If books could kill: The poison legacy lurking in libraries

BBC

BBCThe Victorians loved the colour green. In particular, they loved a vibrant shade of emerald created by combining copper and arsenic, which was used in everything from wallpaper to children's toys.

"This colour was very popular for most of the 19th Century because of its vibrancy and its resistance to light fading," says Erica Kotze, a preservative conservator at the University of St Andrews.

"We know that many household items were coloured with arsenic-based green pigments. It was even used in confectionery."

The trouble is, the combination of elements used is toxic and that's still a problem more than a century later. And it's a particular problem when it comes to old books.

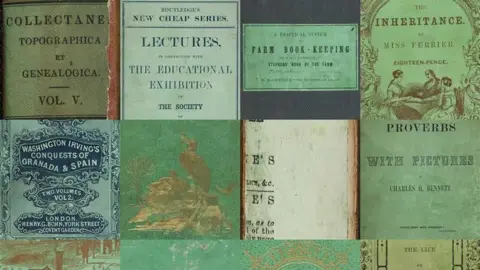

Victorian bookbinders used arsenic as well as mercury and chrome to create striking covers. And unlike domestic items, books have survived in archives around the world, creating a 21st Century problem from 19th Century fashion.

Prolonged exposure to multiple green books can cause low level arsenic poisoning.

Long-term exposure can cause changes to the skin, harm to the liver and kidneys and a reduction in red and white blood cells, which can lead to anaemia and an increased risk of infections.

In 2019, an attempt to tackle the problem was set up in Delaware between the Winterthur Museum and the state university.

The Poison Book Project tested books and drew up a list of titles which are potentially harmful to humans. These included four books in the National Library of France, which were immediately withdrawn.

Inspired by this, Erica Kotze called on her colleague Dr Pilar Gil, who trained as a biochemist before working in Special Collections at the University of St Andrews.

Dr Gil took a practical approach to surveying the thousands of historic books in their collection.

"The most important thing was to find a non-destructive, portable instrument that could tell us if it was a poisonous book or not," she says.

She rule out X-ray technology because of the fragile nature of the books being examined and instead looked to the geology department.

They had a spectrometer - a device that measures the distribution of different wavelengths of light - for detecting minerals in rocks.

"Minerals and pigments are very similar," says Dr Gil, "so I borrowed the instrument and started looking for emerald green in books."

She tested hundreds of books and then realised she was looking at a breakthrough.

"I realised there was a distinctive pattern to the toxic ones. It was a 'eureka' moment. I realised it was something that no one had seen before."

The next task was to speak to the physics department to build their own prototype.

Dr Graham Bruce, senior research laboratory manager explains how it works.

"It shines light on the book and measures the amount of light which shines back," he says.

"It uses green light, which can be seen, and infrared, which can't be seen with our own eyes. The green light flashes when there are no fragments of arsenic present, the red light when there are pigments."

The new testing device is smaller and will be less costly to produce and use than a full-scale spectrometer

It has already been used to survey the thousands of books in the St Andrews collections and in the National Library of Scotland, and the team hope to share their design with other institutions around the world.

University of St Andrews

University of St Andrews"We're lucky as a large institution to have expensive kit, so that we can test 19th Century potentially toxic books," says Dr Jessica Burge, deputy director of library and museums at the University of St Andrews.

"But other institutions with big collections may not have those resources, so we wanted to create something which was affordable and easy. It doesn't require a specialist conservator or analysis, and it's instant."

It's also a problem which isn't going away. If anything, toxic books will become more harmful as they get older and disintegrate.

Identifying them means they can stored in a safe way and still enjoyed with controlled access and precautions such as wearing gloves.

"It will continue to be a live issue," says Dr Burge.

"But I think that the biggest issue for institutions at the moment is that any book that's got a green cover from the 19th Century is being restricted because they don't know.

"And as libraries and museums, that's not really what we're about. We want people to be able to use the books and help bring back access to collections, rather than restricting their use."