'It will be a great hoax in the history of mankind': How fake Hitler diaries fooled the British press

Getty Images

Getty ImagesIn April 1983, a German magazine, Stern, and a British newspaper, The Sunday Times, claimed to have made one of the century's most extraordinary historical discoveries. In fact, it was one of the century's most extraordinary hoaxes – and the scandal that followed cost millions and ruined reputations.

On 25 April 1983, 42 years ago this week, respected German magazine Stern published what they believed to be the most spectacular historical scoop: the previously unknown private diaries of Adolf Hitler. To show off their extraordinary exclusive to the world's press, the weekly news magazine had arranged a Hamburg press conference for the same day. The story would indeed dominate global headlines – but not in the way the magazine hoped.

Three days earlier, Stern's London editor Peter Wickman had told BBC News that they were "absolutely convinced" that they had the authentic Hitler diaries in their hands. "We were very dubious at the beginning, but we had a graphologist looking at them, we had an expert who compared the paper. We had historians like Professor Trevor-Roper, and they are all convinced they are genuine."

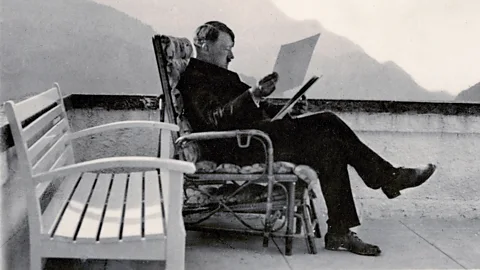

The handwritten journals ran from 1932 to 1945, covering the entire period of Hitler's Third Reich. "There are 60 diaries, they look a bit like school exercise books but with a hard cover. They have seals outside with a swastika and an eagle and inside, of course, Hitler's very spidery gothic handwriting," Wickman told the BBC.

Stern believed that their discovery had the potential to rewrite what was previously known about the Nazi leader. And the diaries' content was certainly eye-opening, revealing a little-known sensitive side to the Führer. They detailed everything from Hitler's battles with flatulence and halitosis, and the pressure from his girlfriend Eva Braun to get Olympics tickets, to notes about sending Stalin – "the old fox" – a birthday telegram. The notebooks also seemed to indicate, somewhat startlingly, that the Nazi leader was unaware of the Holocaust that was being carried out in his name.

The journals had supposedly been unearthed by Stern journalist Gerd Heidemann. The reporter was already regarded around Stern as something of a Nazi memorabilia obsessive. In 1973, the magazine had assigned him to write a story about a dilapidated yacht which had once belonged to Hitler's second-in-command, Hermann Göring. Heidemann spent a fortune buying the yacht and restoring it. He also began an affair with Göring's daughter Edda, who introduced him to a number of former Nazis. It was through these contacts, Heidemann said, that he had come across Hitler's diaries.

Alamy

AlamyHeidemann claimed that the plane had been carrying the diaries, which were salvaged from the crash and stowed away in a hayloft. In the intervening years, they had found their way to an East German collector who was now offering to sell them. The reporter would negotiate the deal to buy them, acting as intermediary between his East German source and Stern.

The promise of a sensational world exclusive, providing previously unknown insight into the mind of the Nazi dictator, proved irresistible to the magazine. But Stern was determined to keep a tight grip on who knew about their scoop, so when they hired handwriting experts to authenticate the diaries – providing them with "genuine" Hitler documents for comparison – they would only give them a few selected pages of the notebooks to look at. Stern ultimately forked out some 9.3 million Deutschmarks (£2.3m) for the volumes, and, having paid such an exorbitant sum, opted to store them in a Swiss vault for safekeeping.

The first historian to examine the diaries was Prof Hugh Trevor-Roper, also known as Lord Dacre of Glanton. In 1947, he had written a book, The Last Days of Hitler, which had brought him a great deal of academic prestige, and he was regarded as a leading expert on the Nazi dictator. He was also an independent director of The Times newspaper, which two years earlier had been acquired along with its sister paper, The Sunday Times, by Rupert Murdoch.

