon said her father was demobbed in 1946 and was offered his old job back in insurance.

She told the BBC her father rarely talked about his wartime experiences during her childhood.

While she knew he was involved in Operation Varsity, she learned a great deal more about his experiences from notes for a talk he gave years after - as well as the information he gave her son for a school project about World War Two.

"It gives me a catch in my throat when I read about these things and you think how young they were and what they went through," she said.

'We never knew'

Laurence Neal

Laurence NealLaurence Neal's uncle was one of at least 1,070 British, Canadian and American men who died at Varsity.

"We never really knew what happened to Eddie until we saw an eyewitness source of his glider blowing up," he said.

All 31 men on board were killed and today they rest in the Reichswald Forest War Cemetery.

"He was in a lead glider and they didn't have a chance," said Mr Neal, 79, who suspects the German defenders scored a direct hit on the troop's ammunition cart.

"His platoon, B Company, had six officers and 100 other ranks before Varsity and afterwards there were two officers and 45 other ranks - more than 50% losses."

Laurence Neal

Laurence NealAlfred Edward Thomas "Eddie" Annetts, who served in the 2nd Battalion Oxfordshire and Buckinghamshire Light Infantry (Airborne), was just 22 years old.

However, "the country boy from Wiltshire" was already a veteran of the D-Day landings and among 55,000 British and Canadian troops who contributed to the primarily American-fought Battle of the Bulge, said Mr Neal, from Totton in Hampshire.

"My mother always said one of our uncles went missing and was killed, but nobody had any detail until my brother Tony started looking into it about 20 years ago," he said.

"One story he found out was there was a bit of confusion when loading the gliders at RAF Gosfield in Essex, and some blokes got onto the wrong glider, which saved their lives."

Laurence Neal

Laurence NealAfter Mr Neal's brother died, he used that research and his own to tell their uncle's story in a book By Glider to Normandy and Beyond, saying "these are the men who died for their country".

"Everyone writes biographies of generals, but ordinary fighting man are forgotten a lot of time - it's important they are remembered," he said.

'Plenty of vodka'

John Lloyd

John Lloyd"My dad's Varsity story starts with a glider crossing the Rhine as part of the 6th Airborne and then he teams up with Maj Gen Eric Bols and is among the first British troops to meet the Russian army," said John Lloyd, from Wrexham, Clwyd.

Jack Lloyd was a career soldier in his early 30s by this stage, having "joined the Army in 1933 to get away from his five sisters", according to his son.

He expected to join his local regiment - the Royal Welsh Fusiliers - but instead was sent to join the The Cameronians (Scottish Rifles) in Hamilton, South Lanarkshire.

John Lloyd

John LloydMr Lloyd said: "The first active wartime service he saw was D-Day and he progressed through France, receiving five minor wounds, until he received a nasty knock with shrapnel and was sent to recover in Brussels.

"A [Belgian] vicar sent a letter to my mother Jenny saying he was on holiday, when in fact he was sick, and then he had a few months at home with her to recover."

John Lloyd

John LloydThe rifleman was part of the 6th Airborne during Varsity and after "a hell of a fight", he appears to have become Gen Bols' batman, a uniformed orderly "who kept him clean, tidy and fed", said Mr Lloyd, as they made a rapid 600 mile (965km) dash across Germany.

"He didn't tell me the gory details of his war service, but once he told me they came within 10 miles down wind of a concentration camp and the smell was terrible, it made him ill," said Mr Lloyd.

John Lloyd

John LloydBut they did not stop because Gen Bols was under orders from Field Marshal Montgomery, the commander behind Rhine crossing operations, to get to Wismar, "to prevent the Russians from encroaching on Belgium".

Mr Lloyd said: "The British couldn't speak Russian and the Russians couldn't speak English, but there was a lots of vodka so they didn't need to speak - they just got stuck into having a party."

John Lloyd

John LloydEventually his father was demobbed and Gen Bols helped him find his first post-war job as a gardener in Andover, Hampshire.

"He only ever told me the slightly amusing stories - such as when he got lost driving a general in Scotland in 1940, or how he had his bagpipes nicked in Gibraltar - so I was shocked when I told him I was thinking of joining up and he said, 'Don't do it -war is horrible, you must avoid it at all costs," said Mr Lloyd.

Follow Essex news on BBC Sounds, Facebook, Instagram and X.