Lord Dacre was initially sceptical about the diaries, but flew to Switzerland to view them. His opinion began to be swayed when he heard the diaries' origin story and was told, erroneously, that chemical tests had found them to be pre-war. But what really tipped the balance for the historian was seeing the huge volume of material involved.

"The thing that struck Hugh Trevor-Roper most forcefully and certainly struck me as a non-expert when I saw the original material was the sheer scale of it," The Times editor Charles Douglas-Home told the BBC on 22 April 1983. "The enormous range of this archive. It's not just that there are nearly 60 volumes of notebooks filled out in Hitler's longhand which is there, there are about 300 of his drawings and pictures and personal documents such as his party card. I remember there are the drawings which he submitted to art school when he was a young man hoping to get into art school, and there is a painting, an oil painting and so on. Now a forger would have to be very good to forge across that whole range."

In History

In History is a series which uses the BBC's unique audio and video archive to explore historical events that still resonate today. Subscribe to the accompanying weekly newsletter.

Lord Dacre became convinced that the journals were genuine, even writing an article for The Times vouching for their authenticity and declaring that historic events might need to be re-evaluated in light of them. As word got out about the Hitler diaries, a bidding war developed over their serialisation rights, with The Sunday Times proprietor, Murdoch, flying over to Zurich to negotiate a deal in person.

With serialisation deals signed, Stern hastily planned a press conference to announce the publication of Hitler's diaries to the world. But even before the notebooks' grand reveal, doubts were being raised about their veracity – not least by the staff of The Sunday Times themselves, who had been burnt before. In 1968, the newspaper had made a down payment on diaries supposedly written by the Italian fascist leader Benito Mussolini, which had also been vouched for, by his son no less. "But they turned out to be fakes devised by two little old ladies who lived in Vercelli outside Milan," journalist Phillip Knightley, who worked for The Sunday Times's investigative team, told Witness History in 2011.

The hoax is exposed

However, Murdoch was certain about the diaries and, despite the reservations of its editor, Frank Giles, rushed the serialisation into print in The Sunday Times with the headline "world exclusive" the day before Stern's press announcement.

Giles rang Lord Dacre seeking reassurance about the story only to have the historian confess that he was not so much having doubts as making "a 180-degree turn" regarding the diaries' authenticity. "Everybody in the room, all the newspaper executives slumped down in their chairs and put their heads in their hands because we had lost our principal authenticator," said Knightley. "It was clear that the story was absolutely wrong."

The Sunday Times could still have stopped the presses and changed the front page. But when Giles rang the proprietor, "Murdoch said, 'Just because Dacre has been vacillating for all this time, screw him, we'll publish,'" recalls Knightley.

For Stern, things would just get worse at its news conference the next day. After editor-in-chief Peter Koch declared that he was "100% convinced that Hitler wrote every single word in those books", Lord Dacre, the very historian who had vouched they were the real deal, admitted under questioning that he was having second thoughts.

To the horrified looks of the Stern executives, Lord Dacre said that he wasn't able to establish a link between the plane crash and the alleged diaries and that he had been rushed into making a judgement. "I must say as a historian, I regret that the normal methods of historical verification have, perhaps necessarily, been to some extent sacrificed to the requirements of the journalistic scoop," he said.

The day after the chaotic press conference, Charles Hamilton, a US autographs dealer, told BBC Breakfast that as soon he saw the diaries' pages he "could smell the ebullient odour of forgeries". Hamilton said that he knew the signature wasn't authentic because he was constantly offered fake Hitler documents. "Shortly it will be established without any question, and without any panel of experts which I think is superfluous at the present time, the whole affair will die down and it will be a great hoax in the history of mankind," he said.

Alamy

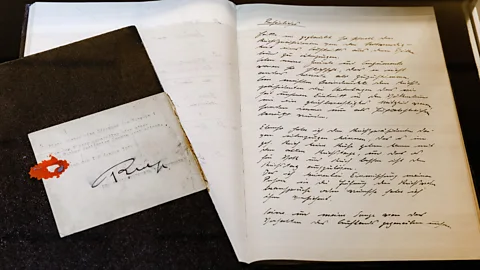

AlamyAnd he was not wrong. Within two weeks, rigorous forensic analysis had exposed the diaries as fakes. Not only, as Hamilton had pointed out to the BBC, was Hitler's supposed signature not accurate, but chemical testing revealed that their paper, glue and ink were not manufactured until after World War Two. The diaries were peppered with errors, modern-day phrases and historical inaccuracies, sometimes referring to information that Hitler could not have possibly known.

In the wake of these revelations The Sunday Times quickly abandoned its serialisation and printed an apology. Stern also publicly apologised for having fallen for the hoax.

Reputations fall, circulations rise

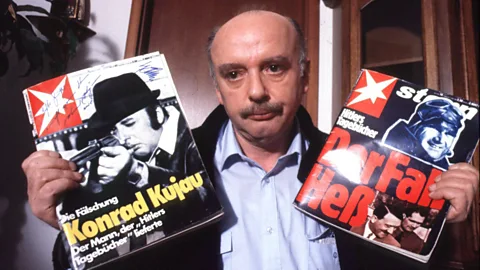

Under pressure, Heidemann revealed that the East German source supplying the diaries was Konrad Kujau – a counterfeiter who turned out to be the author of the works. Kujau was a skilled artist, but his forgeries were far from sophisticated. Seeking inspiration, he had plagiarised large parts of Max Domarus's book Hitler: Speeches and Proclamations 1932-1945, and as a result had copied word for word some of the chronological and factual mistakes in that book's first edition. To try to give the journals a more personal feel, he had imagined a more prosaic side to the Führer's life, throwing in entries like "I can't even get off work and visit Eva", "Have to go to the post office, to send a few telegrams", and "Eva says I have bad breath". Kujau had even struggled with the elaborate Gothic initials he used on the diary covers, accidentally sticking the initials FH to them instead of AH. He had then attempted to age the notebooks by merely pouring tea over them and bashing them on his desk.

What helped with the initial authentication of the diaries was that Kujau was such a prolific forger of Nazi memorabilia that many of the "genuine" documents Stern had given to experts, to enable them to compare Hitler's handwriting, had actually also been produced by Kujau himself. He was arrested by the police and admitted to his role in the hoax. He even went so far as to demonstrate his guilt by writing his confession in the style of Hitler's handwriting. In 1985, he was found guilty of fraud and forgery and sentenced to four-and-a-half years in prison.

On further investigation, the police found Heidemann had also inflated the prices he said his source was requesting for the diaries, and had been skimming money off the top of the sums paid by Stern. He seems to have done this to fund his lavish lifestyle, the upkeep of his Nazi yacht and his penchant for buying ever more dictators' memorabilia (he would later claim to possess Idi Amin's underwear). He, like Kujau, was convicted in 1985 of fraud and was sentenced to four years, eight months. At his trial, Heidemann maintained that he too had been duped, but Kujau always insisted that the reporter knew the diaries were fakes.

In the fallout from the scandal, Lord Dacre's reputation as a historian would be permanently tarnished. Koch and another of Stern's editors would lose their jobs, while Giles would be removed from his role as The Sunday Times editor. Even Murdoch would later claim to the Leveson Inquiry into media ethics in 2012 that his decision to run with the story "was a major mistake I made, I take full responsibility for it. I will have to live with it for the rest of my life."

However, his newspaper's circulation was boosted by his decision to print the false story. And since Murdoch had insisted on a clause that Stern return all the money paid to it by The Sunday Times if the diaries were shown to be fake, the media mogul would only profit financially from the hoax.

--

For more stories and never-before-published radio scripts to your inbox, sign up to the In History newsletter, while The Essential List delivers a handpicked selection of features and insights twice a week.